review of this book

HMS. Goliath – William Earnest Wood

I am always amazed at how the small churchyards in the villages of Devon and Cornwall can yield so many wreck stories, many of which have happened hundreds of miles away on a foreign shore.

Thurlestone Church in Devon has one such story. In the small churchyard is the grave of Elizabeth, the wife of William Earnest Wood a Petty Officer Stoker who lost his life in the Dardenelles aboard H.M.S. Goliath in May 13th, 1915.

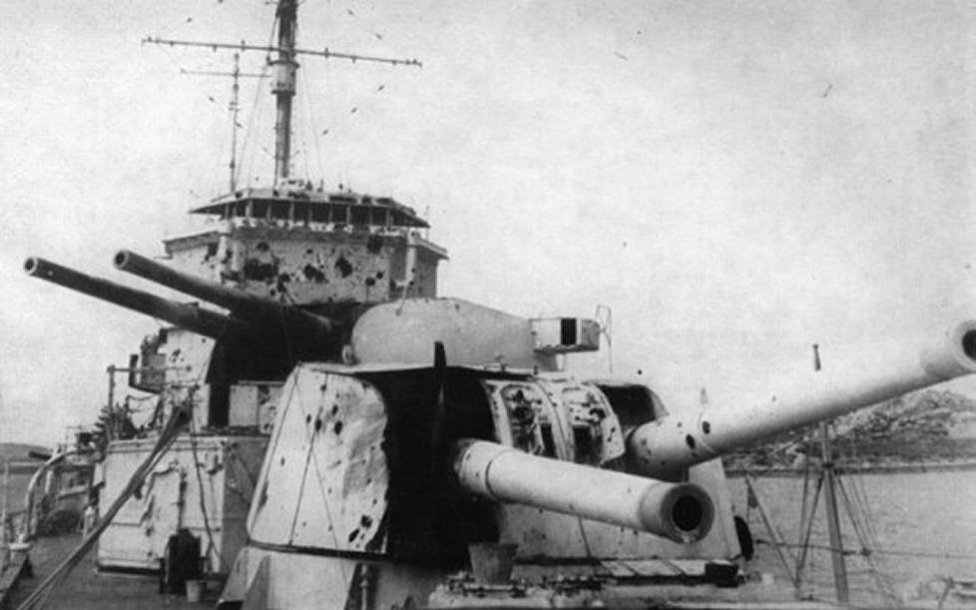

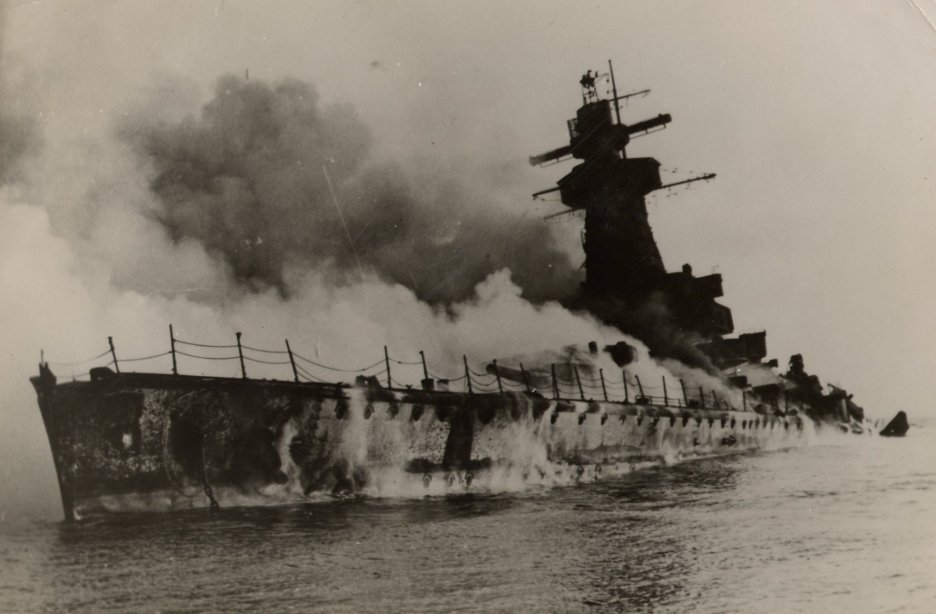

HMS Goliath was one of the six Canopus-class pre-dreadnought battleships built by the Royal Navy in the late 19th century. Commissioned in 1900, she served in the Far East on the China Station until 1905, at which time she joined the Mediterranean Fleet. In 1906, she was attached to the Channel Fleet and about 1909 was put into the reserve, at Portsmouth.

