One of the first things to catch the eye as you look out over Plymouth Sound is the breakwater. At first glance it might not seem a very remarkable structure, but without is Plymouth would not have a Naval base and without that, Plymouth would not be the thriving city that it is today. So although unremarkable, the breakwater has been very important in the development of Plymouth and it also has the distinction of being one of the very first free standing breakwaters ever built. But Plymouth did not always have a breakwater and although the Sound offered protection from the prevailing winds, southerly gales could often turn it into a deathtrap.

In 1690 the Admiralty decided to make Plymouth its major base in the South West and from then on the volume of shipping increased dramatically. Unfortunately so did the shipwrecks. Unprotected from southerly gales, wreck after wreck was driven across the Sound to smash onto the shore. The loss of life was appalling and hardly a winter’s month went by without the Sound becoming littered with the battered timbers of yet another shipwreck. In 1804, on one day alone, ten ships were wrecked in Deadman’s Bay and the regularity of such occurrences began to arouse public feeling. Although Plymothians were not adverse to their ‘Godsend’s they politely termed their wrecking activities, enough was plainly enough. Also since a large number of the wrecked ships belonged to the Admiralty, they were becoming increasingly embarrassed, as well as feeling financially squeezed. Obviously something would have to be done.

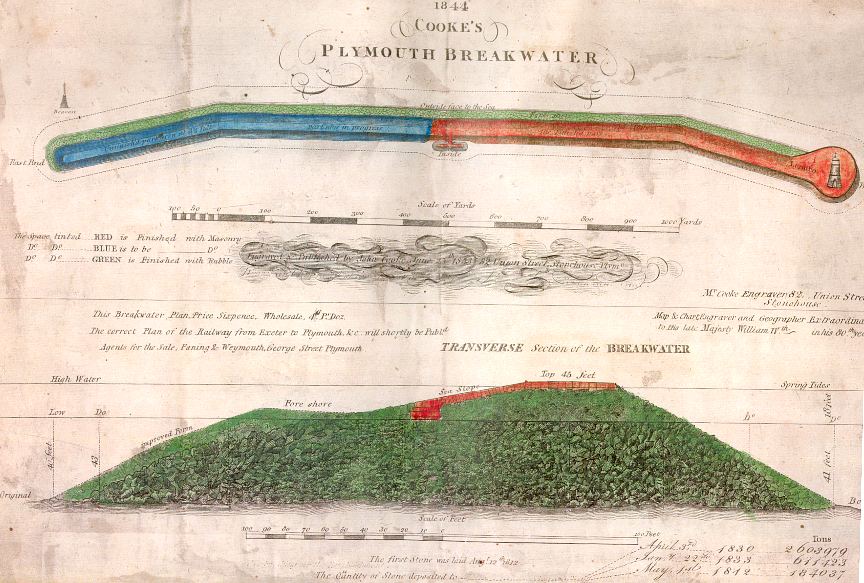

In 1806, the Admiralty commissioned a study into the building of a breakwater and after many delays the work was started in 1811. The building of the breakwater was entrusted to two engineers called Rennie and Whidbay. They decided to build the breakwater along the line of the Panther, Shovell and St.Carlos rocks, with two arms bending backwards to give better protection of the anchorage thus enclosed. Since the depths over the rocks was about 60ft, they also decided to build a solid wall that would end ten feet above the low water mark. The top would be thirty feet wide, with a base of 210ft and all in all the 3,000ft of wall was estimated to need about two million tons of stone. Most of the stone was to be in rough-hewn blocks weighing between one half and two tons, together with larger ten-ton blocks. The gaps would be filled in with rubble, and the whole lot allowed to settle and solidify.

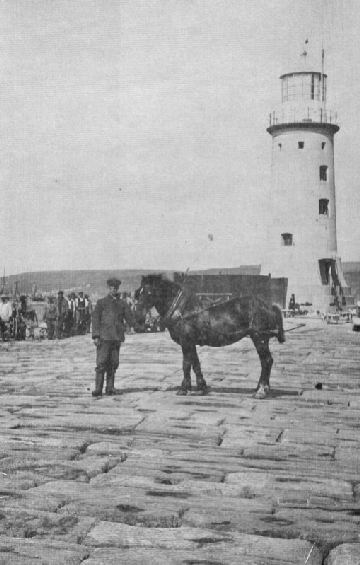

In order to produce such large quantities of stone,a new quarry was opened at nearby Oreston in the Plym estuary. The largest blocks were hauled to the quayside in railway trucks pulled by horses and then shunted straight onto the ships which had rails specially fitted into them. The smaller boats that carried the rubble, had special windlasses fitted, as well as tilting platforms and it only took them fifty minutes to moor, discharge the stone and then set off again. Not bad even by today’s standards.

