Written by David Page

For many years my good friend and diving partner, Peter Mitchell and I, had been intrigued by the many “Myths and Legends”, circulating in the South West of England, concerning visits supposedly made to the region by Jesus, Joseph of Arimathea, Pontius Pilate, and their various retinues. Even the popular hymn “Jerusalem” asks the same question. The intention had always been to attempt to piece together that which we have been able to discover, from various sources, and for Peter to then “write it up” as one of his “Wreck Walks”.

Sadly, he passed away at the end of June 2015, so, as a “Tribute” to Peter, I shall attempt to put together the many notes we have made into something more “readable”, and hopefully spark off an interest in those others who read it.

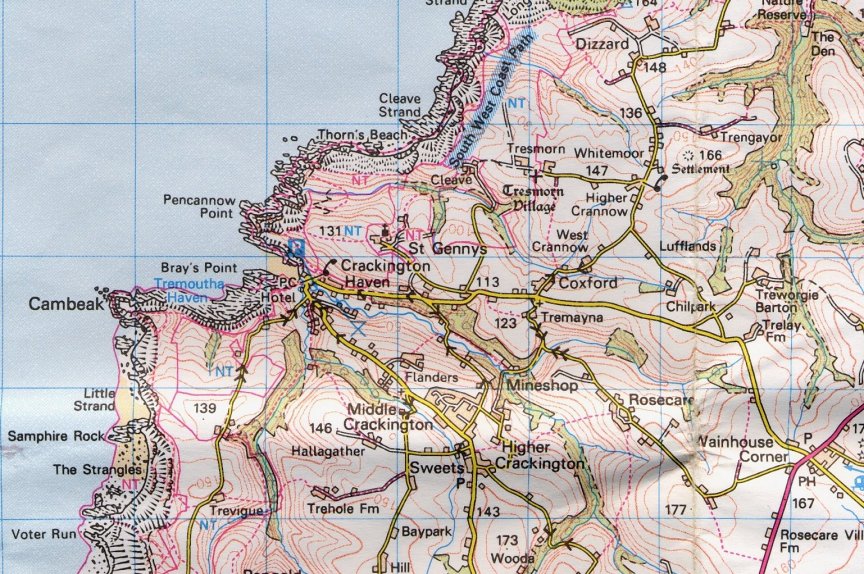

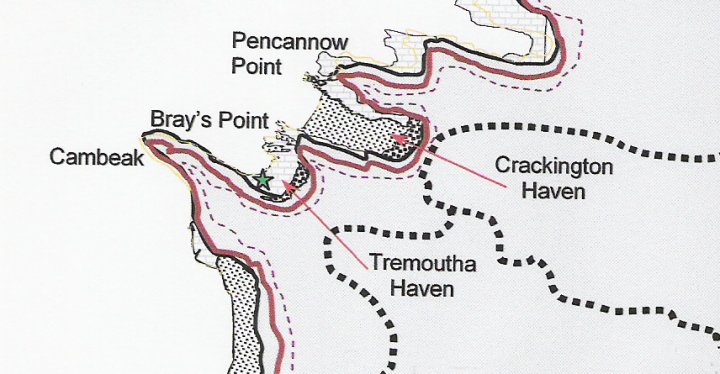

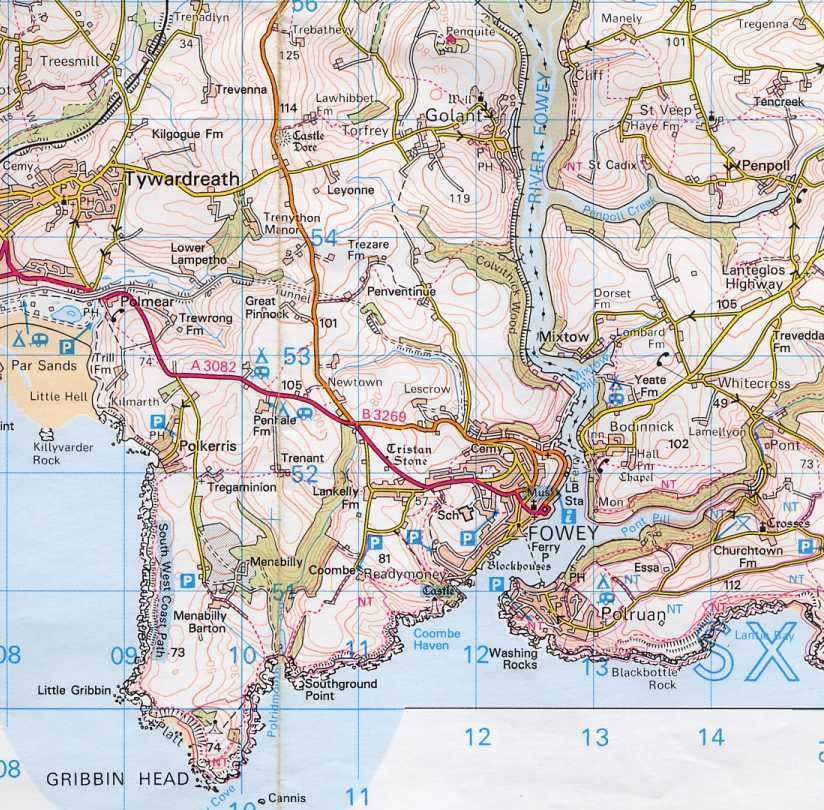

About 2006 or 2007 we were making passage down the coast of Southern Cornwall and decided to enter Fowey Harbour. On the headland to our right, beneath the ruins of St Saviours church at Polruan, was seen a large white cross. It is called “Punches Cross” and, so legend has it, is where “Jesus, Joseph of Arimithea, and Pontius Pilate and their retinues” are reputed to have landed whilst visiting their “Mining Interests” down here in Cornwall. Joseph was Jesus’ uncle and had been his guardian since Joseph of Nazareth had died.

There has supposedly been a “cross” here for many hundreds of years, and its true origins have been lost in the mists of time. It was this cross that ignited our interest, and had led us both into areas of research we had never before thought possible.

It was at first thought that “Punches Cross” was so named as a local attempt at saying “Pontius”. We soon found, however, that it was more than likely to be a “marker” to denote entry or exit from “Church owned” lands further upriver, and thus a “Toll” was payable to the local “Bishop” at Tywardreath, as pilgrims journeyed North and South between Ireland, Wales, and across the English Channel to various holy sites in France and Spain during early Medieval times.

But the Legends and Myths were many and widespread, and as they often contain a fairly large “Grain of Truth”, we both felt they were worth looking deeper into. We soon found out about “The Saints Way”, a path leading across country to the North Coast of Cornwall around the River Camel Estuary. Here are many more legends, and an ancient well, named “Jesus Well” is easily found on the “O.S. 1:25,000 Explorer Map 106” just North West of Rock at “SW 937764”.

Once again though, this pathway across Cornwall, Jesus’ well, and the many ancient churches found along the route, such as the one half mile west of “Jesus’ Well”, St Enodoc’s, were found to be more than likely a part of one of the many “Pilgrimage” routes across Cornwall that had developed from around 700 – 800 A.D.