When the First World War broke out in August 1914, Goliath was returned to full commission and assigned to the 8th Battle Squadron, Channel Fleet, operating out of Devonport. She was sent to Loch Ewe as guard ship to defend the Grand Fleet anchorage and then covered the landing of the Plymouth Marine Battalion at Ostend, Belgium, on 25 August 1914.

Goliath transferred to the East Indies Station on 20 September to support cruisers on convoy duty in the Middle East, escorting an Indian convoy to the Persian Gulf and German East Africa until October. She then took part in the blockade of the German light cruiser SMS Königsberg in the Rufiji River until November, during which crew member Commander Henry Peel Ritchie won the Victoria Cross.

On 25 March 1915, Goliath was ordered to the Dardanelles to participate in the campaign.Commanded by Captain Thomas Lawrie Shelford, Goliath was part of the Allied fleet supporting the Allied Army during the landing at Cape Helles on 25 April. She sustained some damage from the gunfire of the Ottoman Turkish forts and shore batteries, and then again supported Allied troops ashore during the First Battle of Krithia that day. She later went on to cover the evacuation on 26 April.

On the night of 12–13 May, Goliath was anchored in Morto Bay off Cape Helles, along with H.M.S. Cornwallis and a screen of five destroyers, in foggy conditions. Around 01:00 on 13 May, the Turkish torpedo boat destroyer Muâvenet-i Millîye, which was manned by a combined German and Turkish crew, eluded the destroyers Beagle and Bulldog and closed on the battleships. Muâvenet-i Millîye fired two torpedoes which struck Goliath almost simultaneously abreast her fore turret and abeam the fore funnel, causing a massive explosion. Goliath began to capsize almost immediately, and was lying on her beam ends when a third torpedo struck near her after turret She then rolled over completely and began to sink by the bows, taking 570 of the 700-strong crew to the bottom, including her commanding officer, Captain Thomas Lawrie Shelford and William Earnest Wood.

Although sighted and fired on after the first torpedo hit, Muâvenet-i Millîye escaped unscathed. For sinking Goliath, Turkish Captain Ahmet Saffet Bey was promoted to rank of Major and the German captain of Muâvenet-i Millîye, Kapitänleutnant Rudolph Firle, was awarded the Iron Cross 1st Class as well as Austro-Hungarian and Turkish decorations.

Admiralty 10th April 1915

VC citation

The King has been graciously pleased to approve of the grant of the Victoria Cross to Commander Henry Peel Ritchie Royal Navy for the conscious act of bravery specified below –

For most conspicuous bravery on the 28th November 1914 when in command of the searching and demolition operations at Dar-es-Salaam East Africa Though severely wounded several times his fortitude and resolution enabled him to continue to do his duty inspiring all by his example until at his eighth wound he became unconscious The interval between his first and last severe wound was between twenty and twenty five minutes.

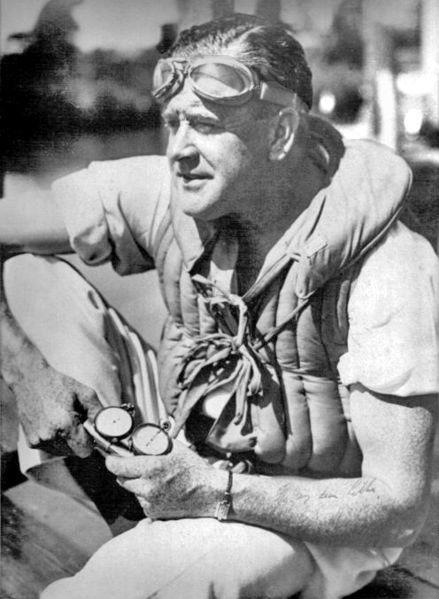

Lawrence of Arabia at R.A.F. Mountbatten, Plymouth

Just about everybody has seen the film Lawrence of Arabia, which more or less correctly portrays T.E. Lawrence rushing around the dessert on a camel inspiring various Arab tribes to fight on behalf of the British in the First World War. At the end of the film the impression is given that shortly after the War ended, Lawrence returned to England and was killed in a motor bike accident. His accidental death is true, but it happened some 17 years after he returned from the War, and in the intervening time he had another, little known career in the Marine Branch of the R.A.F. where he was instrumental in developing the R.A.F’s fast rescue boats, which in the end saved some 13000 lives.

