The Torrey Canyon, Amoco Cadiz, and the Exxon Valdez are all infamous for one thing, oil pollution. In the mid 1800’s that phrase had no meaning at all, and if you had told people that a hundred years later oil pollution would be on of the world’s worst problems, they would probably have said, so what. You cannot really blame them; after all they had enough problems of their own. Nowadays we all complain about cars polluting the atmosphere, but imagine London in the horsedrawn 1850’s. With a population of well over two and a half million, there were up to a million horses working in Englands capital city, depositing something like sixteen thousand tons of horse dung on the streets every day. Just imagine it. Give me good old carbon dioxide any day. Still as the internal combustion engine started to replace the horse, petrol became more and more in demand and soon ships were being specifically designed to transport it. The controversial age of the oil tanker had dawned.

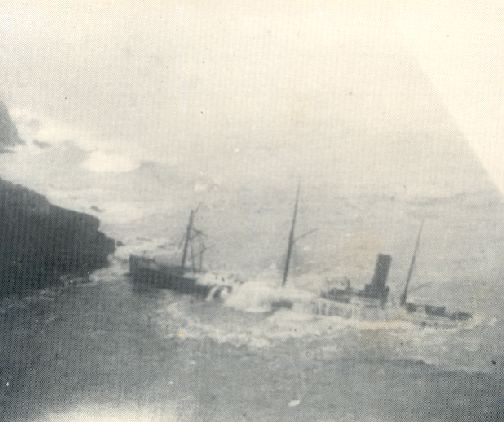

One of the first ships to be specially designed for oil shipments was the Russian steamer Blesk, and she was to have the unhappy distinction of being the very first oil tanker to be wrecked on the coast of the British Isles. 298 feet long, and loaded with 3180 tons of petro-oil; the Blesk was built to have all her holds at the front and her engines at the stern. Defying convention of the times her bridge and accommodation was set well back towards the stern instead of being placed amidships. This first design was almost right first time and did not really alter until the first of the supertankers came along in the early Sixties. On November 14 1896 the Blesk left Odessa bound for Hamburg. On 1st December the Blesk was at the entrance to the English Channel and Captain Adolph Deme, confident in his navigation, cracked on at the Blesk’s full speed which was around ten knots. It was a thick, dark day with heavy rain, and when Captain Deme saw a light blinking ahead in the murk he consulted his chart and decided that he was about to pass the Corbiere light just off Jersey.

As he altered his course to come slightly more to the north it never occurred to him that the light was actually coming from the Eddystone Lighthouse. By altering course Captain Deme had now aimed the Blesk straight at the coast of Devon. As the rain continued its downpour the afternoon drew into the darkness of night, and the visibility dropped to nil. But still Captain Deme, happily pacing his bridge had no idea of the impending disaster that was shortly to happen. At just after nine o’clock that evening the Blesk, still forging ahead at ten knots, ran full tilt into the Greystone rock and ran hard up onto the Greystone Ledges just to the east of Bolt Tail. Because she had hit so hard and ridden up over the Ledges, it was fairly obvious even at that early stage that the Blesk would never get off.

Captain Deme ordered flares and distress rockets to be launched, and opening the ships firearms locker issued handguns to his officers and told them to fire those as well. With the seas pounding her stern, and the noise of her hull grating and banging on the rocks, it must have been a terrifying time for all the crew. However they all kept their heads and nobody tried to commit certain suicide by attempting to jump ship. At last the Hope Cove Lifeboat appeared, and in the space of two trips managed to save all forty three crew and take them to the safety of Hope Cove. By the next day it was a rarity to see oil floating on the water and people came from miles around to stand on the clifftops and watch the oil stain the sea black all along this part of the coast. After a while however the novelty wore off as the fumes made people vomit, and the stench grew horrendous. Local reports at the time said that you could smell the oil in Totnes, over twenty miles away. As the oil spread it poisoned all the fish between Bigbury and Prawle Point, and soon every tide brought ashore oiled up lobster, crabs, bream and mullet, all killed by the Blesk’s escaping cargo. It was a sad time for Hope Cove and Salcombe and a glimpse of the ecological catastrophes yet to come.

