When I was a child some of my favourite stories were about the great Australian grain races, and the Tea Clippers sailing across the oceans from China. The photographs and drawings of these huge sailing ships fascinated me, and no doubt countless others, because today, ‘Tall Ships’, as they are now called, draw enthusiastic crowds in much the same way that steam trains do. People nowadays put this crowd pulling down to nostalgia, but even in their heyday these massive sailing ships with their graceful lines and billowing sails drew even bigger crowds, and many had songs and stories woven around their legendary voyages.

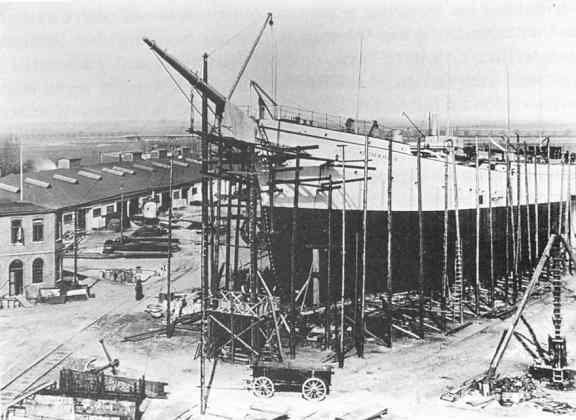

Probably the very last of these ships to be wrecked on the south coast of England was the Herzogin Cecilie, or as she was more affectionately known, the Duchess. She was a four masted steel barque built by Rickmers of Bremerhaven in 1902 as a school ship for the North German Lloyd Line, and was 314 feet long with a gross tonnage of 3242 tons. When the Great War started the Herzogin Cecilie was interned in Chile for the duration, and afterwards she was allocated to France by the War Reparations Board. The Germans tried to repurchase her but were turned down flat, and eventually she passed into Finnish ownership, being bought and commanded by Captain Gustaf Erickson of Mariehamn. Under his ownership the Herzogin Cecilie carried cargo’s all over the world, but it was the Australian Grain Races that made her famous, winning eight of them in succession.

In 1936 the ‘Duchess’ started what was to be her last voyage and her last Grain Race. From Port Lincon in Australia to Falmouth took her just 86 days, comfortable beating her nearest rival, the Pommern, by seven whole days. Her orders at Falmouth were to proceed to Ipswich to discharge her cargo of grain, but two days later, early on the morning of the 25 January, in thick fog and rough seas the Herzogin Cecilie struck the Hamstone just a few miles from Salcombe. Holed in the forpeak, the ship pounded fiercely then settled by her head with her well decks awash.

When dawn broke just about everybody and his aunt had turned up to view the wreck, and quite a lot thought that they should also go on board. This considerable hampered the rescue operation, but in the end the Salcombe lifeboat took off twenty-two of the crew, leaving just the Captain, his wife, and six crewmembers. A breeches buoy was rigged up to take off all the luggage and personal belongings, but most of this was quickly stolen when it landed by members of the public, who had by now degenerated into something of a mob.

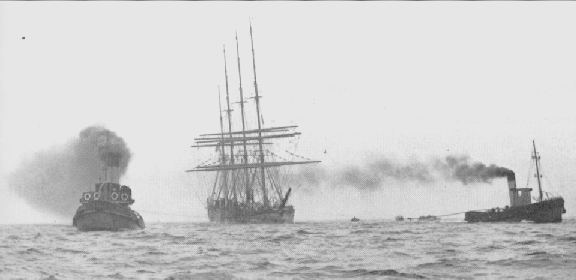

For seven weeks the Herzogin Cecilie lay stranded on the Hamstone whilst her four and a half thousand tons of grain rotted and fermented. The stench was appalling and fears of it polluting the beaches around Salcombe kept the owner and the local council arguing fit to bust. Every day huge crowds gathered to view the ‘Duchess’ and local farmers made a fortune charging people to cross their land for a better look. Eventually the grain became so swollen that it started to crack the decks, and this seemed to galvanise the salvage attempts. By 7 June enough of her rotting cargo had been removed to allow the installation of powerful pumps, and on each high tide tugs repeatedly attempted to pull her off. At first it looked as if the ‘Duchess’ was stuck fast, but finally, on 19 June the Herzogin Cecilie floated clear of the Hamstone. The local council still would not let her be towed into Salcombe, fearing all manner of disease, so in the end the ‘Duchess’ was beached in Starhole Bay just at the entrance to the harbour. Unfortunately what appeared to be a ‘safe’ sandy bottom, concealed rocks, and in the July gales she broke her back and her masts soon tumbled down into the sea. It was the beginning of the end. Ironically, if the Salcombe authorities had allowed her into harbour she would have been saved unloaded and on her way long before the gales came. As it was the thing that the council feared most happened. The grain washed out of the wreck and fetched up on all the beaches. However it didn’t cause any pollution because the seagulls eat most of it, and the rest got washed away. So much for the experts.

In the ensuing months all the fittings were stripped from the wreck, the beautiful figurehead sent to a museum in Finland, and the remains sold to a local scrap merchant for the princely sum of £225. A sorry end for a marvellous ship.

Today at low tide, the remains of the ‘Duchess’ just about show. In the summer there is always a buoy attached to the wreck, (at the bows) and it is prominently marked on all the carts, so you really cannot miss it. Still if you do, just ask. Everybody knows about her, and most will be glad to point her out. The wreckage lies in less than 25 feet of water on a sandy bottom, and I had been told that there was just a jumble of iron plates, and that the wreck was hardly worth diving on. Not so. The Herzogin Cecilie must be one of the prettiest wreck sites going. Part of the bows is angled over to form a sort of cave into which you can easily swim to play with the many wrasse that lurk there. Stray light twinkles in from various small jagged holes backlighting the interior with a soft glow. Marvellous for underwater photography. There is a huge amount of iron plating and decking lying across the sand and also pushed down into the sand. There is still quite a lot of material from which the sails were made buried in the sand, but what I really like about this wreck are the tunnels. Various parts of the deck and hull have fallen down in such a way as to make iron tunnels along the sand. They are not really that long and you can usually see to the end, but they are a bit special. In the tunnels, the seaweed catches the light and the current as it wafts in and out of the ragged openings, along with a myriad of small fish. It really is most enjoyable, and on one dive we all spent at least twenty minutes just swimming in and out of these tunnels. The rest of the wreck stretches out along the bay, and it is still possible to find wooden decking, and the iron pulleys that once held the ropes that hoisted up the great sails.

It’s a great jigsaw of a wreck, and you can either put it together, or just poke and prod about. The Herzogin Cecilie will always be remembered as one of the great square riggers, but it is as a wreck that she really lives up to her old nickname, the ‘Duchess’ a real charmer.

This book tells you all about the Wreck, click the image to learn more