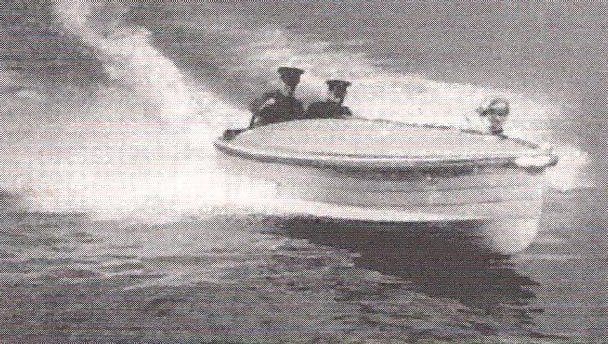

In 1925 Lawrence joined the Marine Branch at R.A.F. Mountbatten in Plymouth under the assumed name of T.E. Shaw. The Base Commander, was Wing Commander Sydney Smith, a long time friend of Lawrence who gave him a job working with a civilian Hubert Scott-Paine to develop and test what later became the R.A.F’s famous ‘crash boats’ immortalized in the book and film, The Sea Shall Not Have Them, which was also their motto. Lawrence was deeply interested in this project as he had witnessed at first hand a sea plane crash in 1931 and was horrified at the slowness of the boats sent out to the scene, which meant that all of the crew drowned long before any of the rescue boats arrived.

All of these boats were based on Navy boats which had to do a completely different job and were obviously so inadequate (Lawrence called them ‘dull stupid heavy motorboats’) that Lawrence lobbied the Station C.O. to replace their slow boats with faster planning boats. These were quite rare and new-fangled, but Lawrence had had some experience of them whilst assisting with the 1929 Schneider Trophy. The tender to the yacht that Lawrence had stayed on at that time was a Biscayne Baby Launch which although fast, had temperamental engines which Lawrence showed a remarkable aptitude to keep running, so the owner gave the Launch to him as a present.

Hubert Scott-Paine was one of the most famous people in the world of powerboat racing and marine aviation. He had managed the Supermarine factory in Southampton and in hiring R.J. Mitchell (of Spitfire fame) he managed to win the Schneider Trophy in 1922. Scott-Paine then set up the British Powerboat Company which by 1931 had built the fastest boat in the world, Miss England 11 which set a new world water speed record of 98.7 m.p.h. and later raised this to 111m.p.h. While all this was going on Scott-Paine had also made an offer to build a 35ft planning launch for the R.A.F. The man dealing with this for the R.A.F. was Flight Lt. W.E.G. Beauforte-Greenwood and it was he who suggested to Scott-Paine that Lawrence would be the ideal person to conduct the trials and development of these boats. The R.A.F. initially wanted 40ft boats but Scott-Paine preferred a length of 35ft. in the end a compromise was made and they started with a 37ft 6 inch craft. The result was the rather doubtful sounding 200 Class Seaplane Tender which was in fact a very fast motor launch. constructed of diagonally planked mahogany, a single layer on her topside with the rest of the hull made of a double layer to give strength. She was powered by two 100 HP Masons engines which gave her a top speed of some 36 knots.

The testing of this boat took up most of Lawrence’s time at Mount Batten because a lot of the work was in unknown territory and the engines had to be made to be reliable a sustained high speeds. Lawrence was self-taught and by now well respected for his marine knowledge and practical application. He was invited to write the official handbook for the RAF ST 200-class speedboats and the handbook today remains perhaps the most concise and instructive technical manual ever published. It was still in use until well after World War II. In 1933 Lawrence left Mount Batten to take up his duties at the RAF Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment at RAF Felixstowe. Two years later he was killed in a motorbike accident near his home at Clouds Hill. You can see one of the boats that Lawrence worked on at the R.A.F. Museum in Hendon.

