I am very gratefull to Les Smale B.E.M. for this fascinating account of his part in the battle of Narvik, where he survived the sinking of H.M.S.Hardy. His account is also quite unique, because he wrote it all down so soon after the event.

I will, while the events are still alive in my memory, attempt to give a description of events which brought me to take part in the Battle of Narvik.

The Hardy left Scapa Flow on the evening of April 2nd, together with the remainder of her division bound for the Shetlands. A little after we had left the boom defences, the air raid defences of Scapa opened up on the dozen or so raiders who were darting around in the almost dusk. A heavier barrage I have never seen. The sky literally had Black Measles. This was our first raid and quite naturally we were all anxious to have a crack at them, but with all our beckoning we couldn’t persuade them to come near enough to open fire. On the whole, I guess we were quite a bit disappointed, still, though we did not then know it, our chance was to come, and soon.

Though cold, it was quite calm when we arrived at Sullam Voe (Shetlands) the next morning and after oiling with the Hunter alongside us we went to anchor. It was now the 3rd. Of April and no one seemed to know exactly why we were there or for that matter, where we were going. However Captain (D) was not slow to take advantage of the lovely weather and the time to exercise General Drill to the utmost. Action Stations, Landing Parties, were exercised even to the extent of Hotspur flying a Swastika.

During the Friday evening of the 5th, four of the ‘I’ class destroyers arrived well loaded with mines, following which came all kinds of rumour as to where we were to escort these minelayers. Well, next morning at 0400 hours, we weighed anchor and put to sea and at about eight ‘o’ clock we rendezvoused with the Battle Cruiser H.M.S. Renown. Soon, we were all settled down in our allotted positions and took a course something East of North. The sea was very heavy and so was the rain and by the next morning one couldn’t help but feel the extra nip in the air. This being Sunday, we had, as usual, a little service on the messdeck, after which Lower Deck was cleared and the Captain, (Warburton- Lee) disclosed that during the afternoon we were crossing the Artic Circle, to which he dryly commented that this called for the same procedure as for ‘crossing the Line’ Our final destination, he said, was a little south of Narvik where we were to lay mines at dawn on Monday morning. Off Hoveden 67

All through that day the sea was still quite high and it was not until during the night that it began to ease down, and only then because we were getting near land. Dawn of Monday the 8th broke with us at action stations and violating Norwegian neutrality. The mines were all laid within half an hour of the planned time, so despite the weather we had done our first real job well. All that remained for us to do now was to patrol the minefield and guide Norwegian fishermen around it and capture any German ships trying to pass down trough neutral waters which they had previously been doing.

The weather here in the Fiord, was beautiful, hardly a ripple on the water and everything surrounding us covered in a white blanket of snow. Well, here we stopped until just after noon when there came a message from the ‘Gloworm’ (Destroyer) that she was being attacked by two enemy ships and was returning their fire. Then all was quiet and nothing more was heard of her.

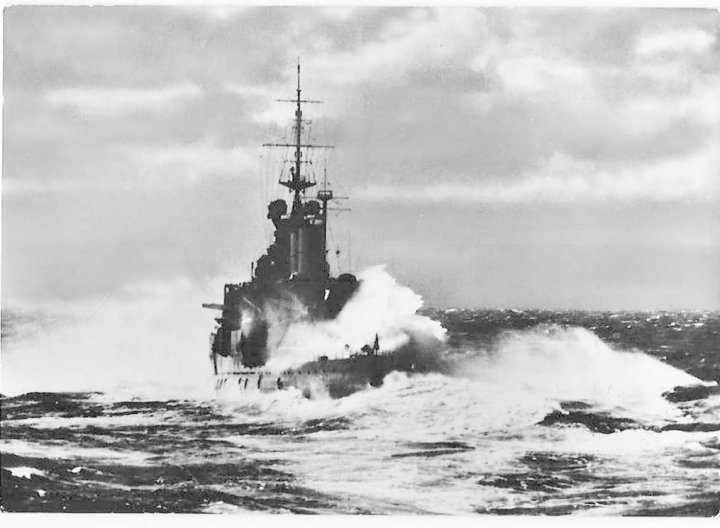

Meanwhile, word came for us to join ‘Renown’ and off we went at full speed. The German Fleet was at sea and Blenheims, Hudsons, and all sorts of our bombers were out looking for them in an effort to bomb them. Things were warming up and everyone, though they knew well what the consequences may be, was rather glad. Things were moving rapidly and it was not many hours before we learnt that the German Fleet was moving northwards. Just after 1700 that evening we met the ‘Renown’ who in the meantime had joined up with our minelaying friends of this morning. The sea was now extremely rough and so, for the night, we took up a formation of line ahead. ‘Renown’ leading with ‘Hunter’, ‘Havock’, ‘Hotspur’, and the minelayers following.

