The SS. Great Britain, built in 1843 at the Great Western Docks in Bristol was a truly innovative vessel. Designed by the great I.K. Brunel, she was the worlds first iron hulled, steam powered, propeller driven ocean going ship, and was designed to serve the ever expanding trans-Atlantic luxury passenger trade. Originally conceived as a paddle steamer, the ships builders soon realized the enormous advantages of the new technology of screw propulsion and had her engines converted to power a sixteen foot iron propeller.

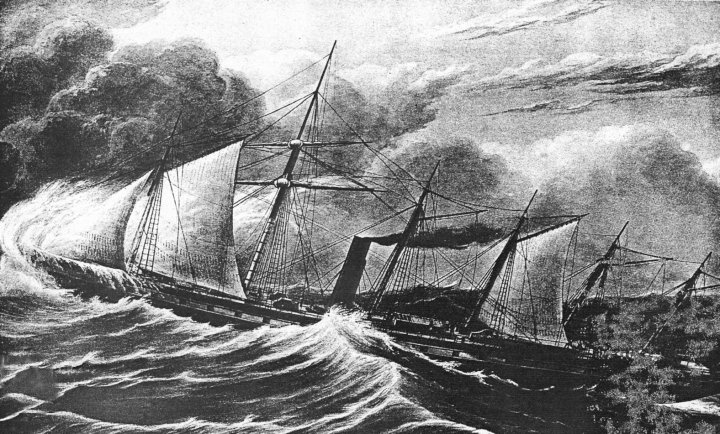

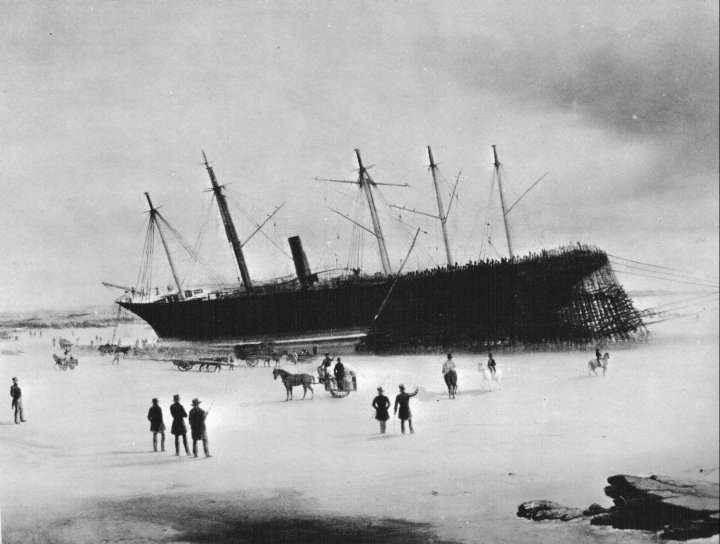

When the SS. Great Britain was launched she was the largest ship in the world weighing in at a colossal 1930 tons. Her maiden voyage to New York on 26 July 1845 was completed in an astounding fourteen days and showed her ability to do safe and speedy passages. Although she could take up to 252 passengers served by 130 crew, her voyages did not generate much money for her owners as they had miscalculated the demand for their services. When the Great Britain ran aground at Dundrum Bay in Northern Ireland in 1846, her engines were ruined and the expense of re-floating her so drained the finances of her owners that she was sold to Gibbs Bright and Company, who used her to great effect on the Australian run.

Gold had been recently discovered over there and so the Great Britain was remodelled as a fast luxury emigrant carrier and her accommodation was rebuilt to accommodate 750 passengers. Between 1855 and 1856 the British Government chartered the ship to transport troops to and from the Crimea War. Over 44000 troops were carried during the course of the conflict. Later she was again chartered to carry troops, this time to quell the Indian Mutiny. In 1861 she carried the very first English cricket team to tour Australia. The tour was a great success with England playing twelve games of which she won six, drew four and only lost two.

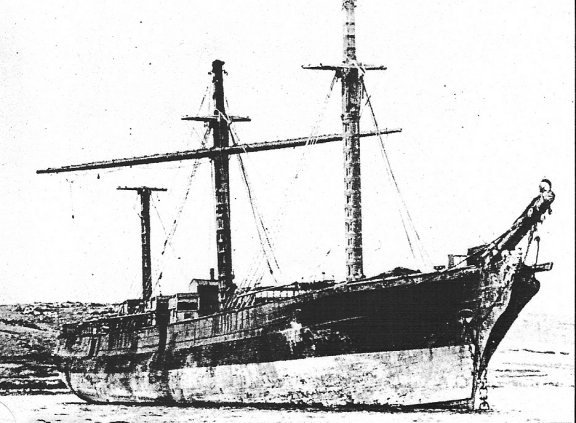

By the late 1870’s the SS. Great Britain was starting to show her age, and her owners could no longer keep their full registration as a passenger vessel. However because she had a sleek hull and low profile she could easily be converted to a three masted ‘clipper’ ship. With her engines removed and her spar deck torn off she was unrecognisable as the ship that had been launched all those years ago in 1843. Still she was still useful and could earn money for her owners and this she did by transporting coal from Wales to San Francisco. On her third trip she ran into trouble off Cape Horn and ran for the safety of Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands. Unfortunately for the Great Britain, the cost of repairing her was not deemed economic and so she was sold off for use as a coal and wool storage hulk and remained in Port Stanley.