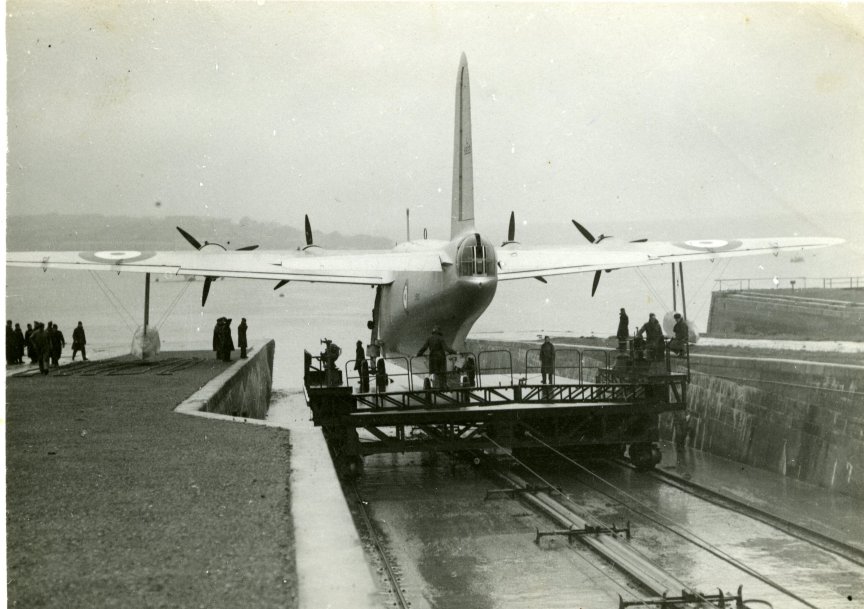

The Sunderland Flying Boats of Plymouth

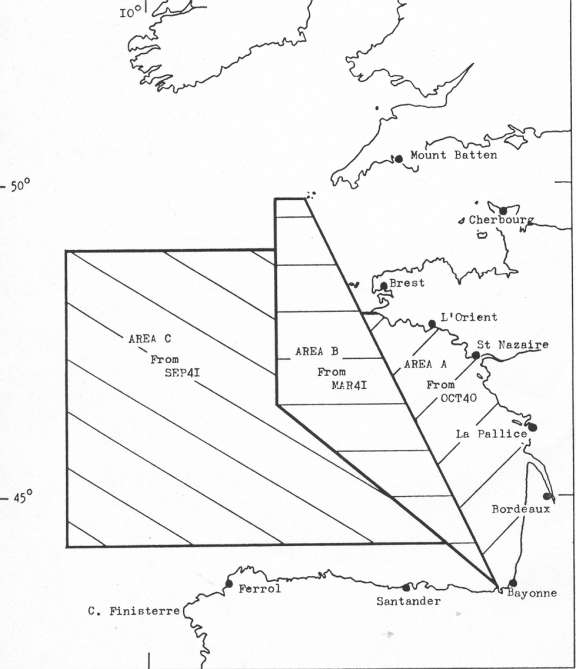

During the Second World War, Mountbatten was home to No. 10 Squadron Royal Australian Air force, and those now deserted hangars hummed with activity as they serviced , the needs of the Squadron’s aircraft, Sunderland flying boats. Named after Admiral Batten a Civil War Governor of the ‘headland and tower’, the history of Mountbatten goes back to the Great War when in 1917 R.N.A.S. Cattewater Seaplane Station was opened as part of a comprehensive chain of South West bases, who’s main task was to bomb U. boats in the Western Approaches. After the Great War ended most of the South Western chain of bases were disbanded, but R.N .A.S Cattewater stayed in operation if only as a storage and cadre unit. However as the decade wore on a modest expansion in the role of the seaplane saw Mountbatten return to full operation, and on October 1 1928 Cattewater Station was renamed Mountbatten and that is the way things have stayed up till the present day.