At dawn the next day as was usual, we went to action stations. There were snowstorms about and it was still very cold. We must be further North than ever. We were going through the usual procedure when suddenly, without any signal , the ‘Renown’ altered course to Port. Quite naturally all our bridge staff turned their binoculars in that direction. They need not have done, for a snowstorm suddenly fell on us and blacked, or rather whited everything out. The ‘Renown’ then relieved our anxiety by signalling with their big light ‘Two Enemy’. I suppose nobody could express their feelings at that moment. Mine were, I think, a mixture of excitement and expectancy. Wondering if it really was the enemy and what it would be like to be under fire. We were soon to know for in a moment or two the ‘Renown’ opened fire with a broadside of 15inch guns at the leading ship of the two.

The snow had cleared and we could now see them away on the horizon. We, that is the ‘Hardy’ and ‘Hunter’, opened fire at extreme range on the second ship. There was a honest to good fight for perhaps a quarter of an hour and during that time we realised that the leading ship of the enemy was a cruiser of the ‘Hipper’ class and the other, engaged by just two tiny destroyers was none other than the ‘Scharnhorst’. There were splashes all round us but almost everybody was too busy with their own job to let that worry him. They got a straddle on us and while I was thinking that the next one would ‘see us off’, it never came. It appeared that they were concentrating on the ‘Renown’. There were several good straddles on her and we seemed to be left out of it. Then they, the enemy, turned, not towards us, but away from us, and the speed in such big sea’s as we pursued, was too much for the destroyers to maintain. Several times it seemed that we would break our back, so we had to ease down to about twelve knots. ‘Renown’ was still chasing them and as we went along we passed all kinds of wreckage from an obviously German rubber raft and pole attached, to a Marines’ cap. By now the enemy was out of sight and as ‘Renown’ went over the horizon she signalled us to return to our patrol on the mines. By this time we heard that the Germans had invaded Norway and at last we knew why their fleet had put to sea. On our way back we learned that we had suffered no casualties or damage, except that there was seven to eight inches of water in the foredeck mess deck, and everything movable, had moved, and practically all of it had broken.

During the lull on the way back we replenished the ready use ammunition lockers and ‘squared off’ the ship generally. The Captain and Gunnery officer were full of praise for the way the men behaved and the ship was full of talk of what, probably, was the most exciting moments of our lives. It was certainly my most exciting moment up till then.

Instead of returning to our patrol as ordered by ‘Renown’, we went, due I suppose, to signals from the Admiralty, further North towards Narvik with the Lofoten Islands on our Port and Norway to Starboard. Then came more coded messages from the Admiralty, and in consequence I was amongst those detailed from each ship for ‘Landing Party’. We all got rigged out and set about writing farewell letters in case we did not return. Not knowing how long we may be ashore, we all fairly well packed ourselves in with chocolate and cigarettes. The plan apparently was to bombard the harbour and shore batteries of Narvik and then land and take the place over. This idea was quashed however, when a couple of hours later we called at a pilot station some forty miles south of Narvik. Here we learnt that we were up against a superior force, and to put it in the words of the Pilot ‘ I wouldn’t go in with a force three times as big as yours’. Plans were changed and D2 ( Captain Warburton-Lee ) decided on a dawn attack. Plans were drawn up and method of attack signalled to all ships concerned.