Today if you swim around the Greystone Ledges the one thing you will not find is any wreckage belonging to the Blesk. However if you swim along Redrot Ledges, which are more towards Bolt Tail, you will come across plenty of boiler coke, solidified lumps of tar, and a certain amount of wreckage. It is my belief that here in about thirty five feet of water lie the remains of the Blesk. Well I was wrong. There is wreckage here, and it might, or might not be from the Blesk. But the main wreckage is undeniably in the bay beyond. I now know this, not because I found it, but because Matt Walker, a local man took this amazing photograph from the top of the cliffs above Huge’s Hole this year.(2014) It clearly shows the outline of a ship, bows to the shore, with two boilers just a little way out too sea. I am extremely grateful to Matt Walker for the two photo’s below clearly showing the shipwreck. The two boilers are the black blobs to the upper right.

I couldn’t believe my luck. The savage winter storms had move most of the sand to reveal what was left of the ships ribs. Surely it was too good to be true? As soon as I could, I shot around to Bolt Tail and the Greystone Rock, with Dave my diving partner to take a good look. It was a flat calm sunny day, and using Matt’s photo, we soon located the wreck in about 25ft of water and dropped our anchor right by one of the boilers. Even though the sea was calm, there was quite a ground surge, which made things a bit tricky as all the metal sticking out of the sand was razor sharp. However there was so much to see that we soon got used to it, and spent a happy hour exploring all the bits of metal and plate, trying to piece the wreck together. The two boilers were fairly intact, except for one, which had its top missing. The ribs outlined in the photo, were in fact bits of metal sticking out of the sand, covered with a coating of weed.

On the bottom, these did not really show up as lines, so it was difficult to establish quite where you were on the wreck. However, we soon made our way to the bow area, which was right by the rocks, and it was here that we found a mass of plating, anchor chain, but alas no anchors. Bollards and the remains of a winch were half buried in the sand as well as some lumps of tar. We did not find the engine block, so it would seem that the people that bought the ship at auction salvaged it where it lay, cutting up the plate down towards the bottom of the hull, much as was done to the |Demetrios at Prawle Point. There is quite a lot of brass lying just hidden under the sand, and no doubt that much of the wreckage is still covered in sand, so who knows what is left unseen. It made for a fascinating dive, and in the next month or so, we managed to visit the wreck a for a couple of dives, but the sand seemed to be moving back in, with the ground swell getting stronger. There is always next year, so lets hope the sand uncovers some more.

Once again I am indebted to Matt Walker for the pics below taken April 2015. It clearly shows that most of the sand has moved back to cover the ribs. He filmed at one of the low tides, and you can see one of the boilers sticking out of the water. Also to the left of the bay are the boilers of the Jane Rowe or Charter with a mass of iron plating and ribs, belonging to one or the other. All part of the jigsaw.

Boiler from the Blesk – – Boilers and mass of plate and ribs from the Jane Rowe or Charter.

He scrambled down the cliff – – Boiler from Jane Rowe

Ken Prowse says

What a wonderful and interesting write up.

I wonder if we might share your Link on our Website.

Many thanks

Ken Prowse (Chairman)

Matt Walker says

Dear Peter, I believe I have identified the last resting place of the Blesk. One of the positives that has come from the turmoil of last winter is that the sea was like a washing machine and removed meters of sand. At low tide when the sea is calm and clear you can look down into Hugh’s Hole from the end of Bolberry Down and quite clearly see the outline of a shipwreck. It is in identical orientation to that shown in the picture of the Blesk in your article. I live on Bolberry Down so would be happy to show you. Kind regards, Matt Walker

Matt Walker says

PS: I can send you a picture if you wish.

steve horner says

I endorse the information given to you by Matt Walker. The wreckage of the boiler lies in the centre of the cove seaward of the adit to Eastmans mine.It is visible at low water springs. The photo reflects this and if the Blesk was headed westwards down the channel she may well have struck Greystone reefs but then her bows must have swung round through 180degrees to finish up in the position shown in the photo.I would very much appreciate a copy of this photo

STeve Horner