During the early thirties life at Mountbatten was pleasant and peaceful. Training flights and the odd cruise to the Continent or the Mediterranean relieved the boredom. However as the war in Europe became increasingly apparent 204 Squadron were re-equipped with Mountbatten’s first Sunderlands in June 1939, and soon became responsible for patrolling the Western Approaches where if hostilities broke out they would once more hunt down the U. boats in one of their favourite killing grounds. When War was finally declared, 204 Squadron had six Sunderlands fully operational, and on 4 September they launched their first operational anti-submarine patrol into a grey Plymouth dawn. After nine hours of uneventful patrolling the crew brought the Sunderland safely back only to be shot at by the local anti-aircraft battery, who were thankfully long on determination, but short on eyesight.

On 1 April 1940, 204 Squadron moved to Sullom Voe in the Shetlandsand the Australians moved in, in the shape of 10 Squadron Royal Australian Airforce. They were to stay for the rest of the war hunting submarines with a brief departure to Wales during the height of the Plymouth Blitz. This made life impossible for the Sunderland crews, who with Plymouth Sound so jammed with shipping could hardly take off without hitting either wandering merchant ships or Naval craft rushing around the Sound trying to avoid being straffed by enemy planes. As the war ended many of the Squadron’s Australian personnel were repatriated, and on 5 November 1945 10 Squadron left for good and Mountbatten was transferred from Coastal Command to Maintenance Command. It was the end of its days as a flying boat station.

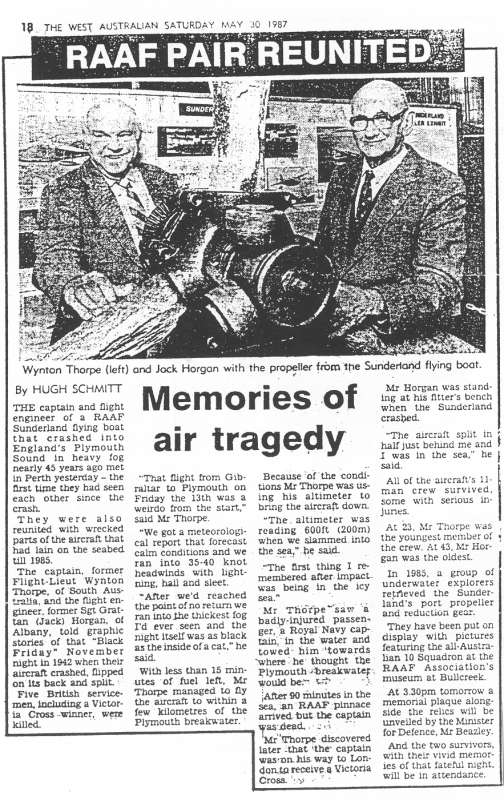

Besides hunting U. boats and patrolling the Western Approaches the Sunder lands were also used for transporting personnel to bases as far away as Gibraltar. It was on such a mission that disaster struck for the flying boat captained by Flight Lieutenant Wynton Thorpe. The flight from Gibraltar to Plymouth during November 1942 got off to a bad start right from the beginning. For one thing it was Friday 13, and for another the meteorologists managed to get the weather completely wrong. As Wynton Thorpe, his eleven man crew and five passengers left Gibraltar the forecast was for calm conditions. Almost at once they ran into forty knot headwinds, with lightning and hail thrown in for good measure.

As the flying boat bucked and swooped its way towards England the weather increased in ferocity, but by then the boat was at the point of no return. All Wynton Thorpe and his crew could do now was tough it out. At last the weather changed. No more hail and sleet, just thick, black fog. Thorpe later said that “it was the thickest fog he had ever seen” and “that the night was as black as the inside of a cat”. With great skill Wynton Thorpe managed to fly the aircraft to within a few miles of the Plymouth Breakwater, but the fog was so bad he was unsure of where he was or how high he might be above the sea.

With less than fifteen minutes of fuel left he decided to try for a landing. Because the conditions were so bad, he had to rely completely on his altimeter to bring the seaplane down. He was completely blind. When the altimeter was still reading 600 feet the Sunderland slammed into the water. The shock of the impact devastated the aircraft and split it right in half throwing Thorpe straight into the sea. Almost at once he saw one of the passengers, a Naval Captain, lying in the water and started to tow him to where he thought the Breakwater was. They remained in the sea for over ninety minutes before a rescue pinnance finally found them. Alas the bravery and determination of Wynton Thorpe was to no avail. The Naval Captain was dead and Thorpe near collapse. In the end all eleven crew were saved although most sustained serious injuries. None of the five passengers survived. Later, after he had recovered, Wynton Thorpe was to wonder at the irony of his lucky escape. The Naval Captain, that he had tried so hard to rescue, had only been on board so that he could come to London to receive the highest award of all, the Victoria Cross. What a terrible price to pay for the Nation’s gratitude.

