I first saw the Vasa twenty years ago. I had heard of her many years before that, and so when I was on a business trip to Sweden I made a six hundred mile detour to see her. Then she was in a temporary museum and I wrote the following article for Sub Aqua Scene. Since then she has been moved to her permanent home, the other side of Stockholm, nearer to the centre, where she is displayed with all her artefacts and cannons. Over 750,000 people visit her each year. The inside of the museum is very dark, and you have to go through air tight doors which control the humidity. The Vasa is there in all her glory, but to my mind she has lost some of the impact that she had in the old place, when it was still a bit rough and ready and not so many concessions had been made to the tourist trade.

This feeling soon fades however as you walk around her. She is a fantastic ship, and the Swede’s have done a tremendous job of preserving her. She is supposed to be the largest relic ever recovered and preserved, but that’s not her claim to fame. Her main claim, in my view, is that she just is. By just being there she justifies all that effort and money, because she is a thing of wonder. Don’t ever think that marine archaeology is boring and meaningless. A lot of people, it seems to me, try to make it so, but the Vasa defies all that. She is a genuine time capsule, and we are all the richer for it.

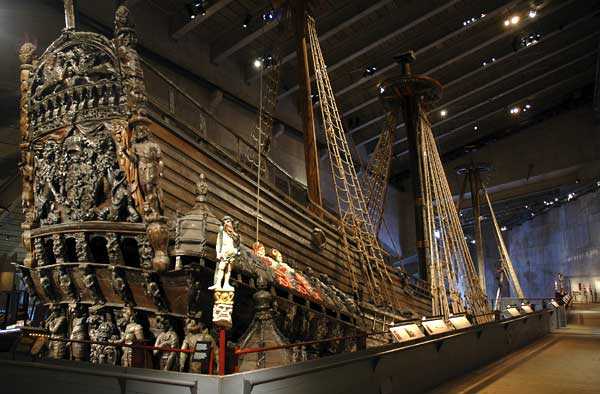

The Article: Sunday August 10 1628, a beautiful sunny day and the crowds gathering on the small islands that surround Stockholm harbour were in festive mood, for they had come to see the maiden voyage of the Navy’s latest and most powerful fighting ship, Wasa. As the magnificent new ship left the quay, the crew and their families who had been allowed on board for the big day waved and cheered excitedly. Sails were unfurled, and as the ship gathered way the brilliant sunshine reflected off the exquisite gold leaf that had been used extensively on the great carvings that adorned the Vasa’s stern-castle. As her guns fired the Swedish national Salute, she looked every inch the power and glory of Sweden’s great naval ambitions. Only ten minutes later those ambitions were mere dreams as the Vasa, caught in a great gust of wind, heeled over, and with water pouring in through her open gun-ports turned right over and with all sails set, her flag still flying, sank swiftly to the bottom. After only fifteen hundred yards the Vasa’s maiden voyage was over. Thankfully most of the crew and their families were rescued by the multitude of small boats gathered to watch the spectacle.

In the aftermath of the disaster the contractors and builders immediately started blaming each other, secure in the knowledge that the evidence was now safe in over one hundred and fifteen feet of dark cold water. Still the Navy Board after conducting enquiries soon realised that bad design was the main fault. The Vasa had too little beam for her length, too much top hamper, and most damaging of all, not enough ballast. Within three days of the Vasa sinking, an Englishman called Ian Buller had arrived to try and salvage her. With the Vasa lying on her side in the mud, conditions to say the least were very difficult and in the end Buller had to give it up. However he did manage to get the Vasa into an upright position. How on earth he managed this nobody is quite sure, but by doing so he undoubtedly contributed to the successful lifting of the Wasa over three hundred years later.

Nothing else much happened to the Vasa until 1653 when two Swede’s, Hans Albrecht von Treileben and Andreas Peckell managed to recover over fifty of the Vasa’s bronze cannon using a primitive diving bell. They also had a form of wetsuit made of leather to keep them warm, and seeing that each cannon weighed over one and a half tons and took hours of painstaking work to locate, they would really have needed them to help bring off this remarkable feat of salvage. After that however people lost interest, and the Vasa became a forgotten ship, forgotten that is until 1956 when Anders Franzen, a man dedicated to finding the warship, finally succeeded after a long and systematic search, with of all things a specially made core sampler. He didn’t dive, and anyway the mud was far to thick to see anything, so he thought that if he dropped his special core sampler in the area where he thought the Vasa was, he should come up with a bit of timber. It sounds ridiculous doesn’t it? But in August 1956 it delivered the goods, and overnight Frazen became internationally famous.

