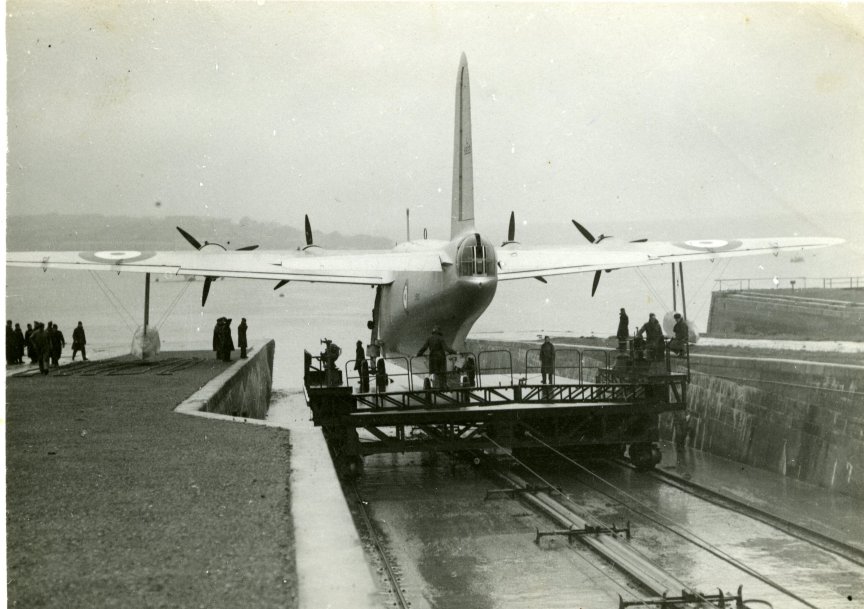

During the Second World War, Mountbatten was home to No. 10 Squadron Royal Australian Air force, and those now deserted hangars hummed with activity as they serviced , the needs of the Squadron’s aircraft, Sunderland flying boats. Named after Admiral Batten a Civil War Governor of the ‘headland and tower’, the history of Mountbatten goes back to the Great War when in 1917 R.N.A.S. Cattewater Seaplane Station was opened as part of a comprehensive chain of South West bases, who’s main task was to bomb U. boats in the Western Approaches. After the Great War ended most of the South Western chain of bases were disbanded, but R.N .A.S Cattewater stayed in operation if only as a storage and cadre unit. However as the decade wore on a modest expansion in the role of the seaplane saw Mountbatten return to full operation, and on October 1 1928 Cattewater Station was renamed Mountbatten and that is the way things have stayed up till the present day.

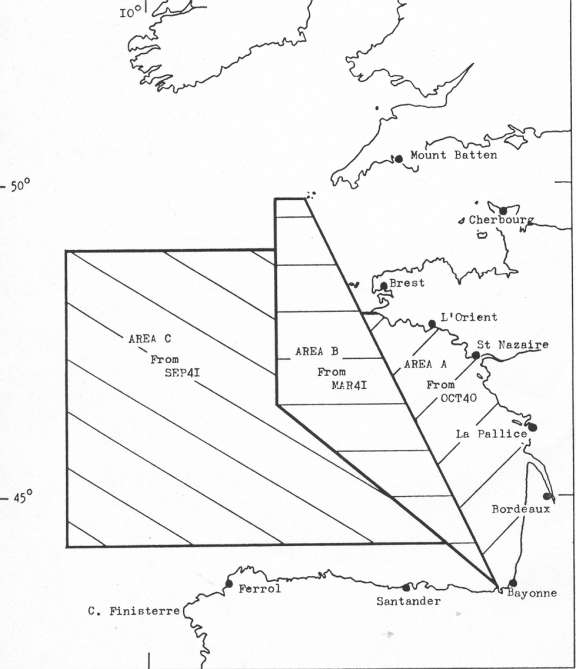

During the early thirties life at Mountbatten was pleasant and peaceful. Training flights and the odd cruise to the Continent or the Mediterranean relieved the boredom. However as the war in Europe became increasingly apparent 204 Squadron were re-equipped with Mountbatten’s first Sunderlands in June 1939, and soon became responsible for patrolling the Western Approaches where if hostilities broke out they would once more hunt down the U. boats in one of their favourite killing grounds. When War was finally declared, 204 Squadron had six Sunderlands fully operational, and on 4 September they launched their first operational anti-submarine patrol into a grey Plymouth dawn. After nine hours of uneventful patrolling the crew brought the Sunderland safely back only to be shot at by the local anti-aircraft battery, who were thankfully long on determination, but short on eyesight.