We soon were confronted by “Conventional Archaeology” seeming to have no interest whatsoever in the subject, being intent instead on constructing whole “civilizations” on a piece of broken pot or discarded arrow head. It soon became apparent that no “formal investigations” had ever been carried out, nor were they ever likely to be so.

We therefore had to enter into some really “strange places” via the books we read, and the Internet searches we carried out. Some were quite plausible, even if our credibility was stretched at times !

The most interesting book by far, “The Missing Years of Jesus”, was written by an ex-policeman, Mr. Dennis Price. He had also looked at the many available books and articles, and had decided to investigate further. He had looked into the “Means, Motive, and Opportunity” as if it were a real Police investigation. It must be said that he has convinced me !!

To hopefully get a better understanding and insight into this matter, we must leave our present “modern” ideas behind. We must put aside our presumed “Historical knowledge” for the moment, as it now seems as if the history we have long been taught has been heavily “censored”, and only that which the “Church” wished to be known has been allowed.

We must start way back in history, around 8 – 7,000 B.C. at a time when civilisation was first developing in the “Tigris and Euphrates basin” in what is now modern day Iraq. The peoples there were the “Sumerians”, and later the “Babylonians”. These peoples soon expanded outwards into Egypt and Eastwards into India. They took their knowledge of the “sciences”, their civilizing ideals and their religions with them. The peoples of those areas they moved into were heavily influenced by them and their religions, and even today “Hinduism”, Buddhism, and the now almost extinct “Druidism”, reflects the reverence for nature held by the incoming culture into ancient Egypt.

It has long been accepted that “Phoenician, Early Greek, and Pre-Roman conquest” trading in Tin, Copper, Lead, and even Gold, had been carried out between the South West of England and the Mediterranean cultures for many hundreds of years, well back into the Bronze age.

What was not expected to find was that there had seemingly existed an earlier “Egyptian Trade” in those same commodities, and through the same area of Southern France around Marseille, and then Northwards up through the Rhone Valley to the land the Egyptians had called “Hyperborea” (literally the Land beyond the Celts – Britain).

The Celts were (and some still are) “Druidic”, through their contact with Egyptian traders, and the by now long altered religious ideas held by them. This contact soon spread across the English Channel into Britain. Major Druidic religious centres soon developed in Britain, notably at Avebury, Glastonbury, and Stonehenge. These places will figure once again as this narrative progresses.