By the end of 1812, nearly fifty thousand tons of rock had been sunk and some parts of the breakwater were already showing above the water. In 1815, Rennie and Widbay decided to raise the top of the breakwater by another ten feet and soon well over eleven thousand yards were showing above the water and already giving shipping some measure of protection.

The slope of the breakwater had been set at 1 in 3, but the severe storms of 1817 reduced this to 1 in 5 and washed large amounts of rock away. An enormous amount of work had to be done to reinstate the original gradient and it gave the engineers plenty to think about. In the end, after successive storms had once again altered the gradient, it was decided to let the sea determine the best gradient, which, in the end, turned out to be about 1 in 5. However to prevent further shifting, the outer wass was strengthened with granite blocks dovetailed to fit against one another. These were then cemented and bolted into place, the bolts being held firm by molten lead being poured into the boltholes. More rubble was then dumped to fill in the gaps and by about 1830 the whole structure had consolidated into an immovable breakwater. The top part being the most exposed was paved over with granite so that it gave virtually no resistance to the waves and by 1841 Plymouth’s breakwater was officially completed. However, the structure still needed rocks added to it regularly to keep it firm and by 1847 over three and a half million tons of rock had been dumped, and even today huge blocks, some weighing nearly one hundred tons, are periodically dropped into place to foil the ever probing sea.

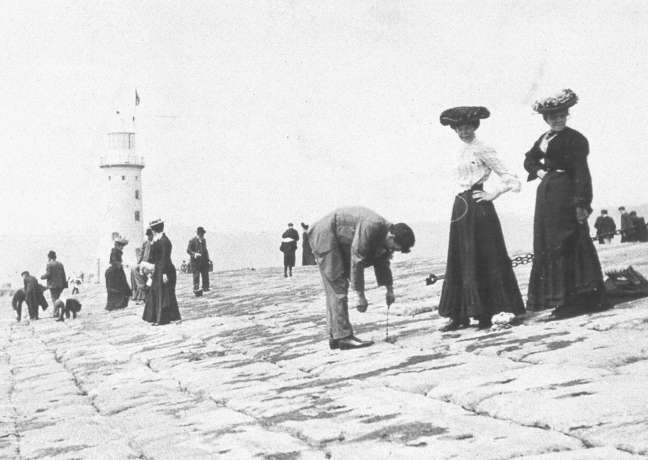

Of course as soon as the breakwater started to rise above the water, ships quite naturally started to wreck themselves on it. The merchants complained bitterly and in the end a lighthouse was erected at the western end of the breakwater, this being by far the most used of the two channels. For reasons of economy, the Bovisand end had a beacon. This consisted of a metal globe some six feet in diameter mounted on a pole so as to be some twenty feet above the high water mark. In an emergency, a shipwrecked sailor could climb up the pole and get into the globe to wait until help arrived. However even with its lighthouse and beacon, the breakwater still attracted ships like a moth to a flame. Most of the modern ships that struck the breakwater in the 19th century, like the Thetis or the Erin, went completely to pieces and have little or no trace of their passing. But in the period encompassing the two World Wars, many iron ships struck the breakwater and although some were successfully floated off, the remains of at least three ships and one aircraft still lie scattered on the seabed at the bottom of the breakwater.

The Yvonne, a steel barquentine of 1,000 tons, struck the breakwater in September 1920 and became a complete loss, as did the requisitioned trawler Abelard, which struck a mine of Christmas Eve 1914. These two wrecks have been fully described in previous Scenes, as has the Lancaster Bomber which crashed into the breakwater after a raid on the submarine bases at L’Orient in 1944.

The last shipwreck is situated about 200 yards from the breakwater light. Although marked as an obstruction on the chart, it is in fact the last resting place of the self propelled Hopper Barge No.42 which hit the breakwater in September 1913. All these wrecks and perhaps more, await the diver’s inspection, but don’t go away thinking that’s all the breakwater has to offer!

