In the 18th century, shipwreck was very much a way of life for many villages along the south Devon coast. The sheer poverty of the inhabitants is hard to imagine nowadays, but for many, even the provision of their next meal was filled with uncertainty. It is no wonder then, that when news of a shipwreck was heard, hundreds would flock to the clifftops in all weathers so as not to miss an event which could keep their bodies clothed and fed for nearly a full year. For the seafarer however, shipwreck meant only one thing, death and a pretty nasty one at that.

Still life was pretty cheap in those days, but late in the evening of 14th February 1760 a shipwreck occurred near Bolt Tail whose loss of life was so great, that even today its awful memory still lingers on.

The ship was the Ramillies, a 90-gun ship of the line, whose main claim to fame was that she had been in almost continuous service for ninety-six years. Originally built at Woolwich in 1664 as the 82 gun Katherine, she was rebuilt twice, renamed the Royal Katherine, and finally as the Ramillies in 1749, was given another 18 guns which brought her all up weight close to 1700 tons.

In 1760 the British were busy blockading the French sea ports and on the 6th February the Ramillies in company with several other ships sailed from Plymouth to join Admiral Boscowan’s Channel fleet. By the 14th, a violent southwesterly gale had sprung up, scattering the fleet and causing the Ramillies to heave-to in order to make repairs to her badly leaking hull.

The gale pushed her steadily eastwards until Bolt Tail came into sight. The sailing master, thinking that he was back off to Plymouth, mistook Bolt Tail for Rame Head and advised the Captain to run for the shelter of Plymouth Sound. As the Ramillies stood into what was really Bigbury Bay, the terrible truth dawned on the sailing master and he frantically called for full canvas as he attempted to turn the ship around.

He never really had a chance. Under the huge press of canvas the main mast crashed to the deck, closely followed by the mizzenmast. Most of the sails were now in shreds, so after dropping the anchor in order to prevent the ship becoming completely embayed, the rest of the wreckage was chopped up and thrown over the side.

Without any masts the Ramillies rode easier and with another anchor down the situation seemed almost under control. In all the panic however, it was not noticed that the anchor cables had got tangled and were continually chaffing. Soon one of them broke, and the other was not strong enough to hold the vessel in the huge seas. The sheet anchor was dropped as a last resort, but the Ramillies was doomed. She ripped past Bolt Tail and smashed her stern right into a large cave at the bottom of the cliffs.

People started dying almost immediately. Some were smashed to a pulp on the rocks; others just tossed into the heaving seas where they speedily drowned.

Almost at once the Ramillies started to break up. The last person to leave the stricken vessel was William Wise who later described the wreck as "drove into such small pieces that it appears like piles of firewood". That terrible night over 700 died, crushed or drowned at the foot of those unclimable cliffs.

The next morning the coast around Hope Cove was full of wreckage and the floating corpses kept coming ashore on each successive tide. The looting was fearful and to this day many of the old houses still have something of the Ramillies built into them.

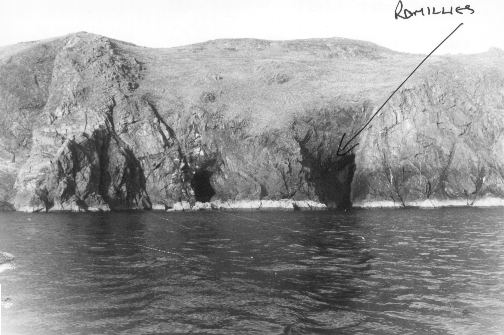

Ramillies Cove is marked on most maps, but that is not where the wreck lies. The remains of the Ramillies lie instead in the next cave to the east.

The cave is at least eighty feet high and goes in quite a long way. The seabed is made up of rock and sand, and right at its entrance, in about twenty feet of water lie three iron cannons. They are very corroded but quite unmistakable.

The undersea floor of the cave steps up about five feet here, and at the base of this rise, almost hidden in the sand lies part of the Ramillies massive wooden rudder. The only other things in the cave are some pieces of lead sheet, which presumable were used to line the ships scuppers; but just outside are all sorts of bits and pieces. There is plenty of iron crudded into the rocks and several larger pieces show quite clearly the hollows where cannon balls were stowed. Pieces of broken bottle, copper nails, and of course cannon balls are still to be found amongst the rocks, and further out still, in only thirty feet of water lies some of the hull.

I was really surprised at this. After over 200 years, I would have thought that it would have been smashed up completely, but not so. There is only about a ten foot piece that sticks up out of the sand, but it is nearly four feet high, and still more pieces of wooden keel are to be found half buried amid the sand and rocks. What’s more, some of it is lined with lead sheeting.

Seeing that really made this wreck come alive. To think that after over 200 years you can still touch part of the hull of a ship that started life way back in 1664.

After the dive the thing that you notice most of all, apart from the scenery, are the masses of seagulls wheeling in squadrons around the clifftops. Why so many? Well they do say that the seagulls are really the souls of the dead, and where else would they go?

mosaiclawns says

and they still sing about this shipwreck today

Brass Monkey – The Loss of HMS Ramillies – Live Sidmouth Folk Week 2010

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WiMZ8YwDNcY

micky says

I was lucky enough to meet Mr and Mrs MICHAEL when visiting Hope Cove. After a lousy diving season through bad weather Hope Cove offered some shelter from a northerly blast, so joined them diving on the RAMILLIES. A simple dive but well worth a bimble amongst kelp rocks down to the sandy seabed at 40ft. Viz was cracking at 30ft plus finding 3 cannon, a rudder post and wooden boards with lead sheathing. A great end to my season. Can’t wait to go again. MANY THANKS TO THE MICHAEL’S GREAT COUPLE. mickyp.

David B says

I dived the site in 1976 and can still remember the feeling of being in the area of a ship that sank over 300 years earlier with so much of it still visible. a great dive with excellent visibility still recalled every time I re-read my log books.

Mr warne says

I’ve dived on the wreck , and have the ring used on the wax that sealed letters

Steve Jones says

My grandad was among the crew of the Ramalies ship . Just found this out on ancestry .