The thing to remember about the sixties is that virtually nothing was known about underwater archaeology at all. Nobody really knew how wooden shipwrecks decomposed, and preserving artefacts was a very hit and miss affair. Most of the underwater archaeology sites were in the Mediterranean and they were mostly run by people who had never dived. Because of all this people stuck to outmoded practises and often made ludicrous statements about underwater shipwrecks in order to protect their positions and reputations.

By the time the Mary Rose project came along in 1965 there were a lot of so called experts, but not one who knew anything about the Tudor Navy. Various committees were formed, all convinced that they knew best, and all keeping their distance from each other in case they gave something away. Some included the Navy, and others were made up from local BSAC clubs. All tried to plot the others downfall, and of course none actually knew where the Mary Rose was. Enter Alexander Mckee arguing in essence that when the Royal George was levelled in the 1840’s,the subsequent explosions had not destroyed the Mary Rose. McKee passionately believed that she was largely intact, and that the mud would have by now buried her, and thus preserved her. Howls of derision greeted this announcement.

The opposition contended that the Royal George was nowhere near where McKee said it was, and that the Mary Rose, if she was anywhere, it was not there. McKee grew tired of all the shouting and decided to go back and look at all the old charts. He and the opposing factions ended up in the Hydrogpher’s office and compared charts. McKee had been using a copy of a 1784 chart called the Mackensie Survey and worked out his positions from that. The opposition had another chart, Sheringhams survey of Spit head 1841. This was a huge chart and when it was unrolled, there in the middle, more or less where McKee thought it should be, was a red cross with the words Royal George. Nearby was another cross with the legend Mary Rose. Unbelievably the Navy had completely over looked this obvious clue. X really did mark the spot. It was game set and match to McKee (who to his credit didn’t crow). The Navy and the rest more or less gracefully conceded, and McKee was once more in a position to direct the hunt for the Mary Rose.

Over the next few years a dedicated team of local divers and helpers with almost no money or resources sifted and dug away in the mud using an airlift, sonar scanned the whole area, and finally in 1970 unearthed a Tudor cannon that was the same as the one in Southsea Castle that was know to be of the same period. This proved beyond any doubt that this was indeed the site of the Mary Rose. Now the work to unearth the Mary Rose from her mud tomb could begin in earnest. Sport divers came from all over England to help, businesses donated funds and gear. The Prince of Wales became a patron and actually dived on the site, and a protection zone around the site allowed a diving barge to be stationed permanently over the wreck. Things were looking up, but there was still a huge amount of work to do.

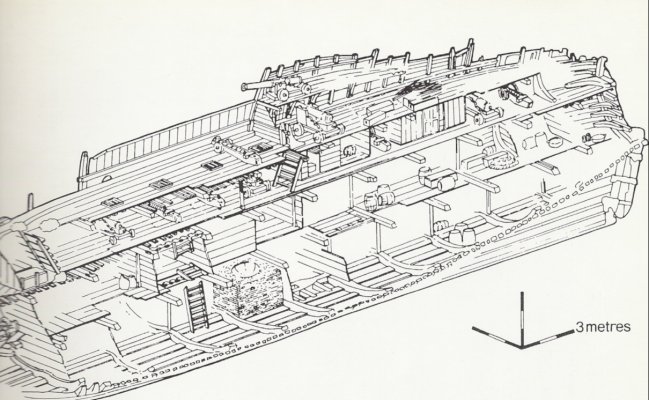

For a start, how much of the Mary Rose was still there? Over the next couple of years it emerged that most of one side of the wreck was still intact. In effect, over half of the wreck was still there, lying in the mud on her starboard side, remarkably well preserved. The mud had also preserved most of the ships equipment and personal remains. More guns were raised, long bows and arrows, stone moulds for casting lead shot, a shoe, a pocket sundial and a lantern were all amongst the early finds. But overshadowing all this was the sheer excitement of unearthing a ship that was last seen in 1545. The team were by now beginning to understand that the Mary Rose was more than just a shipwreck. She was an almost perfectly preserved Tudor time capsule.

One of the most frustrating problems, was that McKee and his team still were not sure what they were looking at. The Mary Rose was to some extent the missing link in ships architecture. No sooner had they settled on what they thought was what part of the ship when another discovery would seem to contradict it. All they had to go on was a very old painting and a model of what they thought it should look like. In the murky waters off Spit head it became increasingly difficult to identify each piece and fit it into the jigsaw. But slowly and patiently they did just that. Fighting storms, currents and poor visibility, month by weary month, year by year the team worked solidly on, and slowly and carefully unearthed the Mary Rose and her treasures, showing what life had been like on board all those centuries ago.