On 1 April 1940, 204 Squadron moved to Sullom Voe in the Shetlandsand the Australians moved in, in the shape of 10 Squadron Royal Australian Airforce. They were to stay for the rest of the war hunting submarines with a brief departure to Wales during the height of the Plymouth Blitz. This made life impossible for the Sunderland crews, who with Plymouth Sound so jammed with shipping could hardly take off without hitting either wandering merchant ships or Naval craft rushing around the Sound trying to avoid being straffed by enemy planes. As the war ended many of the Squadron’s Australian personnel were repatriated, and on 5 November 1945 10 Squadron left for good and Mountbatten was transferred from Coastal Command to Maintenance Command. It was the end of its days as a flying boat station.

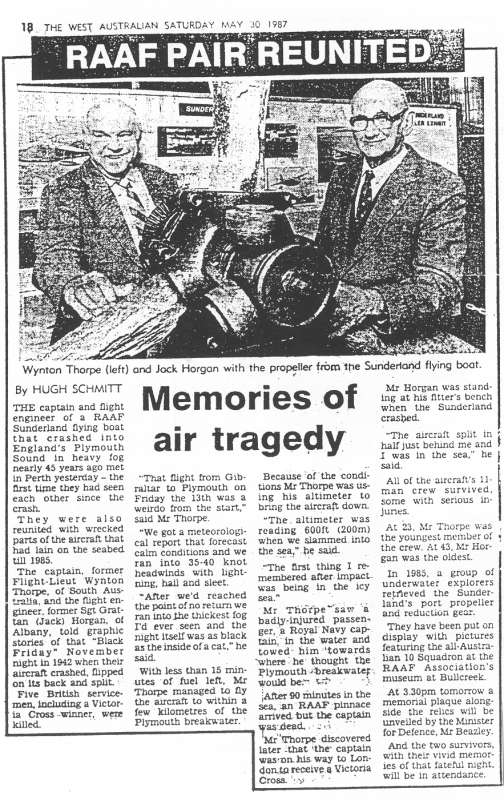

Besides hunting U. boats and patrolling the Western Approaches the Sunder lands were also used for transporting personnel to bases as far away as Gibraltar. It was on such a mission that disaster struck for the flying boat captained by Flight Lieutenant Wynton Thorpe. The flight from Gibraltar to Plymouth during November 1942 got off to a bad start right from the beginning. For one thing it was Friday 13, and for another the meteorologists managed to get the weather completely wrong. As Wynton Thorpe, his eleven man crew and five passengers left Gibraltar the forecast was for calm conditions. Almost at once they ran into forty knot headwinds, with lightning and hail thrown in for good measure.

As the flying boat bucked and swooped its way towards England the weather increased in ferocity, but by then the boat was at the point of no return. All Wynton Thorpe and his crew could do now was tough it out. At last the weather changed. No more hail and sleet, just thick, black fog. Thorpe later said that “it was the thickest fog he had ever seen” and “that the night was as black as the inside of a cat”. With great skill Wynton Thorpe managed to fly the aircraft to within a few miles of the Plymouth Breakwater, but the fog was so bad he was unsure of where he was or how high he might be above the sea.

With less than fifteen minutes of fuel left he decided to try for a landing. Because the conditions were so bad, he had to rely completely on his altimeter to bring the seaplane down. He was completely blind. When the altimeter was still reading 600 feet the Sunderland slammed into the water. The shock of the impact devastated the aircraft and split it right in half throwing Thorpe straight into the sea. Almost at once he saw one of the passengers, a Naval Captain, lying in the water and started to tow him to where he thought the Breakwater was. They remained in the sea for over ninety minutes before a rescue pinnance finally found them. Alas the bravery and determination of Wynton Thorpe was to no avail. The Naval Captain was dead and Thorpe near collapse. In the end all eleven crew were saved although most sustained serious injuries. None of the five passengers survived. Later, after he had recovered, Wynton Thorpe was to wonder at the irony of his lucky escape. The Naval Captain, that he had tried so hard to rescue, had only been on board so that he could come to London to receive the highest award of all, the Victoria Cross. What a terrible price to pay for the Nation’s gratitude.

Today all this would just be a fading memory but for a diver called Neil Griffin. He and his mates used to dive around the Breakwater quite a bit and one day they were diving on the inside area between the Breakwater Fort and the Lighthouse when Neil found a large piece of aluminium framing. Now the bottom here is very silty mud, and by the time he had completed his investigation of the metal frame he had stirred up the silt so much that he could not see a thing and so decided to call it a day and surfaced. Unfortunately the boat was drifting, and by the time he got picked up and was back on board he really had very little idea of where he had actually been diving.

