Summer 1691. England was at war with her old enemy France, and the fleet were busy trying to lure the French and Dutch Navies out of the relative safety of the Channel Ports. The French however, knew when they were on to a good thing, and lay snug in their harbours whilst the English Fleet was battered by some of the worst summer storms anybody could remember. In late August, during a particularly bad gale, much of the Fleet retired to shelter in Torbay, and amongst those ships was the 90 gun second rate man of war, Coronation.

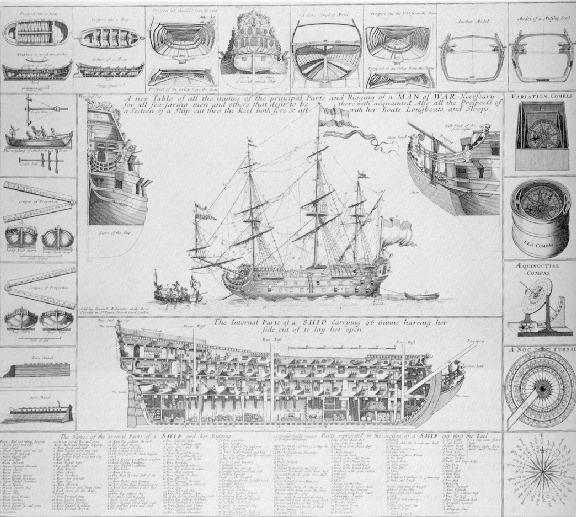

Launched in 1685 the Coronation was 140 feet long and weighed some 1366 tons. Commanded by Captain Charles Skelton, the Coronation should have had a ships complement of 660 officers and men, but due to manpower shortages it was unlikely that she was up to full strength and was probably managing with up to 100 men less than she needed. Whether this was to have some bearing on subsequent events I leave for the reader to decide.

After a couple of days the weather took a turn for the better and once more the Fleet, including the Coronation, sailed forth to blockade the French ports. Unfortunately on the first of September, when the Fleet was off Ushant, the weather turned extremely nasty and once more the ships had to turn tail, this time making for the safety of Plymouth Sound. The French must have laughed fit to burst, for the storms were accomplishing more than their own Navy had dreamed possible. Worse was to follow.

Most people know that Plymouth Sound provides one of the best natural harbours in England, well protected from southwesterly gales by a very effective breakwater. However in 1691 the breakwater had not even been thought of, and when the southwesterly gales blew, the safe haven of Plymouth Sound often turned into a raging deathtrap. Imagine that night of September 3 1691. Southwest winds of hurricane force blowing right across the Sound. The Fleet lashed by torrential rain and forced to take in all canvas. Communications with the flagship impossible. What to do? Anchor off Penlee or Rame Head and risk dragging onto a lee shore, or take a calculated risk and press on into the Sound. If you could miss Drakes Island and avoid being smashed onto the Hamoaze, you would be home and dry. If not disaster and a ruined career.

In the end some of the Fleet elected to anchor off Rame Head, and some like the Harwich, took the gamble and plunged into the maelstrom. She did not get far; in fact she didn’t even make the Sound but ripped onto the rocks near Maker Point. There was no hope for her, and she quickly smashed to pieces drowning 450 of her crew. Other ships followed the Harwich, some were successful, others foundered in the Hamoaze, ran aground at the Cattewater, or simply ran into each other. The carnage was fearful.