That evening when we closed up for a final check over of instruments, the alarm bells rang and away we went after what looked like a destroyer. As we neared, it turned away but we soon overhauled it to find that it was a small fishing boat. That night…. it was now the 9th of April, we continued a patrol of the Fiord and at about midnight with everyone at action stations the five ships, the ‘Hostile’ had joined us during the evening , began to move towards Narvik. My particular Action Station was as a member of the Gun Directors crew with a duty to operate the Cross Level Unit. This unit, using the distant horizon as datum, measured the angle of ship movement at right angles to the line of fire and fed in an appropriate line correction. Since the close proximity of the fiord shoreline on either side made the unit inoperable I was ordered out of the Director to become a Bridge messenger and as such was in a ringside seat as it were to see all the action that was to come. The orders were to sink all ship targets, and needless to say everybody was ‘on their toes’ the whole of the time. It began to snow pretty heavily and we could see neither shore, and this made navigation that much more difficult. The ‘Asdic’ submarine detection gear was used to get echoes from either side of the fiord so that we were able to continue our progress up towards Narvik. It was bitterly cold, and where we were moving around in a vain effort to keep warm, we were forming circles of ice on the deck. Twice, rum and tea were brought around and did we need it. Generally a quiet atmosphere surrounded the ship as was only to be expected in such a tense situation. Once, in particular, when the Gunnery Officer, Lt. Clarke, passed around that we were about to pass a shore battery, everything was particularly quiet, with no one saying a word and only the wash of the ship to stir the apparent ‘peace’.

Just about 0400, it was now the morning of the 10th April, in the vicinity of the harbour we made for what we thought was the entrance and only stopped just in time when we realized that it wasn’t. After a little scout around we eventually found it and as the plan had been to fire on the enemy from the entrance we were all very surprised when the ‘Hardy’ began to lead the division into the harbour itself. It seemed to be so cheeky and yet here we were doing it. There was already one ship run ashore on our Starboard side as we went in, but there were still plenty more good ones about for us to sink.

Merchant ships were ‘small fry’ at the moment. We were looking for destroyers and a submarine. All our guns had been unfrozen with hot oil on the way up and were loaded ready for anything. Everything seemed to be still very quiet and peaceful, but that was all changed a few minutes later when we suddenly sighted a destroyer’s bows showing from behind a whaling factory ship. Torpedoes were fired and I guess at least a couple of them found their mark for there was a terrific explosion together with a vivid semi circular white flash of stars twinkling around the edge. If one could forget what that explosion contained it could be described as extremely beautiful, but when one thinks of sleeping men being killed outright, then it is different, perhaps that’s not the case with a German even if they are the enemy. Simultaneously with the explosion we gathered speed and opened fire with the guns. Turning to go out of the harbour, two more destroyer’s were sighted to Starboard and engaged, but being probably still asleep, they didn’t at this moment return our fire.

By now the ‘Hardy’ was out of the harbour with the remainder of the division following around in their turn. A second attack was planned and when some ten minutes later we re-entered the harbour they were ready for us. I should say, some of them were, for some were firing High angle shells and others Low angle shells. The Germans didn’t seem to know if they were under surface, or air attack. It was a crazy sight which greeted us this time around, with stems, sterns, funnels and masts sticking up all over the harbour marking the graveyard of the ships sunk in the first attack. But for the grimness of the situation, it was almost an amusing sight. There was more gunfire from what appeared to be shore batteries, and they were firing ammunition fitted with tracer so that you could see it coming towards you. Sometimes it exploded in flight, while at others it went off on contact with the water. Glancing over the ship’s side I noticed that there were explosions erupting from the water at various places around the ship which threw up black clouds of smoke. I thought they might be controlled mines but I don’t know for sure. We came out of the harbour again without casualties but with a well earned scar, a two inch hole in the foremost funnel.

We were all quite happy and very pleased with our work but when the Captain ordered yet another attack we were not quite so keen. It was getting very ‘hot’ in the harbour and they were ready for us this time. But if the Captain went, we went. For the third time we entered the harbour and they were more than ready, for we were greeted well and truly with very heavy gunfire and what seemed to be dozens of ‘tinfish’ (torpedoes). After seeing the effect of our own torpedoes, I know there was no one anxious to see the effect of one of theirs on us. Each time one came for us, full speed ahead was ordered and we turned toward it to present as small a target as possible. On one occasion we had just evaded one, only to run into the path of another and I honestly believe that my heart stopped beating as I held my breath, together with everybody else, as we waited for the explosion to occur. But it never came, despite the fact that it passed right under us and the general belief that German torpedoes were all fitted with magnetic heads. If he does, then we owe our lives to our D.C. gear, a device which neutralises the magnetic field inherent in a ship.

With that thrill over, two of our foes burning and the shore batteries silenced, we turned from the harbour for the last time. The wreckage in the harbour would have to be seen to be believed, so I can make no attempt to describe it adequately, other than to say that it was immense.

