The story of the submarine is fraught with danger and disaster. The introduction of this weapon into the Royal navy caused uproar because it was considered to be an underhand way of fighting. The first Holland submarines were superseded by the A class, of which thirteen were built. The record of these boats from the time of their launch, to the beginning of the First World War makes grim reading

The A1 was struck by the liner Berwick Castle in 1904 and sank with all hands. The A3 collided with her own depot ship and sank immediately. A4 was sunk at Devonport in 1905 when the wash of a passing ship flooded her ventilators, and the A5 was badly damaged by two petrol explosions also in 1905. The A7 (see sidebar) was sunk with all hands in Whitsands Bay in 1914, and the A9 foundered just outside Plymouth in1906 after being hit by the steam ship Coath. Luckily she managed to resurface and no one was hurt, but two years later petrol fumes killed four of her crew. These unsettling disasters had the effect of virtually halting the flow of submarine volunteers leading in some cases to men refusing to sail on what they thought were unsafe boats.

So we come to the A8, that already had a reputation for being unstable, sometimes diving without warning. On the morning of 8 June 1905 the A8 was on a routine training exercise in company with the A7 just outside the Plymouth Breakwater.

As was the routine in those days, the A8 ran with her conning tower hatch open whilst the crew prepared the submarine for diving. In those days submarines did not have hydro vanes to dive the boat, but relied on reducing their buoyancy, clapping on a bit of speed (8 to 10 knots) and putting the helm down. This had the effect of driving the boat underwater. The trouble was the buoyancy of the craft wasn’t very much in any case, so quite often the boats would dive weather the Captain wanted it to or not.

A nearby trawler, the Chanticleer, commanded by a Mr. Johns saw the A8 going along with its conning hatch open and four men standing on the submarines casing. Suddenly they were swept into the water as the A8 kicked up her stern and sank. The Chanticleer rushed towards the scene and picked up the four men who were Lt. Candy, the captain, Sub Lt. Murdoch, Petty Officer William Waller, and Acting Leading Seaman George Watt.

Tugs and divers raced to the scene and rescue operations quickly commenced. However an hour later these had to be stopped when two great underwater explosions rocked the submarine sending a huge spout of water ten feet into the air. From then on it was fairly obvious that all the rest of the crew had perished.