Having now established a possible connection with Eastern Mediterranean culture and ideas, we can now move forward in time to when Jesus appears to be missing from the scriptures from when he was around 12 years old, to his re-appearance in them, 18 years later, when he was 30.

Judea, at that time was under “Roman occupation”, and they didn’t take too kindly to anyone questioning their pantheon of Gods. It is often stated in various scriptures that Jesus had an amazing intellect, and would often be found in various temples in deep discussion with many religious teachers. It is felt that it was around this time that he began to question, perhaps a bit too strongly, the current establishment and its leading figures. Bear in mind that he was not a “modern” young teenager, but a product of his time.

Moses, it must be remembered, had earlier led the “Israelites” out of Egypt, and had also had to deal with the “Worship” of the Golden Calf, the result being a set of rules by which we all should abide, “The Ten Commandments”.

What seems to be being ignored in many instances is that “Cattle” are held in esteem in many religions, most of which have evolved from the early Sumerian influence into ancient Egypt and other Mediterranean cultures. In light of this it can also be assumed that many of the other religious ideals, which would have eventually influenced the young Jesus, would have also travelled out of Egypt with Moses and the Israelites, mainly a reverence for nature and a “Love” for all mankind.

We can now try and connect the parts into what is, hopefully, a relevant story. Pontius Pilate, the local Roman governor of Judea, was a very wealthy man by the days standards, and had “Interests and connections” with many of the Tin, Copper, Gold and Lead mines in Pre-occupation Britain. The earlier unsuccessful “Roman” invasion attempt by Julius Ceasar in 55 – 54 B.C. had resulted in many trading connections being made between the then continental Roman Empire and Britain, and Pontius Pilate had taken full advantage of them.

Joseph of Arimathea was also a very wealthy man, as well as being high up in the Jewish Sanhedrin, the local Jewish Governing body, and in charge of Trading and Mining interests alongside Pontius Pilate. He had also been made guardian of Jesus by virtue of being his uncle, Mary’s brother.

It therefore seems natural for him and Pontius Pilate to visit those interests and, given who they were, they would have both had large retinues with them. This would have all been well before the finally successful “Roman” invasion of Britain by Claudius, and the later expansion carried out by Vespasian in 43 A.D.

It is felt that Pontius Pilate tipped his friend and business partner, Joseph, off over Jesus’ growing adverse impact he was having in Judean religious circles, and advised the family to flee to Egypt. It would have been here, if he hadn’t already heard of it, that Jesus learnt of the far off land that had not only held off the supposedly invincible Roman Army 60 odd years earlier, but also that its peoples had very similar spiritual ideals and beliefs as his own.

What teenager could resist a visit to such a place, and this is where Dennis Price’s book “The Missing Years of Jesus” and his use of “Means, Motive and Opportunity” becomes so believable.

Means:- Yes, he certainly had the means to visit Britain. His uncle Joseph was well placed within the Judean regional government, had a close financial and personal contact with the local Roman Governor, “Pontius Pilate”, and was also part of the Roman controlling body in charge of mines and mineral extraction.

With this in mind, Joseph would have had access to shipping and transport to anywhere within the then known “Roman world”, and would have had firm contacts with traders beyond it. Jesus’ father, Joseph of Nazareth, had for some reason disappeared from mention in the scriptures, and had been assumed to have already have died.

Joseph of Arimathea, being Jesus’ uncle, would have therefore taken on a role as the young Jesus’ guardian, and thus it is only natural that he would have taken the 12 year old Jesus along with him on any visits to the many mines he had an interest in. Along with Jesus, he would also have taken a large retinue of Clerks, Slaves, and possibly even other family members, such as his sister Mary, Jesus’ mother, given his governmental status.

Given the involvement of “Pontius Pilate”, and the quite probably large retinue he also would have had with him, we can now see that this would certainly not have been a “small group on a weekend visit”, and the memory of it would certainly have passed into record of some sort, even if only as a set of “Legends and Myths”.

Motivation:- As has often been stated in the scriptures, Jesus, as a youngster, had an exceptional intellect and was often to be found in discussions with religious leaders and scholars in his local temples. Through these he would have undoubtedly heard of the stories of the Island peoples on the edge of the then known “Roman” world who had, 60 -70 odd years previously, successfully thwarted 2 invasion attempts by the supposedly “invincible” Roman Army.

There was already a “resistance movement” amongst the population of Judea to the occupying Roman Army, and the chance to “rebel” is a potent force for a young and very receptive mind. He would have understood that “military action” was a non-starter, but to alter the religious mind-set of the Romans pagan beliefs from within, and even that of the ruling Jewish “Pharisees” ? Now that would have been a different matter completely.