As we passed the harbour entrance with our guns facing aft and firing a few farewell shots we all felt to a certain extent relieved, but when all of a sudden, ‘Alarm bearing Red 5 degrees’ was ordered we were all taken by surprise. There was no need to look, for we knew in a moment that we had met the enemy once more and to his advantage. He must have been waiting for us, for in an instant shells were crashing into us. I found myself at the bottom of the ladder behind the wheelhouse and was thrown flat on the deck by a shell which blew off the steel door on the Port side. Fragments of this door or shell injured the two signalmen who were there with me. I put them into the Navigator’s cabin and dived into the Captain’s cabin on the Starboard side myself. Another salvo crashed in and something hit my head but I wasn’t hurt. Self preservation, I guess, took me to the Port side, but just as I got there the telegraphs man came out of the wheelhouse shouting that the Cox’n was dead. I, for no reason I can explain, went into the wheelhouse and took over the wheel from Lt. Stanning, the Paymaster, who said he was going back to the bridge. The wheelhouse was a shambles. It was not till I was actually on the job that I realized the danger I was in, but I consoled myself by thinking that ‘if this was my day, then it was my day’. I felt better. I couldn’t make contact with the Bridge and my repeated calls through the voice-pipe of ‘Wheelhouse.. Bridge’ were unanswered. I was left to my own initiative as to what I should do. Looking through the gaping shell holes in the wheelhouse side, I could see for the first time the German ships. There were five of them, two now ahead and three to Starboard.

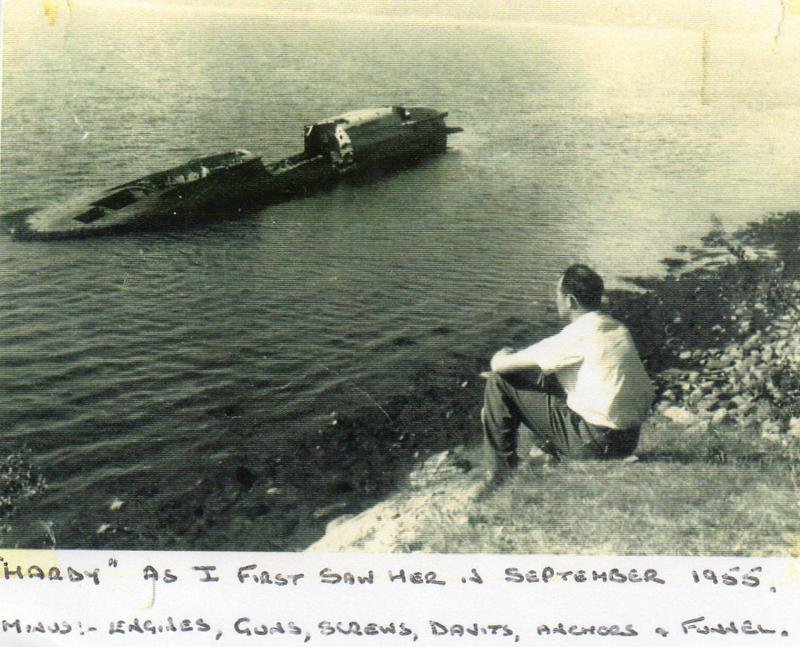

We were close to the shore, so I steered a course that kept us as close as I dared and hoped we wouldn’t go aground. In a little while contact was made with Lt. Stanning on the Bridge and he ordered ‘Hard a Starboard’, we’re going to ram. I felt fit for anything now, but almost immediately it was cancelled by ‘Hard a Port’ we’re going ashore. I put the helm over to Port. Just as we were about to ground the Midshipman came into the wheelhouse shouting ‘your going aground, your going aground and rang the engine telegraphs to full astern. It had no effect as the engines had lost steam due to a hit in the boilers, and it was because of this loss of power that Lt. Stanning had changed from ramming the enemy ships, to taking the ‘Hardy’ ashore. I didn’t feel the ship ground and I think I stood there at the wheel in a dazed condition for two or three minutes until someone came by shouting ‘Abandon Ship’. I walked, they were not firing at us now, out onto the point five, machine gun deck, and helped the two previously mentioned injured signalmen into the seaboat. The whaler was full to overflowing with no one at the falls to lower it. Someone did come along to perform this duty and took a turn for lowering as for a normal boats crew of seven, whereupon the boat went down with a terrific rush and capsized. A Carley Float was in the water, by now full of survivors, and I remember shouts of ‘anyone got a knife. None was forth- coming, it was needed to cut the paddles free. Some men were beginning to reach the beach and I noticed that the swimming distance was not all that far and that one could wade half the journey.