Still Neil is nothing if not determined, and over the next few months he searched and searched (talk about positive thinking) and finally found the remains of what he thought were two Sunderlands. One was really mangled and spread over quite a large area, but the other was recognisable as two bits of one plane. Over several dives Neil explored this aircraft and after finding the port propellor and reduction gear, decided to raise these along with some other artefacts and offer them to the Australian Airforce Museum.

Unfortunately Neil’s position finding was not as accurate as he thought it was, and it took him some time to relocate the sunken Sunderland. By this time the weather had deteriorated and silt had moved over various parts of the wreckage making orientation underwater somewhat difficult. After a lot of false starts Neil finally relocated the Sunderland’s propellor and the reduction gear, and in a blaze of organization raised the lot and carted it off to R.A.F. Mountbatten for safe keeping

Now if you or I had done this a local museum would probably have told us to go away and take our rubbish with us, but not the Australians. They were very keen to have the propellor and reduction gear for display at the R.A.A.F.’s Association’s Museum at Bull Creek near Perth. After the ground engineers at Mountbatten had tidied up the prop and crated it up, off it was shipped to Australia, and that is where the best bit of this story comes in. Still living in Australia were Wynton Thorpe and his flight engineer on that fateful day Jack Horgan. When the R.A.A.F. Association told them of Neil’s find they were dumfounded. They had not seen each other for over forty years and so the Association invited them down to Perth to be reunited with each other, and the remains of their once proud Sunderland flying boat. You can imagine their emotion and their vivid memories of that dreadful day, and of all their lost comrades in 10 Squadron.

On May 31 1987 they stood alongside the Australian Minister for Defence and unveiled a memorial plaque at the Bull Creek Museum alongside the Blades of their old Sunderland. For the two veteran survivors it was a vindication of their’s and their comrades committment and sacrifice all those years ago. For Neil, unfortunately only in there spirit, it was a wonderful moment. All the effort he had put in was amply rewarded by the gratitude of the old flyers and the Royal Australian Airforce. He had discovered the wreck and returned it back to its rightful owners. Not many of us will ever get a chance to do that, especially with something that has already passed into the history books.

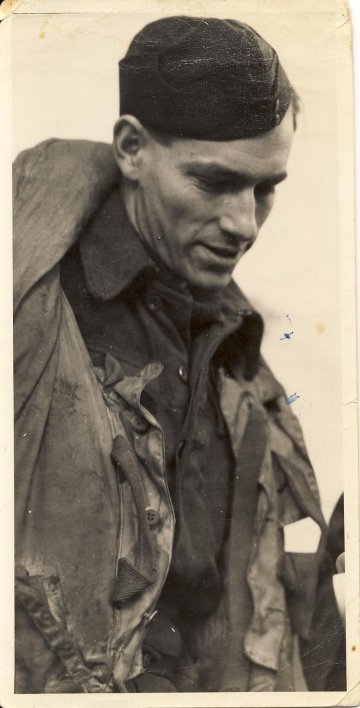

Squadron Leader Flight Sergeant Gordon Craig

I am very grateful to Helen Craig for the following photos of her father Squadron Leader Flight Sergeant Gordon Craig. He flew with 10 Squadron on the Sunderland flying boats out of Plymouth, hunting for submarines.

He told her many stories of landing in the cold waters of Plymouth Sound, limping into port with all the crew up on one of the wings to keep the plane upright and floating until it reached its slip. Sadly he passed away in 2006 aged 83.

My father was killed in WW2. He was a Flight Engineer (aka ‘cannon fodder’ – a rear gunner) in the 10th.

Three weeks after I was born, in February 1942, he was sent to join his squadron in Mount Batten. His plane was shot down over the Bay of Biscay in September of the following year and he never had leave back to Australia. He was 23 years old and my mother was a widow at 20. I know that Sunderlands, because they could fly low, below the radar, frequently were able to pick up survivors from other planes and his plane had been mentioned in dispatches only the previous week for doing this. Unusually, no survivors or even any wreckage of DV969, were ever found. I have been to the War Memorial in Canberra and read in the log book the handwritten exchange between my father’s plane, at that time flying over the Bay of Biscay, and the base, where the pilot reports a number of Junker 88s coming towards them. There was no further entry.

Valerie Wells says

I was born February 1943. I can recall being in a boat, probably going to Cawsand,at what must have been a very early age, but I do remember seeing a Flying Boat in Plymouth Sound and being told it was a Sunderland. As we neared the plane I remember it seemed enormous. Can anyone tell me what year this must have been? I wouldn’t be surprised if someone said 1945. I am often told I have a good memory of my very early years (remembering even being In a pushchair with the rainfall up connected to the pram hood!

