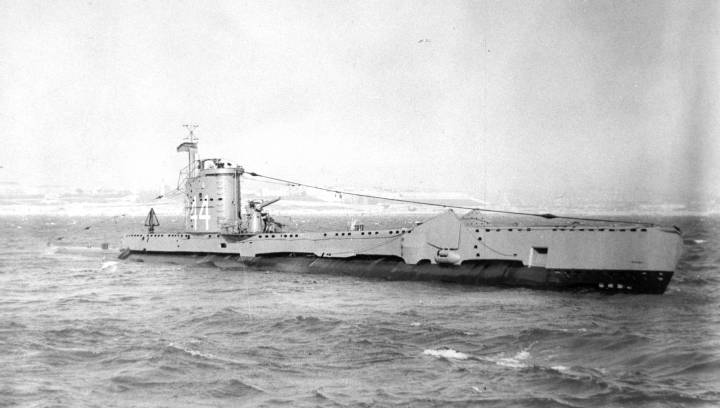

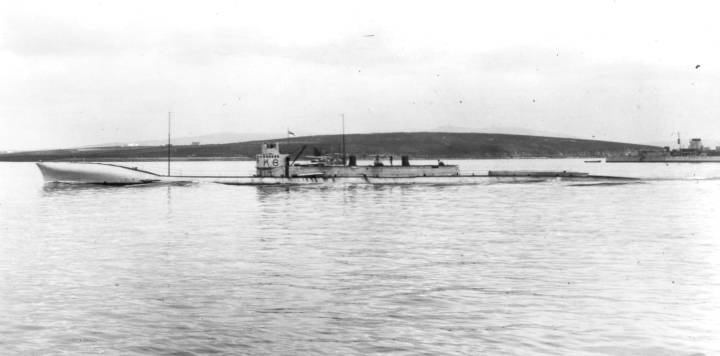

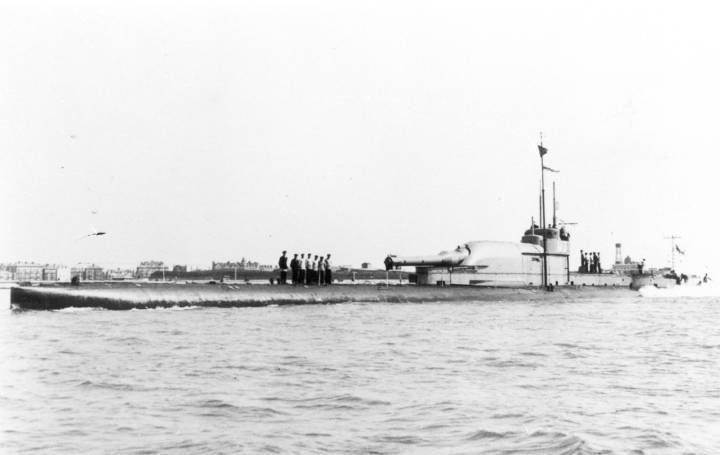

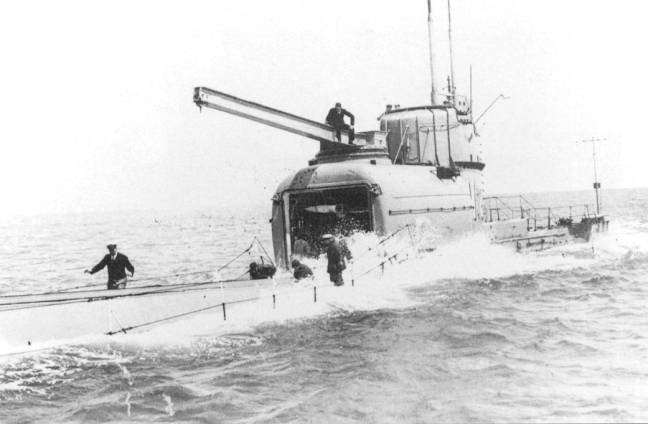

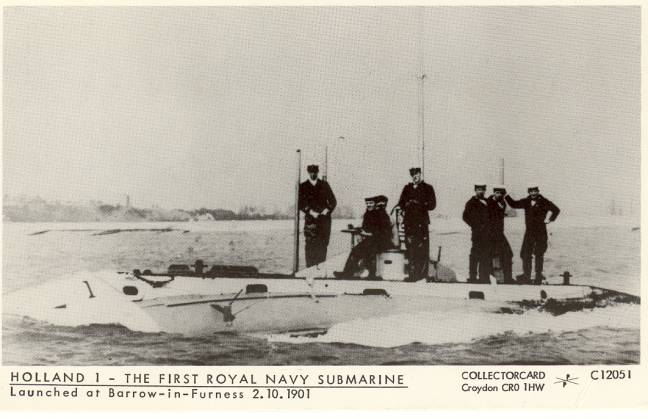

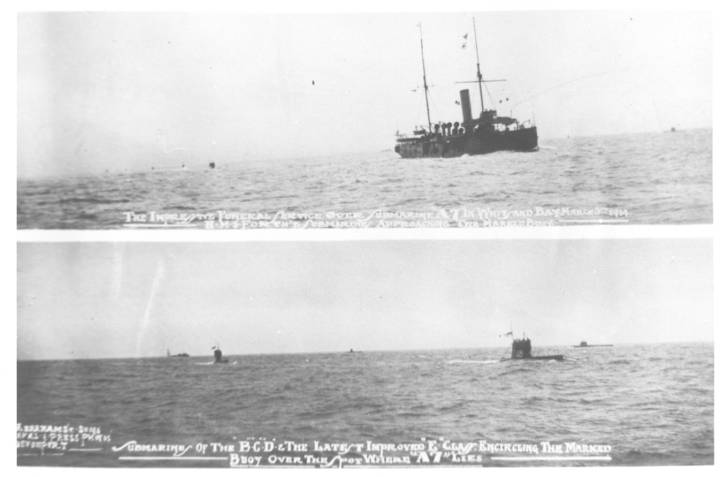

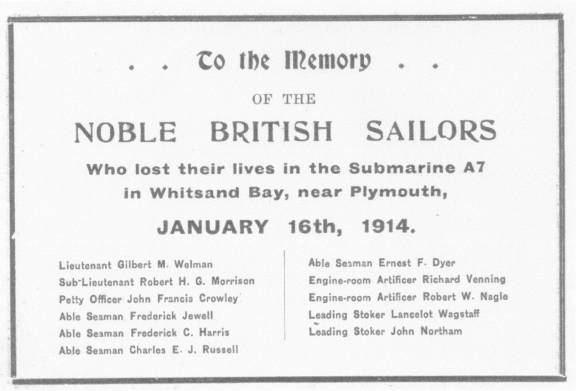

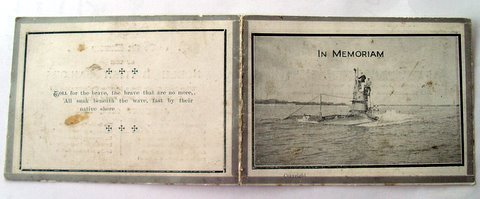

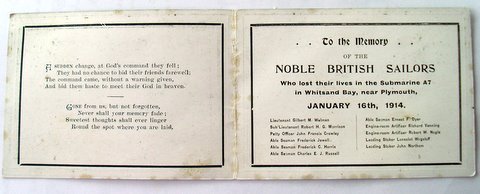

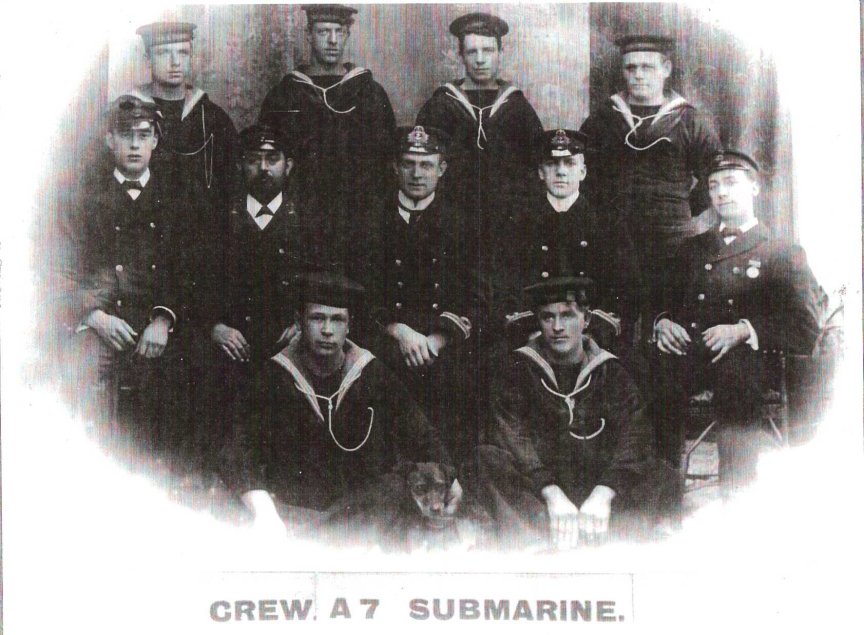

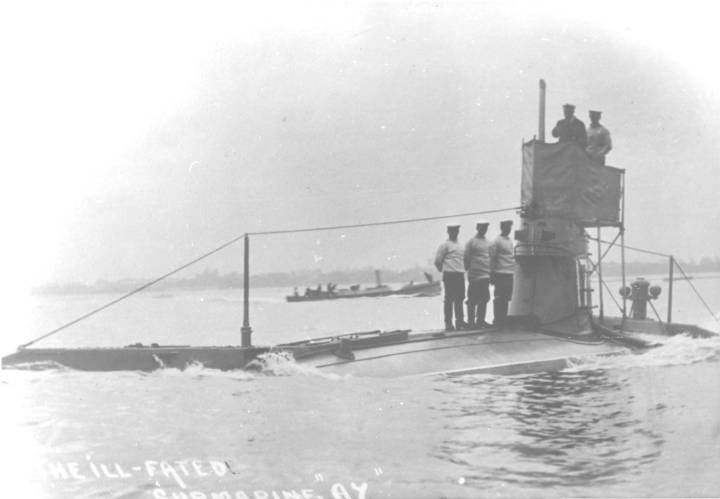

On the morning of the 16th January 1914, the submarine A7 was exercising in Whitsands Bay. She dived to carry out a mock attack on her escorts and failed to resurface. Her crew of eleven officers and men were never seen again.

The A7’s sinking was the latest in a long lie of accidents to afflict this class of submarine, and there had been at least fifty eight deaths in the run up to the outbreak of the First World War.

The loss of the A7 caused a storm of protest, not only from the general public, but in Parliament as well. Many MPs asked why these ‘Coffin Ships’ were still allowed to operate when they were so obviously obsolete and unfit for duty.

The submarine, once seen as an unwanted oddity, was now seen as a threat to the established order, and the Royal Navy made many mistakes as it tried to embrace the huge changes in tactics that were being forced upon it by the looming reality of global warfare.

The A7 was one of those mistakes.