Being a fair swimmer I decided I could stay and help where I could, so I took off my duffle coat and oilskins and went to the bridge to give a hand as necessary. The Bridge was in a terrible state with the following casualties. The Captain seriously wounded in the head, arm, and unconscious. The Signal Officer and Gunnery officer dead, the Navigator suffering from concussion, and the Paymaster with a foot injury. I, with the Middy released the Telegraphist from his remote control post, the door of which was jammed shut. We then assisted the Doctor to bandage the Captain and then put him into a Neil Robinson stretcher ( a sort of wrap around affair to prevent the patient falling out) and lowered him to the Foc’sle deck. We got the Navigator clear of the Bridge and destroyed what books we thought might be of use to the enemy before finally leaving the Bridge ourselves. Meanwhile, No 4 gun had been getting up more ammunition and was again firing at the enemy. As I reached the Foc’sle deck and had just taken up my coat to retrieve my valuables from the pockets, the Germans opened fire on us again and registered a direct hit on No. 2 gun which was already out of action. I dropped flat and felt splinters of metal hitting my tin hat, which undoubtedly saved me from injury.

The Doctor was injured in this, and the Chief Stoker mortally wounded. Having retrieved my valuables we put the Captain in his stretcher over the side and into the water. Our only access to the water at this point was via the whaler’s falls which still hung vertically from the davit head. Shinning down, I paused on the lower block to take of my fur lined flying boots before entering the water. I didn’t get them off as the First Lieut. Came down the fall on top of me and I found myself in the water. One of the signalmen who had been injured behind the wheelhouse was still in the water and asked me to help him. I saw him ashore alright and then began to realize the cold was colder than I had ever experienced before. By now No.4 gun had finished firing but the Germans were still firing at us and bits and pieces came flying over making us continually have to duck under the water in order to dodge the danger. The First Lieutenant was now calling for help with the Chief Stoker, so I went to give him a hand ashore. I then went back to assist the Gunner (Mr. McCracken) to bring the Captain to the beach, where almost immediately he died. I daresay he would have been happier had he known anything about it, if we had left him on board.

My first wish now was to get the circulation going again, so I stamped my way up through the snow to the nearest house, as had so many others of our crew. Looking back, as I left the beach, I saw a ship upturned showing keel ,rudder and propellers and felt that it must be one of the German destroyers that we had sunk. Unfortunately it turned out to be the ‘Hunter’ though I didn’t know it at the time. Our own ship was on fire forward, and rounds of ammunition of different calibres were exploding all the time. I eventually reached the wooden house and there were two women there, a Mrs. Christianson and her daughter, doing all they could to make the survivors comfortable. The house was full of steam from thawing bodies. Personally I was so cold and so exhausted that I could not take my soaking clothes off, though I knew I had to. A Yeoman of Signals helped me out of them eventually, and I wrapped myself in a black silk dress which I found on the floor. I was glad now that I had been unable to discard my boots at the bottom of the whalers fall when leaving the ship, for unlike most of the others I still had something to wear on my feet. Many made improvised shoes by cutting their rubber lifebelts and putting their feet in the sealed ends. The most comical of all I think, was our Canteen manager who wrapped his legs around with newspaper. Then there was one who cut a hole in a carpet, put his head through it and tied the two draping ends around his body with a piece of string. While I was still getting warm our Torpedo officer called for volunteers to go back to the ship to get a man seen walking on the Quarter deck. They went, four of them, in a Carley float and brought back the Navigator, for it was him, still in a concussed state. These four men were awarded the D.S.M. and well deserved in view of the danger from exploding ammunition from the fire still on board.