But what of the Coronation? Well she was still somewhere between Rame Head and Penlee Point, and what happened next is largely a matter for conjecture. All we do know for certain is that she was anchored somewhere between Rame and Penlee, apparently completely dismasted with only an ensign flying from her stern. A rainsquall obliterated her, and when visibility returned the Coronation had sunk killing Captain Skelton and all but twenty of his crew. We can only imagine that Skelton had decided to have a go at sailing into the Sound when he became dismasted. Perhaps he didn’t get his sails reefed in time. Whatever the cause he would have lost control of the vessel and found himself heading for the rocky shore at an alarming rate. In a vain effort to regain control he must have slipped his anchors, but the strain of bringing the Coronation up short in those murderous seas must have been her downfall. Maybe she took on too much water and foundered, or maybe she just started to break up. In any event, whatever the cause, down she went with well over 500 officers and men. That one night shocked the Nation. Over a thousand men were killed, and the damage done to the Navy was worse than a dozen sorties against the French. But the pressures on a country during a long war are many, and soon the shock of that terrible night receded, and by the turn of the century nine years later, I doubt anybody really remembered it.

For 276 years the Coronation lay undisturbed and unremembered. Unremembered that is until 1967, for then a ‘discovery’ was made that plunged the Coronation deep into controversy.

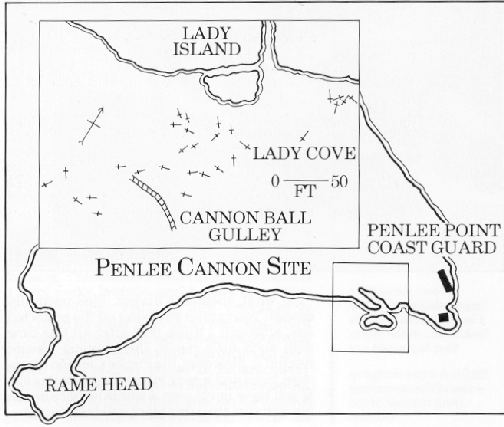

In 1967 George Sandford and Alan Down were diving together with Terry Harrison just off Penlee Point, when they came across some cannonballs, and then an iron cannon, another cannon and then lots of cannons. In all fifty cannons were later discovered in the area now known as the Penlee Cannon site.

Naturally George, Alan and Terry thought that they had found a major new wrecksite, and to their credit, they immediately called in the experts. After a lot of research it became apparent that the only ship capable of carrying this amount of cannons, to go down in the area with the Coronation. So could this be her final resting-place? Well yes and no.

In the next ten years or so, marine archeologists from just about everywhere had a go on the Penlee site. Large bronze wheels, thought to be steering pulleys, were found marked with the Admiralty’s arrow, as were lead scuppers, buttons, and pieces of rope. Over the years lots of different artifacts were discovered, but nothing that could positively identify the wreck was turned up. Even the cannons caused some problems, and the experts continually argued amongst themselves as to their proper identity.

Meanwhile the lads who had started it all had been doing a bit of research of their own. After collating a lot of the eyewitness reports, and reading the various state papers involved, they came to the conclusion that the Coronation must have foundered much further off Penlee Point, possibly in up to 100 feet of water. As time passed a lot of the experts seemed to agree but still opinion was sharply divided. Some just said that it MUST be the Coronation, others though that some other man of war had run ashore and ditched her cannons over the side in order to float off to safety.

Whilst the various arguments raged back and forth, other eyes had been scanning the state papers and sifting once more through the eyewitness accounts. In 1973 a small team under the direction of Peter McBride started to carry out a systematic search of an area some 1000 yards of Lady Cove using a proton magnetometer. The search was not easy, but after a frustrating four years in which hundreds of dives were done, McBride finally came across another cannon site in August of 1977. In a small area no more than 200 feet in length, he and his team found sixteen cannons and three anchors. They were delighted. But was it the Coronation? Five days after the initial discovery Peter McBride was finning over part of the wrecksite when he discovered a folded pewter plate jammed into a rock. After carefully easing the plate open he discovered that it contained a large crest bearing a coat of arms. Research in the Plymouth Museum showed that the crest belonged to the Lieutenant Governor of Plymouth, Sir John Skelton. Charles Skelton was his fifth son and of course also the Captain of the ill-fated Coronation. Surely this at last was proof positive. But was it? After all only sixteen cannons were found. The Coronation carried ninety. Where were the rest?