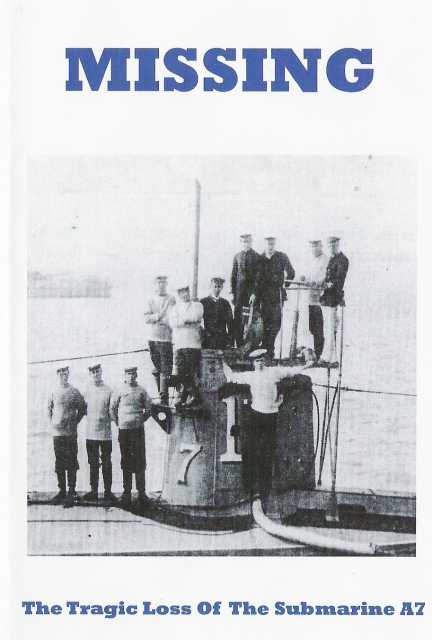

You can watch the full version of the Missing documentary below

Watch “Missing”, the full length Submarine A7 documentary

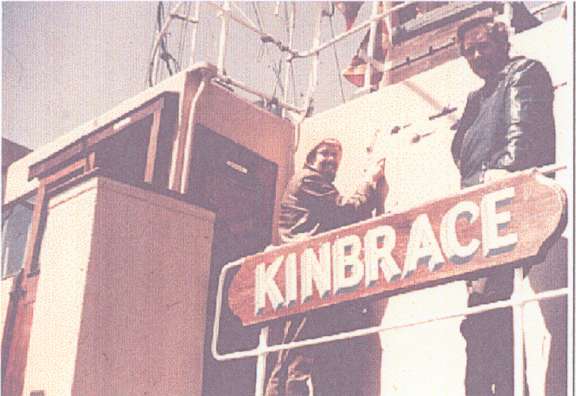

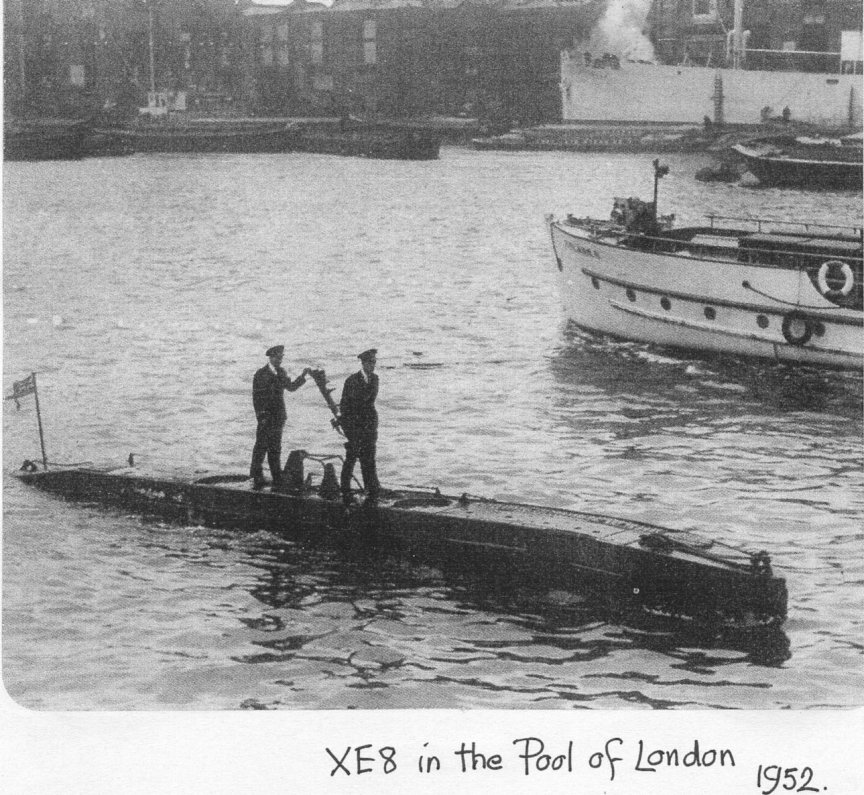

![The Captain ofHMS Kinbrace [left] standing next to the aide of the C in C Portsmouth and the Conunander in Chell [third from left] discussing the lift of HM Submarine XE8. The Captain ofHMS Kinbrace [left] standing next to the aide of the C in C Portsmouth and the Conunander in Chell [third from left] discussing the lift of HM Submarine XE8.](https://www.submerged.co.uk/wp-content/gfx/x/xcraft%201%20big.jpg)