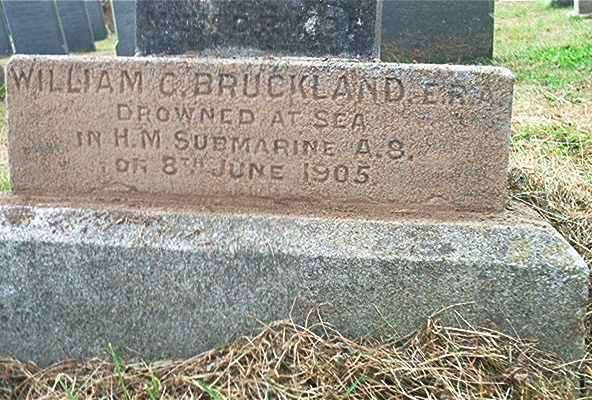

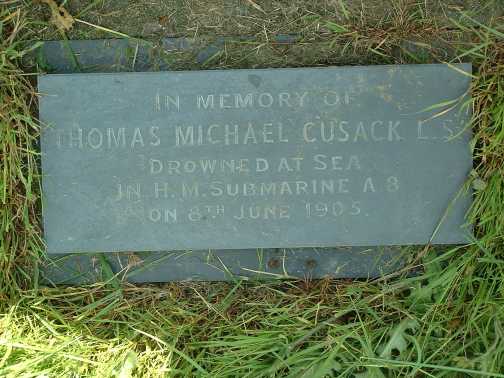

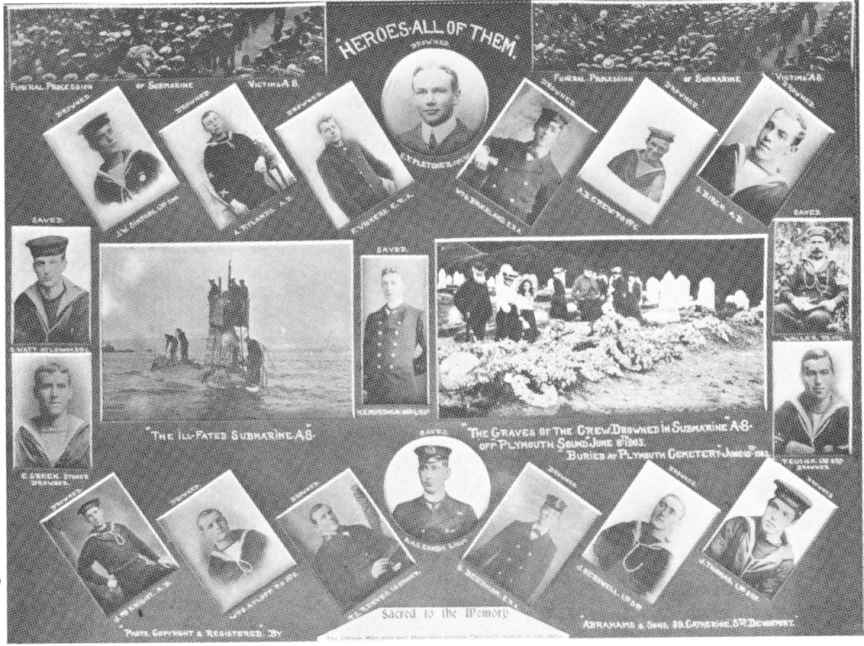

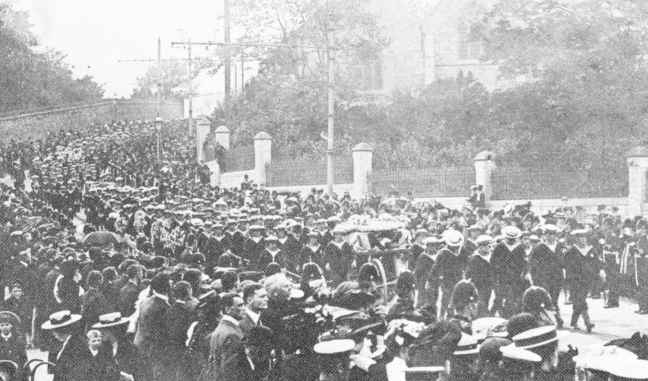

The A8 was subsequently raised and taken to Devonport Dockyard where the bodies of the crew were evacuated through a hole made by removing a metal plate from the hull. This metal plate was apparently later used to make a cross for the men’s’ funeral. The A8 was quickly repaired and was ready in time for the naval manoeuvres in 1906. It is hard now to explain the depth of grief that this tragic incident caused. The King sent a personal message to all the relatives, and the crews’ funeral procession took one and a half hours to cover the two miles from the Dockyard chapel to the Plymouth and Devonport Cemetery where they were to be interred. The crowds numbered in their thousands and thronged the entire route, in some places twenty deep.