The arguments started all over again. McBride obtained a Wreck Protection order making it illegal for anybody else to dive on his wreck site, and carried on looking. To this day the Protection order is in force. Nothing else of any significance has been found, and hardly any diving now takes place.

So what of the Penlee Cannon Site? Well with fifty cannons there, and sixteen found on McBride’s site, people started to wonder if the two sites were not connected after all. They reasoned that if the Coronation had anchored where McBridge found his cannon site, then in the storm she could have broken up and her stern half been washed away to smash onto the rocks around Lady Cove. The next day there would have been lots of wreckage in the area as plenty of other ships came to grief that night, and so no one would have seen any reason to challenge the eyewitness accounts of the Coronation sinking somewhere between Rame Head and Penlee Point. Far fetched? Well maybe. But if you go out in a boat over the area on even a moderately rough day, you will soon see that it does not seem as ridiculous as it sounds. However I must confess that I am still far from being convinced, but then trying to puzzle these things out is surely one of the great attractions of wreck diving.

See the latest development on the official webite and contact the licence holders, Mark Pearce and ‘Ginge’ Crook if you want to dive the sites. They will usually try to accomodate you.

So what about the diving. Well naturally enough you cannot go diving on the protected wrecksite, and that protection also includes the Penlee site which is a shame as it is a very interesting dive. If you have never seen a whole lot of cannons lying in situ, then this place will fascinate you. The whole area is covered in a dense forest of kelp, the bottom being made up of sand and rock. The cannons, all between eight and twelve feet long, lie scattered all about, the deepest lying in about thirty five feet of water, the shallowest in about fifteen feet. They are quite easy to recognise even though they are covered with concretion and weeds. The trunnions are quite plain, as are the mussels. The kelp used to be periodically hacked down by the Fort Bovisand school who once used the site for instructional purposes. Closer inshore the kelp thins and lying in the sand are large mounds of what look like rust covered rocks. These are in fact groups of cannonballs, which have been covered in concretion.

Because of the varied bottom and thick kelp the fish life is quite prolific. The ever present wrasse like to hang about in case you disturb a tasty morsel, and medium sized lobster have been found closer inshore amidst the rocky gullies. Small free swimming conger eels can give you a start when you are poking about in the kelp, but their larger parents never seem to put in an appearance. So there you are. If you are not too keen on just looking at the cannons you will find that the whole area is very colourful, and a pleasant place to dive.

Read more about Admiral Shovell’s Treasure and Shipwreck in the Isles of Scilly, Peter McBride and Richard Larn’s book about the Coronation

norman says

Hi I am searching the history of the Skelton family I would be obliged if you could send me a description of the Skelton crest, on the pewter plate found at the wreck site,

Regards Norman

cHRIS jOHNSON says

I worked on the PENLEE site back in the early 70,s and we first discovered the 2 anchors snapped off SW of the cannon site which indicated the ship dragged on a SW gale. this conflcted with records stating Coranation lost on a SSE gale! I still have the original map of site that show position of anchors which we triangulated in from site to cliffs This was way before site was designated.regards chris johnson

Tristan says

For those interested we have a website now for the ongoing Coronation site work. If you have any information regarding the wreck we would be delighted to hear from you. Kind regards

http://www.coronationwreck.co.uk/

Mark Pearce says

Chris, please contact us with your info

Thanks

The Coronation Wreck Project

Karen Utley says

Am a descendant of Capt. Charles Skelton through his daughter, Sarah, who immigrated to the United States in the late 1690’s. Has any work been done on his lineage? Would appreciate any information or contact numbers for someone who could assist me.

Marjorie (Marnie) Skelton Stanley says

I am researching family lineage of the Skelton’s from Trelkeld, England. I have been going through documents and clippings from my Dad and have come across an article regarding the shipwreck of the Coronation, Captained by Charles Skelton. I am still trying to link to that family. The clipping was the from London Sunday Times and also has a picture of the Crest.