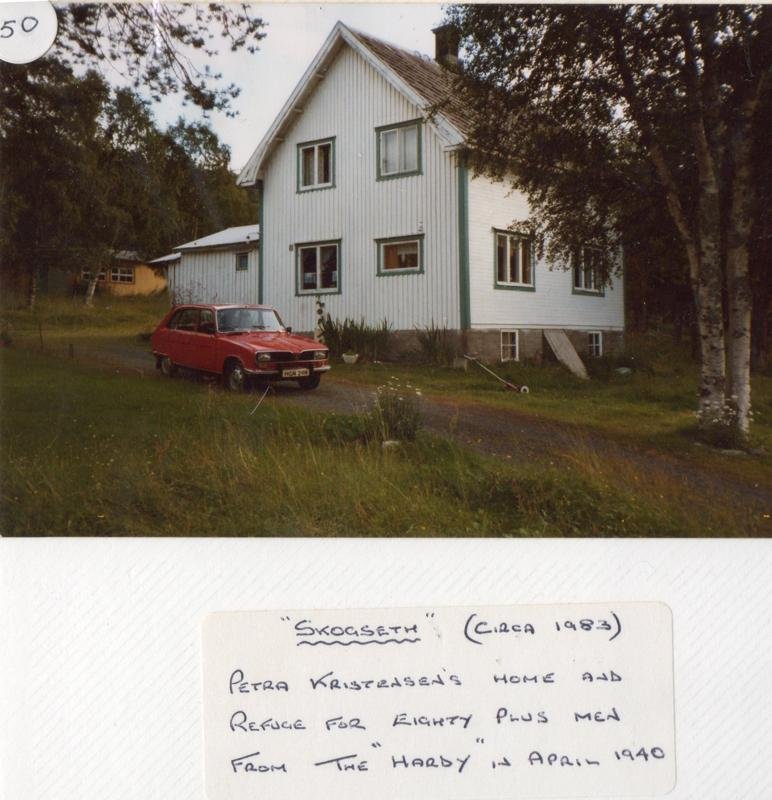

At about 1300 hours we made a move down the road away from Narvik and we were treated with many kindnesses by the Norwegians, in the way of food and clothing and other comforts. Eventually at about 7pm. We reached a village called Ballangen were they opened a big centrally heated school for us and gave us tea, rye bread and some sausages to eat. It didn’t take us long to get off to sleep that night but it took a bit more effort to get us up the next morning. All that day the people were bringing up bedding, clothes and food. They treated us well and the only way we could help them, by way of repayment, was to give a hand at clearing away snow, which we all willingly did.

During the day we visited the wounded in the hospital and they were as glad to see us as we were to see them. We could all now find time enough to spare a moment or two for those, some of whom were very close friends, who were not lucky enough to share our good fortune in surviving the battle of yesterday.

We stayed in Ballanger until the day of the second Battle of Narvik. This was on Saturday April 13th. This battle we were able to see from the attic of the school and it was a grand sight to see the ‘Tribal’ class destroyers driving’ Jerry’ step by step back up the Fiord, with ‘ Warspite’ bringing up the rear and sending salvo after salvo up the fiord which must have had a great de-moralising effect on the German destroyer crews. The Torpedo officer, Lt. Heppel, put out in a local boat to try and contact one of our ships, and on the way back picked up a deserted German motor launch. This he took over to continue his mission. In the meantime the British ships continued to move up the fiord out of our vision, but we could hear the noise of battle as gunfire echoed and re-echoed through the fiords. Lt. Heppel, made contact with the ‘Ivanhoe’ which very shortly came into Ballangan pier and took us off, and at the same time landed an armed guard to look after our wounded in the hospital.

The next morning we were transferred to different ships and I went on board the ‘Hero’ which was soon on the move down the fiord to the open sea. Orders were then received to join ‘Warspite’ in patrolling an area which we thought to be in the vicinity of the entrance to the fiord. We remained in this area with ‘Warspite’ until Thursday. Nothing by way of excitement happened during this time, but on Thursday we were told to sail for Rosyth which pleased us no end. On the next evening, Friday, we heard on the news that the survivors of the ‘Hardy’ were arriving in London ‘at any minute now’…. but obviously not our little group, here we were still out in the middle of the North Sea somewhere. Just twenty minutes after this announcement the ‘Hero’ turned about and once more made a heading for the Narvik area where we arrived on Sunday 21st April in the afternoon. I can’t express how we felt, but anyone who reads this may well imagine. Hardly had we dropped anchor than along came three German planes and dropped bombs. Fifteen minutes later, back they came to drop more, and shortly after this was followed by yet another attack. No damage was suffered in any of the raids.