Most breakwaters are really elongated piers anchored to the land at one end. But Plymouth’s is a freestanding breakwater and in effect it constitutes one of the largest man made ‘reefs’ in the country. This ‘reef’ stretching down almost sixty feet in some places, provides home for a host of marine creatures and gives the diver well over a mile of varied sea bottom to explore. The west end, where the lighthouse is, has a very sandy bottom upon which a huge jumble of boulders lie. As you progress seawards, around the breakwater light, the rocks fall away very steeply to give the impression of a cliff. The currents can be quite strong, but if you pick your time carefully, you will find that lobsters and crabs abound on the seabed, as do dogfish and small ray. The middle part of the breakwater has more huge blocks, most of which were dropped about twenty years ago. These form an outer wall and are jumbled one on top of the other, so as to form large crevasses and deep holes. The fish absolutely swarm around these and if you want to find nearly all the different types of fish present in Plymouth, this is the place. Further out on the sand, at the base of the rocks, swim the pollock chasing the huge shoals of sand eels. Watching the pollock herding the sand eels into a suitable mass is an education in itself and an evening dive here to watch the pollock feeding is much better than watching even the best video.

Between the top of the breakwater proper and these rocks, lies a narrow channel. You cannot get a boat in, but a snorkel along this channel is a very rewarding experience, as you will be able to see masses of smaller fish and also plenty of wreckage that you most probably would not see when you are diving on the seaward side of the rocks. Further down towards the Bovisand end, the breakwater seems to flatten out. On the bottom the rocks are not as big and the seabed is more shingle than sand, with a bit more weed than elsewhere. Even so it is a very pleasant dive and with wreckage from the Yvonne scattered all over the area; it makes for a very interesting poke around. Round on the inside of the breakwater, things change considerably. Here there are no large rocks and the bottom is just muddy silt. The breakwater itself consists of fairly smooth granite and a lot of eelgrass grows there. Since the breakwater shelves quite steeply here, a swim along this part, through the eelgrass is very picturesque and if you stay at about twenty five feet you will be well away from the silt.

Further on the underwater terrain stays more or less the same until you reach the slipway below the lighthouse. Once again large jumbled rocks appear and the depth starts to increase to around fifty feet. There are a few large anchor chains lying around, some no doubt from the Hopper Barge and the thick weed seems to be a favourite place for small dogfish. The bottom drops quite steeply until, once again, you are on the sand, which is where we started from. So the breakwater really offers something quite unique. For once a man made object instead of interfering with nature, has actively encouraged, albeit accidentally, marine creatures to thrive in an almost perfect habitat. If you add in the wrecks, you end up with the equivalent of an underwater park and all this is right in the middle of one of Britain’s busiest ports.

Trailer for THE PLYMOUTH BREAKWATER, the great national undertaking. DVD

Jill page says

I found this most interesting having been on the Breakwater a few times in the mid 1950’s.

At the time I was in the Sea Ranger’s (no life jackets)… and we used row to the the Lighthouse to take parcels/ newspaper’s to the keeper’s.

I have a couple of old photo’s of us on the Breakwater.

Many thanks, Jill

Peter Miles says

One of my father’s favourite fishing spots. Also there used to be a Conger Eel fishing contest annually that went out to the wrecks at the breakwater. Thanks for posting this.

Gabriella Ghelardi says

Hi, would someone be able to tell me who wrote this and what year? I would like to reference this for my university essay.

Kind regards,

Gabriella

Hilary Bedson says

Family history is that my grandfather was the first Royal Naval diver and worked on the breakwater earning £1 day in the late 1800’s I would love to know more

Ray Cooke says

Back in the scorching summer of 1976, a temporary team of labourers (many between school and university) was hired by the Department of the Environment and deployed to Oreston for daily trips to the Breakwater, where many tonnes of concrete were mixed and poured into surface holes to repair erosion damage below. At the time there were said to be holes in the structure big enough to park a bus in. Basking sharks were regularly spotted off the Breakwater during that summer.

Jonathan Mumford says

I have been told that my Grandfather ,Fred Mumford, worked on the beacon, presumably a replacement, when he was apprenticed to a blacksmith on Oreston c1910. When the beacon was erected he went out to the Breakwater to finish off the smith’s work. I have a postcard of the beacon which shows it being made at the smithy. Jo Mumford

Kit Batten says

Hi!

Does anyone know the whereabouts of the plan by Cooke illustrated above? Many thanks.

Contact

KitTheMap@aol.com