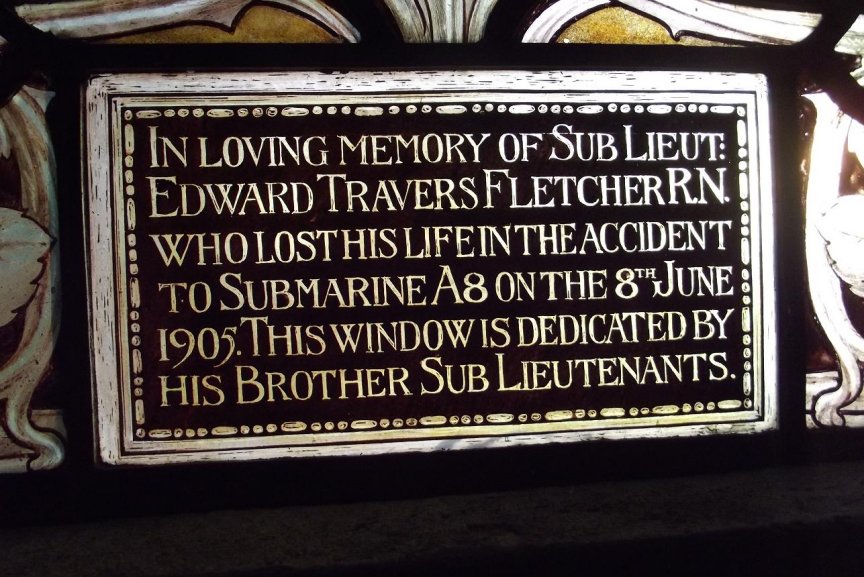

The funeral cortege was over half a mile long, with the dead sailors laid on gun carriages drawn along by naval ratings. The route was also lined by different Army regiments, and the crews from all the ships moored in the Sound in order to shown their respect and to keep the huge crowds from blocking the procession. Through out all this a band solemnly played Chopin’s Funeral March until the procession reached the chapel at the middle of the Cemetery. At about half past four in the afternoon, the final blessing having been said, the firing party discharged three volleys over the gravesite, and four buglers sounded the Last Post. Whilst most of the crew were laid to rest at the Plymouth and Devonport Cemetery Sub Lt. Fletcher was interred at his family home at Mallingford near Norwich. Leading Seaman John Kerswell was laid to rest at Crediton and E.R.A. Vickers was buried at Southsea.

Most of the graves are together, but are now sadly neglected, their broken crosses lying strewn upon the ground. The Trust that looks after the graveyard has made massive strides in clearing the place up, and there is some suggestion that the Royal Navy will pay to have the memorials repaired. I hope so. Last Poppy Day politicians and Service Chiefs droned on about how we should never forget. But we will, and in the case of these brave lads, we already have.

They deserve more than that.

2006: I am very glad to anounce that the graves of the A8 crew have recently been restored by the Royal Navy.This was in part brought about by the hard work and dedication of the trust that now runs the Cemetry. they have tidied up the place no end, and because of this many more people visit lookng for their relatives. Even so. well done the Navy.

I am very gratefull to David Barrett and his wife, for the information below and the photo’s. My wife and I enjoy looking around historic churches. Near us, at Marlingford, Norfolk, we found a stained glass window in St Mary’s church. It was erected as a memorial to Sub Lieut Fletcher, who perished in the A8 disaster. We knew nothing about it until we found the information on your site and another one. The Fletcher family resided at Marlingford Hall, near the church.

David Barrett says

Thanks for this information. My wife and I enjoy looking around historic churches. Near us, at Marlingford, Norfolk, we found a stained glass window in St Mary’s church. It was erected as a memorial to Sub Lieut Fletcher, who perished in the A8 disaster. We knew nothing about it until we found the information on your site and another one. The Fletcher family resided at Marlingford Hall, near the church. I have a picture of the window and inscription if you would like a copy. Best wishes, David.

Kim Hennessey-Hunt says

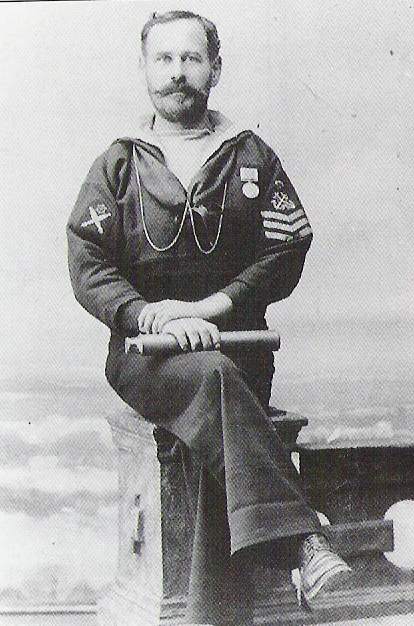

My Great Great Grandad was Richard Johns who part owned and commanded the Chanticleer. Apparently he was awarded a medal by the King. Do you happen to know what the medal may have been and do you know of any photographs of the Chanticleer? I would be greatful for any help you can offer.