That same night we, the ‘Hardy’ survivors were transferred to the troopship ‘Franconia’ who also re-embarked six hundred troops whom, it seemed she had transported to Norway earlier. We sailed again for Home at 0800 hours on Tuesday 23rd of April. We had one escort for a little way and then were left to proceed on our own. All went well until 0200 hours on Friday morning, when we were all awakened by a terrific explosion. I was out and had my lifebelt on in no time, and then there was another explosion. I just stood there in the cabin, and well, I was quite surprised that the ship didn’t heel over, or feel as though she was sinking. We made our way up towards the upper decks, but were stopped by the Master at Arms, who was saying that we had been met by an escort during the night and they were dropping depth charges. The explanation sounded feasible so we made our way back down to our bunks and sleep again. The next morning the Captain passed a message to us all saying that during the night we had been attacked by torpedo’s from a submarine and that they had exploded either in the ships wake or at the end of their run. The next morning, Saturday 27thApril, we arrived safely in Greenock and were soon on our way to Plymouth. The Barrack staff re-kitted, paid and generally processed us so that I was home on leave by 8pm on Sunday 28th of April, much to the relief of my family, who were really without word of our well being since the events of 10th April and the First Battle of Narvik.

The people of the home village of Stoke Canon (four miles from Exeter) gave me a great welcombe home and presented me with a gold watch engraved as follows. ‘Presented to Leslie J. Smale as an appreciation of services rendered on H.M.S. Hardy at Narvik April 10th. 1940 by friends at Stoke Canon’. In addition to this, they used the balance of the village collection to buy five War Savings Certificates in my name.

Ron Cope says

It was a privilege to meet Les and Barbara at their home in Crediton recently. Still young at heart and keeping up with modern technology on the internet. A more modest man I have never met. I had to persuade him to let Peter set up this dedicated section. I am in debt to Les being, other than Harry Rogers (passed away 12th October 2010) a survivor on Hardy having provided me with his written account. Importantly which he wrote shortly after the events.

Best of health to you both in the future. Ron

Ron Lucas says

I am a friend of a relation of Les Smale. My father was in the RN (HMS Grindall – Captain Class frigate) during WWII and said very little but when you read these accounts its seems so real and frightening you have to admire these sailors doing their duty in such conditions

Barry Smale says

As Les Smale’s nephew I have to say how proud I felt whilst reading my Uncles account of event’s aboard HMS Hardy. Although I knew he had been recognised and awarded for something he did in the Second World War, I was never told of the full extent of his actions or the events that took place. My Dad, (front, left side in the picture of Uncle Les’s presentation in the village hall), who is now deceased, also served in the Navy and I know he was very proud of his elder brother. Once I discovered this article I passed it on to members of my immediate family and also to friends, the family are all very proud and friends have expressed their fascination in the detail of his account.

Ron Cope says

I would just like to add a little to Les’ story. In my quest to gather further accounts from those families associated with HMS Hardy I have managed to find another survivor. He was mentioned by Les in the above account as a ‘wounded signalman’. It was infact Ralph Brigginshaw aged nineteen, who was on the flagdeck when it took a hit from one of the salvoes. It resulted in fatalities, however, Ralph, whilst unconscious for three days, and his shipmate Signalman ‘Ginger’ Turner survived both were badly wounded. They were fortunate, eventually arriving at a hospital in ‘Grandal Sykehus’ on the island of ‘Vestvagey’ Lofoten Wall. Ralph was kept there for six weeks before being cared for by a local family. However, he was suddenly told to get ready for transport in a ‘fishing boat’. To quote Ralph ” I had my 20th birthday cruising up the fjord”. By then he had lost touch with ‘Ginger’. Ralph finally arrived two days later at Tromso, just in time to catch the hospital ship ‘Atlantis’. Arriving at Liverpool on the 9th June 1940. Still needing to be carried on a stretcher, by train Ralph was sent to the ‘Inglefield’ hospital near Glasgow. In July 1940 Ralph wrote to his shipmate ‘Ginger’ Turner. Sadly the reply came from Ginger’s mother to say that a week prior to his discharge from hospital he had been drowned in a sailing accident. Ralph spent two and half years hospitalised. He served in the RN till 1950. He took a correspondence courses in radio engineering and eventually was a ‘radar engineer’ for 24 years at Gatwick Airport. Ralph still lives in Crawley with his wife Betty.