Here she remained all through the First World War. Coal from her holds helped refuel H.M.S. Invincible and Inflexible before the decisive Battle of the Falklands in December 1914 which saw the destruction of the German battle cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. By 1938 the Great Britain’s hull was no longer watertight and she was towed a short distance from Port Stanley to Sparrow Cove where holes were cut in her hull and she was abandoned.

But the story doesn’t end there. People always loved this ship and recognised her historic significance. Unsuccessful salvage attempts were mounted in the 1930’s and 1960’s and during the Second World War bits of her were raffled off to raise money to build Spitfires. 1967 saw the start of what in the end turned out to be the successful attempt, when a naval architect called Dr. Ewan Corlett wrote to the Times about his ambition to bring the great ship back to Bristol. After many false starts plans were laid and surveys done but money remained the biggest problem. In the end a millionaire philanthropist called Jack Hayward (known popularly as ‘Union Jack’) said that ‘he would see the ship home’, and so finally things started to move.

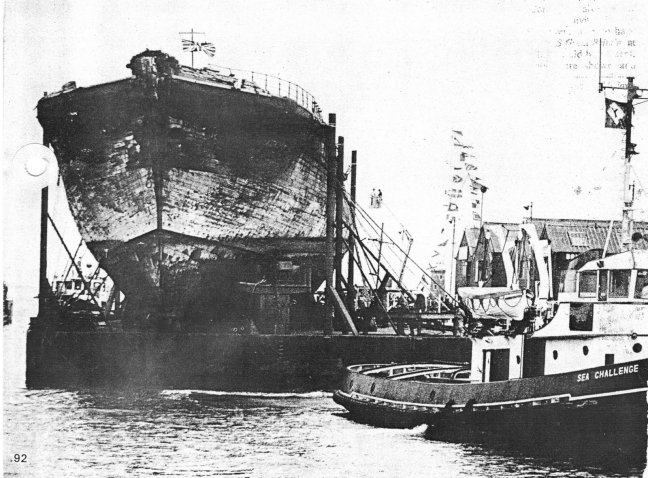

Unfortunately when the ship was fully surveyed prior to being towed home it was found that the hull was not strong enough to survive the journey. What to do? The salvors, Risdon Beasley came up with the idea of a submersible pontoon that could be placed under the ships hull then pumped out to lift the ship clear of the water. The pontoon would then effectively become a barge with the Great Britain stuck fast on top. On April 7 1970, most of the population of the Falkland Islands turned out to see the old ship start her epic voyage. At first the winds were savage and the sea exceedingly rough, but by the time the ship reached Montivideo all was calm.

As the tug Varius, commanded by Capt. Herzog, towed the barge with her precious cargo at a sedate five knots past Rio and onwards to Reciefe in Brazil the Atlantic Ocean beckoned. The weather remained kind to the Great Britain on the crossing and on June 18th she rounded Cape Finistere and was finally back in her home waters. On July 19th she triumphantly cruised up the Avon and slid into the dock where 127 years to the day, she was first launched by Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s Consort.

In 1970,the BBC’s Chronicle programme, did a great report on how the ship was saved.Just click the link below to see it.

Barry Atkin says

As a nation we owe a great debt to “Union Jack Hayward” and the other visionaries who had the courage and determination to repatriate the SS Great Britain to the UK for us all to continue to marvel at! Thankyou.

Mark Royall says

I wholeheartedly agree, Union Jack Hayward, and all the folks who did the work, to bring her back, I thank you. Great historic ship home where it belongs. Wonderful.

Richard Crowhurst says

Although without the generosity of Jack Hayward, “Uncle Jack”, advancing the money to pay for the salvage of the Great Britain, in my opinion this would never have happened without the passion and interest of one man in this great ship, Dr.Ewan Corlett. I had the priviledge of working with Dr.Corlett for a brief while, who was a highly intelligent, quiet and unassuming man who pioneered the understanding of ‘ship to ship’ and ‘ship to bank’ interaction in previously unexplainable and baffling collision cases. Basically what happened with the Great Britain is that, in (I think)1967 a British Antartic Survey ship called into Port Stanley. Dr.Corlett heard about this and asked the captain if he ever called in again to take some pictures of the wreck of the Great Britain. About 9 months later the BAS ship had to visit Port Stanley again, and the captain duly took a trip to look at the wreck of the Great Britain. The pictures that he took of her were then developed and sent onto Dr.Corlett. From these he wrote the famous letter to the Times in 1968 to say that the wreck was still very evident after 127 years, and should at the very least be documented and surveyed. Dr.Corlett then took a flight out to the Falklands to look at her first hand, and get some more pictures. When he went onboard the hull he realised that she was in a far better condition than he had imagined, and due to her hull being made of wrought iron and not mild steel (as are all ships for the last 100 years), that she had survived the ravages of time and corrosion extremely well. As a Naval Architect and with his inate experience in ship construction, he realised that she was strong enough to make one last voyage home to the UK. His knowledge in this great ship persuaded people that she was strong enough to be floated and salvaged, and set into motion the possibility of bringing her back, and the rest is history. But almost certainly that without his passion and interest, she would still be resting on the beach in Sparrow Cove, becoming part of the shallows in which she sat. So we owe the late Dr.Ewan Corlett a huge debt of gratitude, and he in my mind he is almost entirely responsible for rescueing her bringing her back. Other people played a lesser part, but were also important. For his services, he was made Honoury Naval Architect during the rescue project and her reconstruction in the Bristol dry dock where she was originally built.