He would have heard of the “Druids” of that land and their similar “monotheistic” beliefs as those held by his own people. He would also have heard of “Stonehenge” and it’s design similarities with the “Labyrinth” under the Greek temple at Knossos.

He would have heard of the stories of the Minotaur, half man and half bull who lived in that Labyrinth, and would have been told of the “Bull” worship that had its origins in Greek and even earlier Egyptian religions. A reflection of this “Bull” worship can still be seen in the “Hindu” religion of India, and the reverence placed on all living things amongst “Buddhists”

The connection would then have been easily made, in his mind, when told of a similar belief in, and sacrifice of, “White Oxen” by the Druids at Stonehenge, along with their worship of the “natural world”. Many of our present religious celebrations have been developed from earlier Druid beliefs, and the stories of the “Green Man”, and the habit of “Touching wood” for good luck being with us to this day.!. What young lad, soon to become a teenager, could resist the chance of travelling to such a remote and mystical land, and to learn from, and be educated by, the people living there ?

Opportunity:- These must have been many, given his uncles status, but it would seem that the largest incentive would have been when Joseph was forced to flee with his family to “Egypt”. As this region was also under Roman control at the time, and so therefore also under local Judean overview, it was not a place of complete safety, even if their religious views were, by now, similar to his own.

It is more than likely that this was the spur leading to the family coming to Britain, for Joseph to be in close touch with his mining and trading interests, and for Jesus to study under, and to eventually live amongst, the similarly minded Druids at the great religious centres of Glastonbury and Avebury. The site of Stonehenge is only 30 miles to the east, a good days walk, and it is inconceivable that he did not visit the place and learn of its mysteries during his reputed 18 years living here.

The “Druids” were renowned for their skills at “Oratory and argument”, and their “priests” were known to have walked without fear between warring factions and to have calmed down serious situations, a skill that Jesus is often stated to have put to use in his later ministry.

This book by Dennis Price is, as stated before, a very compelling read and would go a long way in convincing one that Jesus did really spend his “Missing Years” here in Britain before returning to Judea with his ideas fully formed.

To the ruling religious leaders of Judea he would have been looked on as a major “trouble maker”, a certainly unwanted “voice of the people”, and they would have tried to minimise his influence as much as possible. His teachings in the 3 years after his return certainly did not sit well with them. Jesus finally forced their hand with his return to Jerusalem during “Passover” and his disruption of the temple money-lenders. He was arrested and sentenced to death.

Now the strange part of this is that the “normal” method of execution, for the perceived crimes he had carried out against the ruling classes and religious leaders, would have been “stoning to death”, a method reserved for petty criminals and women, and would probably have resulted in his lifetimes teachings, and manner of death, being completely forgotten about in a matter of days.

To really make his voice and teachings echo down the centuries to follow, he had to “Martyr” himself and to be killed by his own people in the most horrendous manner available,-“Crucifixion”. Jesus had chosen his place and moment well. Jerusalem during “Passover” was then, as it is still now, a place of considerable “tension”, and the occupying Romans had to take great care that these “tensions” did not escalate into major rioting.

This probably goes a long way in explaining why “Pontius Pilate” who, as outlined above, knew Jesus during his youth, and who more than likely still had mining and other business dealings with Jesus’ Uncle, “Joseph of Arimathea”, refused to take any part whatsoever in his conviction and subsequent execution and, basically, “washed his hands” of the whole affair.

This would therefore ensure Jesus’ terrible death at the hands of his own people, the memory of his killing being retained for centuries down to the present day, and the start of one of the worlds major religions.

Hopefully, one day, a proper “Forensic examination” of all existing subject matter will be undertaken but, until that takes place, and unlikely as that examination will be, given the power of censorship still wielded by the “Roman Catholic” church, we are stuck with what we have at present.

There are probably many other “Internet searches” and books available for research into this subject but, given the 2000 year time scale involved, much will now be obscured by Legend, Folklore, and Myth, as well as the obvious resistance in peoples minds to altering their whole historical perception. This is a very intriguing subject though, and it could occupy ones time in searching for years to come, even if it is doubtful that a definitive answer could ever be reached !!

My friend Peter would have loved to have been able to put this story into his own words, but sadly he was unable to. I hope therefore that my “precis” of the copious notes we had collected have done the job for him. Only he will now know whether there is any truth in all the Legends and Myths, or whether they will forever remain just that – “Legends and Myths”.

You, the reader, however, can form your own opinion as you follow in our footsteps, and those of the many thousands of “Pilgrims” who have journeyed along “The Saints Way”, and have been captured by the story and think to yourself – “I wonder” !!!

“R.I.P. Peter”.

David Page,

July 2015.