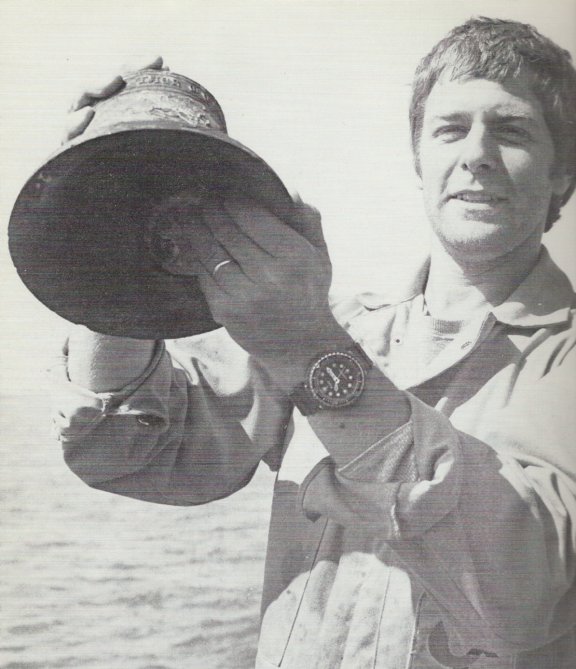

But it was not only treasures that they unearthed, but some of the crew as well. Skulls were found in the mud, and the bones of over a hundred and sixty crewmen were disinterred, some still with their leather jerkins. One, an officer, was found lying on his sword near the stern castle with his pockets still containing some gold coins. Finally in 1982, seventeen years after it all started the end was in sight. The ships bell dated 1510 had been found and the big lift to raise the Mary Rose had started to be organized. By this time the project had become ‘the’ thing to be involved in, in the underwater archaeology world, and had gained a life of its own. McKee was elbowed out of the way so that others could make their reputations, and a lot of big talk ended up with very little actually being done in preparation for the housing of the Mary Rose.

However before the lift could take place, a few hundred tons of ballast and thousands of firebricks from the oven hearth had to be removed. A cradle to support the wreck, whilst the lift was taking place, had to be manoeuvred into place and a million and one other things had to be organised before the operation was carried out before the watching gaze of millions glued to their television sets. Although an extremely complicated undertaking, the lift went off with only one hitch, a sickening lurch halfway through in which you could hear the sound of wood snapping. How much damage it did was glossed over and the Mary Rose was triumphantly carted off to Portsmouth Dockyard were she had started all those centuries ago.

But was she safe and sound? Well the answer is maybe. The artefacts certainly are, beautifully restored in a great museum. But the ship itself was left in a temporary berth with a bit of a botched conservation regime. The money to make a proper show home for her never really materialised, and she now languishes in a rather tatty shed. Conservation of such a fragile artefact as the Mary Rose requires a ton of money and dedicated expertise. One gets the feeling that the ship itself has become less important as the problems mount, and no one seems to have the will to push this project to a final, glorious conclusion like the Swedish did with the Vasa. However, carping aside, this is still a wonderful project, and a must see for any one interested in shipwrecks. One day it will be completed, I just hope I live to see it.

Maurice Young says

Speaking as one of the divers who helped find the Mary Rose and who now acts as a volunteer guide in the museum, I am appalled at the errors in the last part of the report. The conservation regime was never ‘botched’ nor has the wreck ever “languished in a rather tatty shed.” The phrase “nobody seems to have the will to push this project to a final, glorious conclusion like the Swedish did with the Vasa,” is both ridiculous and an insult to the Mary Rose Trust, the volunteers, fund raisers and all who took part in her recovery.

Oliver Beale says

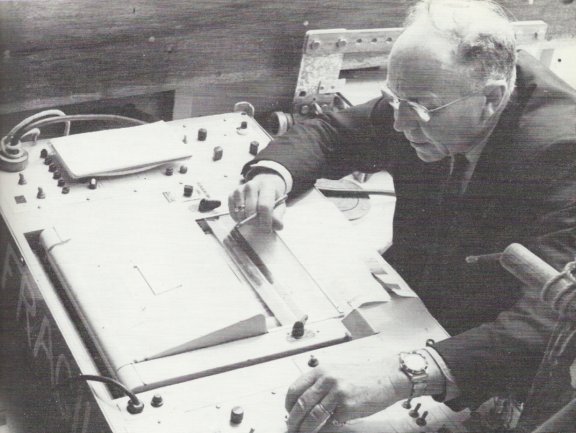

I believe the gentleman in the last but third image of the model maker is my granddad, George Beale. Working for Bassett-Lowke, he was commissioned to create the model for the museum.