Another comforting ending out of all the trauma and grief from those fateful days in April 1940. Ron Cope

Ron Cope says

It is with sadness to hear that Les Smale BEM passed away on 11th June 2011. I send mine and my family’s sympathy to Barbara and Les’ immediate family. As I have previously described, Les was a very modest man. He served his country both at war and after in the Royal Navy, then in the Coast Guard. God Bless. From Ron Cope

Bill Sanders says

I first met Les in the early nineties when, as an ex-Shotley boy I joined the local Exeter branch of the “H.M.S. Ganges Association”. Les was already a member and I didn’t know much about him until I mentioned in casual conversation that my wife Bjorg came from a small village near Ballangen in Norway, Les instantly replied “I walked 15 b””y miles through the snow to Ballangen schoolhouse in April 1940. I then knew immediately that he was a veteran of the “Hardy” and the first Narvik sea battle. In the early seventies I had started to compile, with the help of Ron Cope’s father,Cyril, an album of eye witness accounts from veterans,Norwegians and Germans, unfortunately there were a few omissions which Les was able to explain in his quiet articulate manner, for this I was very grateful. Les Smale was one of the most interesting old “Sailors” I ever met. “God Bless Him”

Paula Brink says

Les Smale’s wife Barbara is my mother’s cousin.

Mom and I had a great visit with Barbara and Leslie in 2008 and they showed us all around beautiful Devon.

Leslie told us the story of the HMS Hardy in his quiet way with his dry sense of humour.

We are very saddened by his passing, he was a lovely, funny,interesting man.

Ron Cope says

I would just like to say to Les’ wife Barbara and his family, that I have almost completed the first draft of my book. Thankfully, I was able to meet Les, whom gave me his fascinating personal story of his experiences in the ‘1st Battle of Narvik’. I am in debt to him, as it will play a large part in my attempts to provide a comprehensive and historical account for future generations. The ‘sun has gone over the yard arm’, so I can now raise my glass to Les Smale.

RON COPE says

Message from Ron Cope. I have spent six years following up from my father’s documents / audio tapes of his experience in the First Battle of Narvik. This led to making a significant number of contacts with other families associated with the crewmen of the other ships. A lot of these came by way of this website and kindly assisted by the owner Peter Mitchell Subsequently, my book ‘Attack at Dawn’is published in April the 75th Anniversary of both the First and Second battles. The book focuses on the crewmen of ‘Hardy’ and a following book in summer will be about the ‘Hunter’ crew. If anyone would like to purchase a copy then the ISBN 978-1-909477-97-1 from Amazon or Waterstones. Or contact me for a signed copy (roncope@btinternet.com) Thanks Ron

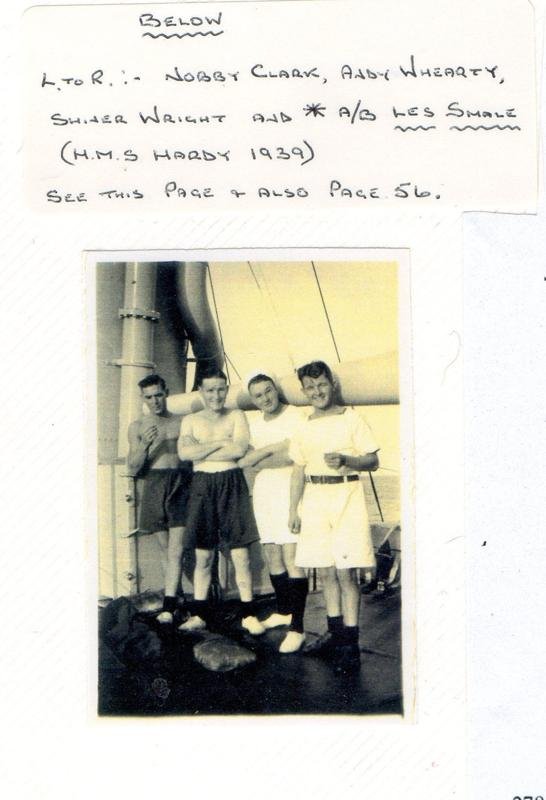

Penny Elliott nee Clark says

My dad was Nobby Clark the picture in chapter 5, I found this article very interesting as my dad would not speak of the war in front of me as it was not for my ears, but at parties my dad and uncles use to speak about the war but went silent when the ladies were about so if anyone knew of my dad Nobby Clark I would be interested to hear from you.

Ron Cope says

Penny, my first book “Attack at Dawn” mentions your Dad and there is a photograph of him at one of the Narvik Association Reunions. Book can be purchased at ‘Amazon’ books UK. or ordered from your local library. Best Wishes Ron Cope