Best regards

Kim HH

Geoff Sonley says

A distant relative was George Sonley, Chief Engineer on A8, who was one of crew that was drowned on 8.6.05. However, he is not mentioned amongst the deceased on any records that I’ve viewed. Any info would be most appreciated…….Geoff Sonley.

Alison Gunston says

Stephen birch was my paternal grandmothers brother and was 23 years old when he died on the A8 she described him as a wonderful boy.

In her memoirs she describes how her father was finishing a night shift as a porter and saw Stephen walk into the hotel with his kitbag as her father got up to greet his son he vanished. Later that morning they received a telegram to tell of the loss of the A8.

A devastating loss for a close family.

Chris Roche says

I would welcome being put in touch with Alison Gunston. Stephen Aaron Birch was my grandmothers youngest brother his father was Stephen Castle Birch who died in Canada. I have a photograph of Stephen seated on graduation from Holland 4. He was born down at Sellindge East Kent. Frederick Vickers grave at Hyland road cemetery Southsea is still unmarked if anyone wants to help me with that. Joseph Thomas is Buried in Brighton at the Bear Road Cemetery. For the record there were 4 military bands in the procession the Dorset`s played Flowers of the Forest which I hired a piper to play on the restoration of the graves for the 100th anniversary, his fee was a bottle of Jura single Malt. I have more in the family histories. I don’t believe George Sonley was among the A8 compliment on that day of the crew of 19, 15 of which died the crew list that day is known. Again I would welcome contact with Geoff Sonley.

Sue Escott (Weeks) says

I believe that my Dad’s uncle was Edmund Green who went down with the sub & Dad was named after him (Edmund Weeks).

Christine Green says

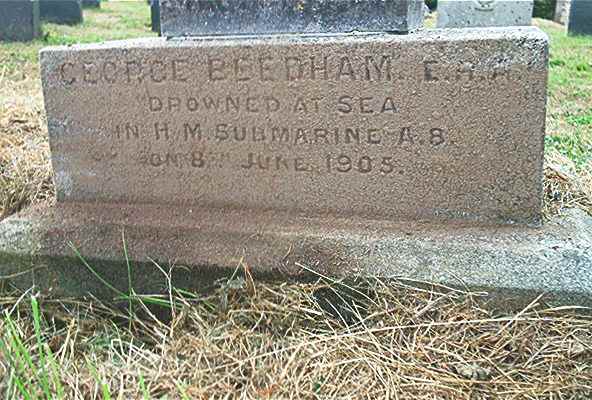

Thank you for this, my great uncle George Beedham was one who lost his life that day.

Garry Takle says

Thanks for sharing this article. My great grandfather was John Kerswell. I have visited his grave at Crediton church. The church warden was very helpful and indicated that over the years the grave has been visited numerous times. The headstone, with a very similar inscription to those photographed, is located in the middle of the graveyard and is well maintained. My great grandmother was widowed with a young son and pregnant with my great grandfather. I can only imagine the grief and hardship the tragedy caused. Our family remains closely tied to East Devon.

Alison Gunston says

Hi Chris,

I am sorry to hear of your dads passing.

It is a wonderful legacy he left of the history and photos relating to the A8.

It is something now that as relatives of

Stephen Birch we can pass the story and photos down to future generations of our family.

Thank you

Lisa Hailstone says

I first came across the A8 disaster whilst researching my family history – George Beedham was my 1st cousin x3 removed. Keen to know more, I visited the Devonport Cemetery and was very pleased to see the broken crosses restored and grass and hedges well manicured. The staff were incredibly helpful and described the 100 yr memorial service held in 2005. They also had a write up in the Cemetery guide. Many thanks for this web page – it all helps to build a vivid picture of the events in 1905 and what the crew, their families and the people of Plymouth went through.

Ps for Geoff Sonley. The Beedhams and Sonleys were related so could George Sonley and George Beedham be the same person?