In the early morning of the 27 June 1887 the Hamstone was shrouded in dense fog. Creeping up channel towards Dunkirk was the 844 ton French steamer Soudan, loaded with peanuts, ox hides, and oil from Senegal. The eight passengers and twenty four crew, now only hours from a safe landfall gazed worriedly out at the eerie, swirling fog and prayed that the Captain knew where he was. Unfortunately their prayers went unanswered because shortly before midday the Soudan ran straight out of the fog onto the Hamstone where she became firmly stuck. Still, with a flat calm sea the only casualty was the Captains pride. When the fog lifted that afternoon the eight passengers were rescued by a passing yacht, which took them to Salcombe where they reported the Soudan firmly stuck on the outer ledges of the Hamstone, with about twelve feet of water in her forward holds.

By that evening the tugs Vixen and Raleigh had arrived on the scene, and as the tide rose the Soudan floated free of the Hamstone enabling the two tugs to take her in tow. Although the crew had sealed off the forward holds the water was still leaking into the vessel in considerable quantities, and the Soudan became very sluggish and difficult to manoeuvre. Progress was desperately slow. By midnight the tugs had managed to tow the Soudan abreast the Mewstones and started to make the turn for the entrance to Salcombe Harbour.

With water still pouring into the forward holds passed the sealed bulkheads, the stress on the other bulkheads increased. In the end the engine room bulkhead gave way with a loud tearing noise and the tug skippers suddenly realised that they were now towing a dead weight that had the power to take them both to the bottom. Hurriedly they rushed to cut the towing hawsers now humming ominously with the strain. The Soudan seemed to catapult forward then dived bows under the waves to come to rest upright on the bottom with her mast still visible above the surface.

By the time morning came the Soudan’s cargo had started to float out of her, but the Insurers were optimistic, especially as she seemed to still be more or less in one piece. Two Belgium salvage ships, the Berger Wilhelm and the Newa, were hired to raise the wreck, and for two months they stayed on site trying every trick in the book. Air was blown into her ballast tanks, and when that failed huge air bags were placed into her holds and compressors pumped air down to them for days. Nothing happened. Next, massive chains were passed underneath her hull and secured to lifting lighters, which besides using powerful winches also used the lifting effects of the tides. But all was to no avail; the Soudan seemed determined to stay on the bottom. After a few more abortive attempts the owners and insurers gave up in despair and declared the Soudan a complete and total loss.

Today the Soudan lies in exactly the same place in about 60 feet of water on a sandy bottom. Although broken up, her stern is still reasonably intact, as are her boilers. An interesting feature of this wreck is her iron propeller with its well polished boss, a tribute to the many divers that visit her. The bows stand out of the sand with the foredeck and some bulkheads lying flat on the seabed with what appears to be part of the mainmast and boom lying across all of that. The boom leads you out onto the sand where other pieces of bulkhead and ribs lie scattered. It is an easy and compact wreck to swim around and the boilers serve as a nice central point from which to get your bearings.

Even though this wreck is very popular with visiting divers there are still small brass valves and tally’s to be found and occasionally the odd china doorknob turns up. Because of her position the Soudan is only divable for twenty minutes of slack water at both high and low tide. Even this is a bit variable and when the tide starts running it really shifts, so strict timekeeping and good boat cover are essential. The tide run also makes the visibility somewhat unpredictable. Usually it is about fifteen feet, but sometimes the tide just deposits all the rubbish from the estuary on the wreck site and the visibility can drop to very disappointing levels.

If you aim to dive in the middle of summer the boat traffic in and out of Salcombe Harbour is reminiscent of the Chiswick Flyover in the bad old days, so make sure that you have a large ‘A’ flag. In spite of all of this do not be put off. The Soudan is well worth diving, but because of the time factor a series of dives will be much more rewarding than just a single one.

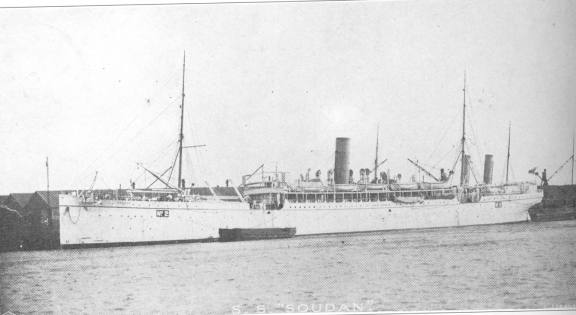

Incidentally, the photo of the Soudan is not to be taken as gospel. It is the right size, right shape, and it has the right name, but I have worries about the date. Extensive research has not come up with anything better but I am still not convinced that this is the right Soudan. I offer it more as a good illustration of what the Soudan probably looked like in the hope that it will add some enjoyment to your diving.

neville tustin says

Hi, some 30 yrs agoi used to fish off salcombe on a wreck known as the Bay Chattan off start point and with good landmarks on a decent day you could drop onto it with pinpoint accuracy.I have recently decided to make a visit to Salcombe which due to failing health will probably be my last. Many friends have passed on since the early 80s and I would like to put a wreath over her as a finaltribute but can find no bearings or other info listed any info would be gratefully received thanks.

Lalaine says

A wonderful job. Super helpful inomfartion.