Not content with finding the ship, he was now determined to get it up as well, and soon he had persuaded all sorts of people from King Olaf of Sweden, to Neptune, a huge salvage firm, that his ideas were a real possibility. Once again he was proved right, but even he was flabbergasted by the results. You see the Vasa was to all intents and purposes intact, completely in one piece. All that was missing were her masts, which had broken off when she had turned over and sunk. When the Vasa finally hit the surface after three hundred and thirty years on the bottom it was the most magnificent sight that any ‘shipwrecker’ could possibly hope to see, and Frazen was triumphant.

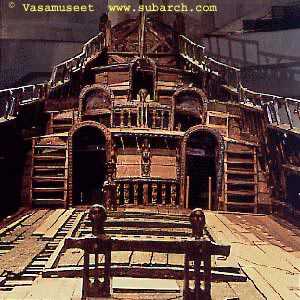

Today the Vasa stands on a floating pontoon covered with an aluminium shell, and is part of Sweden’s National Maritime Museum. Although the raising of the Wasa had been an incredibly long and arduous task, the marine archaeologists soon realised that her preservation was going to be even harder. There were no experts, and no information on how to do it, as nobody had ever tried anything like it before. Still they had to do something. There was over thirty two thousand cubic feet of timber, most of it oak, and if they allowed it to dry out it would shrink to less than half its size, cracking the hull to pieces. There were also the more ‘minor’ problems concerning the restoration of over a thousand wooden carvings that had adorned the ship, and some twelve thousand individual items showing what life had been like aboard the ship. The problem was solved by using a substance called Polyglycol (P.E.G.).

This penetrated into the timbers and stabilized its dimensions. Even so, in the first year (1962) over ninety tons of P.E.G. was sprayed onto the Vasa, and difficulties were discovered in the drying process. In the end the ship was sprayed day and night for the next ten years, until finally it could absorb no more of the P.E.G. solution. In 1972, a two-year after phase treatment commenced, but by then the scientists had realised that it would probably take another twenty years for the timbers to finally dry and properly condition.

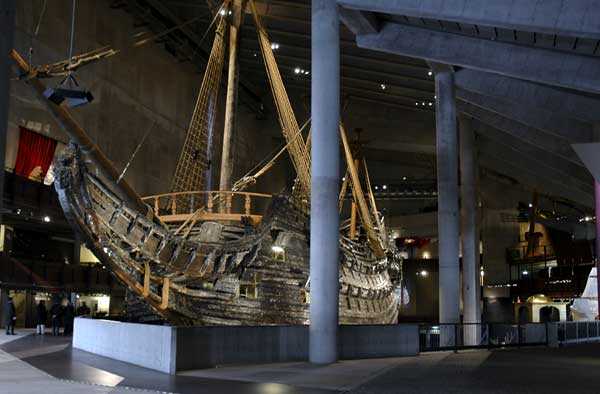

Now to me most Museums are dull unimaginative places, and it was more in hope than expectation that I went to see the Vasa on a recent trip to Sweden. The Museum outside is a drab windswept place looking somewhat like a disused aircraft hangar, but when you walk inside you don’t notice the bare surroundings because the Vasa takes your breath away. It almost fills its temporary home, and all around it is wooden and steel scaffolding that allows you to see the ship from every angle, both above and below. As you wander about looking and touching this three hundred year old relic of a bygone age, you can see why it has been on show. The Vasa has not been tarted up for the tourists; in fact she looks rather as if she is in a dry dock awaiting some minor repairs. All the original carvings have been put back, but the Museum decided to leave them and the ship in its natural colour, a sort of grey brown.

In order to show the vivid colours, they made copies of the carvings, especially the enormous stern-castle set pieces, and then painted them in their original colours. They have not done all of them yet, but the ones that are finished hang on the walls and are absolutely stunning. But it is the Vasa that is undeniably the star. She is so much bigger than you expect, and so well preserved that she looks almost ready to sail away. The smells and colouring that the P.E.G. have left in the wood, combined with the dim lighting (its all controlled for humidity) give the ship an almost magical ghostly quality, the sort of feeling that you sometimes get in great cathedrals. In a way I suppose that’s what this building has become, a cathedral that houses not only the last remains of a once great Naval power, but it also seems to symbolise to the Swedish their fervent national pride. Look at me the Vasa seems to say, for I was the Power and the Glory.

Stephanie Dryer says

Beautifully written.