Sandra McDonald says

I believe a cousin of mine Colin Stewart Cameron was aboard, he was a gunner 10th Squadron 422410, K.I.A. 21st September 1943. I would love to have this verified. I am researching his story at present.

Cheers.

Gram Cameron says

+Sandra McDonald ,

re:- “I believe a cousin of mine Colin Stewart Cameron was aboard, he was a gunner 10th Squadron 422410, K.I.A. 21st September 1943. I would love to have this verified. I am researching his story at present. ”

Yes, Sandra , my uncle Colin Stewart Cameron was on fated DV969 …

Colin is shown in the above photo – back row – on the Far Right opposite flt eng Leech

Richard Stead says

A PILOT’S STORY – GEORGE STEAD DFC

I recently completed the private publication of my father George Stead’s memoirs which covers his forty years flying from 1928 in New Zealand to retiring in 1963 from BOAC. His account includes chapters of his time flying Sunderlands with Coastal Command in the North Atlantic, Mediterranean and Gambia, and in 1941 his appointment as Chief Flying Instructor at No. 4 OTU in Invergordon. He also recounts his time after the war flying Sunderlands with BOAC out of Poole Harbour to the Far East.

My father wrote his memoirs after he retired but sadly did not manage to have them published in his lifetime and this publication is very much a personal mission for him. Please visit my website http://www.cdarts.co.uk for further details and a chance to purchase a copy.

John Holter says

I am an 87year old Plymouthian, and lived in Plymouth from 1933 until 1970. I now live in Bedford. I remember seeing the Sunderlands taxiing from The Sound and moored at Mount Batten. I actually saw one take off from Mount Batten and fly overThe Citidel, wondering if it was going to make it, but it did. I was also stationed at Mount Batten, in the Met Office, during the 1960s.

If anyone remembers me, or wishes to make contact, I am more than happy to respond.

I lived in John Street during the war and attended North Road Primary and Cobourg Street (Public Secondary)Schools.

John Holter

Phil says

My school cadet force spent a week at Mount Batten in May 1955 (at time of the general election). A Sunderland was flown in from Pembroke Dock to give us a air experience, and what a thrill it was for a 15 to. We also had a voyagé on a high speed launch as Mount Batten was an air sea rescue base then. This could have been the last Sunderland flight from Plymouth Sound as the type was withdrawn 4 years later.

Jeff Atkins says

Are folks aware that Corgi has made a fitting Collector’s Limited Edition tribute to the crews of the Short Sunderland, and and to No. 10 RAF Sqn in its production of Sunderland W3999/RB-Y.

21st June 1942, when Sunderland W3999 (crew of 11) took off from RAF Mount Batten to try and locate a dinghy containing the crew of a ditched Coastal Command No.172 Squadron Vickers Wellington.

On reaching the search area, the Sunderland, along with an accompanying Whitley patrol aircraft, were attacked by a German Arado Ar196 ?oat plane, with the Sunderland taking a number of hits. Losing height immediately, the ?ying boat effected a landing on the open sea, but at the end of its landing run was seen to explode and sink beneath the waves. Coming under further attack, the Whitley took evasive action, before setting course for home, with the crew having the unpleasant task of con?rming that there were no survivors from this tragic incident. (Ref., and with thanks to: Warkswings Diecast Models).

We shall remember them.

Mick Lobb says

My uncle, by marriage to my aunt, a Plymouth lass, was a crew member of W3999 and I am a proud owner of the Corgi model. They had been married for just 6 weeks when he was killed. She later married an American, a wonderful man who, at the the age of 93 honoured her lifelong wish to be with Snowy taking her ashes back to Plymouth then sailing on a ferry across the Bay of Biscay to scatter them where Snowy sadly met his end. Bless them all.

David coles says

Sunderland were here some time after the war I remember them well used to go come over our house low heading for the sound to land saw them taking off and landing in the sound .

Richard Hodgkinson says

My father, Vic Hodgkinson, was in 10 Squadron RAAF, flying Sunderland flying boats from Mount Batten, Pembroke Dock and Oban, before returning to Australia in 1942 to fly a variety of flying boats including Catalinas, Martin Mariners and ex-Dutch Dornier 24s. He returned to the UK in 1946 and flew for BOAC before retiring in 1971. He’s the silent officer in the newsreel at the end of this link http://www.atlantikwall.co.uk/atlantikwall/edev_mont_batten.php

Pen & Sword will be publishing his RAAF career next year as “My Flying Boat War”.

Somewhere in his papers I have a hand-drawn map that he made of Sunderland wrecks in Plymouth Sound…