Today all this would just be a fading memory but for a diver called Neil Griffin. He and his mates used to dive around the Breakwater quite a bit and one day they were diving on the inside area between the Breakwater Fort and the Lighthouse when Neil found a large piece of aluminium framing. Now the bottom here is very silty mud, and by the time he had completed his investigation of the metal frame he had stirred up the silt so much that he could not see a thing and so decided to call it a day and surfaced. Unfortunately the boat was drifting, and by the time he got picked up and was back on board he really had very little idea of where he had actually been diving.

Still Neil is nothing if not determined, and over the next few months he searched and searched (talk about positive thinking) and finally found the remains of what he thought were two Sunderlands. One was really mangled and spread over quite a large area, but the other was recognisable as two bits of one plane. Over several dives Neil explored this aircraft and after finding the port propellor and reduction gear, decided to raise these along with some other artefacts and offer them to the Australian Airforce Museum.

Unfortunately Neil’s position finding was not as accurate as he thought it was, and it took him some time to relocate the sunken Sunderland. By this time the weather had deteriorated and silt had moved over various parts of the wreckage making orientation underwater somewhat difficult. After a lot of false starts Neil finally relocated the Sunderland’s propellor and the reduction gear, and in a blaze of organization raised the lot and carted it off to R.A.F. Mountbatten for safe keeping

Now if you or I had done this a local museum would probably have told us to go away and take our rubbish with us, but not the Australians. They were very keen to have the propellor and reduction gear for display at the R.A.A.F.’s Association’s Museum at Bull Creek near Perth. After the ground engineers at Mountbatten had tidied up the prop and crated it up, off it was shipped to Australia, and that is where the best bit of this story comes in. Still living in Australia were Wynton Thorpe and his flight engineer on that fateful day Jack Horgan. When the R.A.A.F. Association told them of Neil’s find they were dumfounded. They had not seen each other for over forty years and so the Association invited them down to Perth to be reunited with each other, and the remains of their once proud Sunderland flying boat. You can imagine their emotion and their vivid memories of that dreadful day, and of all their lost comrades in 10 Squadron.

On May 31 1987 they stood alongside the Australian Minister for Defence and unveiled a memorial plaque at the Bull Creek Museum alongside the Blades of their old Sunderland. For the two veteran survivors it was a vindication of their’s and their comrades committment and sacrifice all those years ago. For Neil, unfortunately only in there spirit, it was a wonderful moment. All the effort he had put in was amply rewarded by the gratitude of the old flyers and the Royal Australian Airforce. He had discovered the wreck and returned it back to its rightful owners. Not many of us will ever get a chance to do that, especially with something that has already passed into the history books.

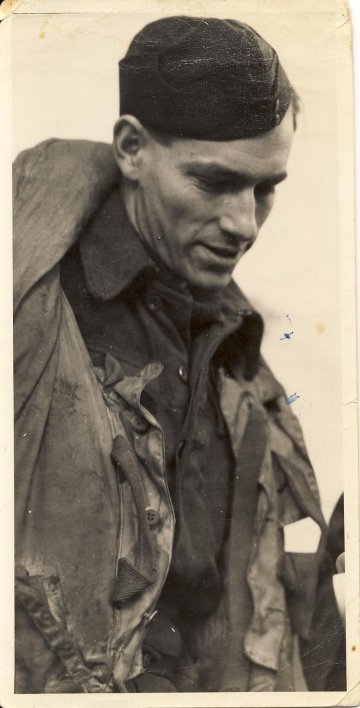

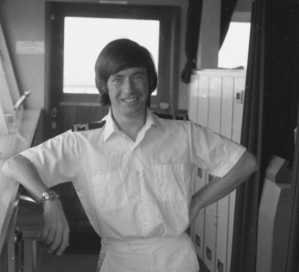

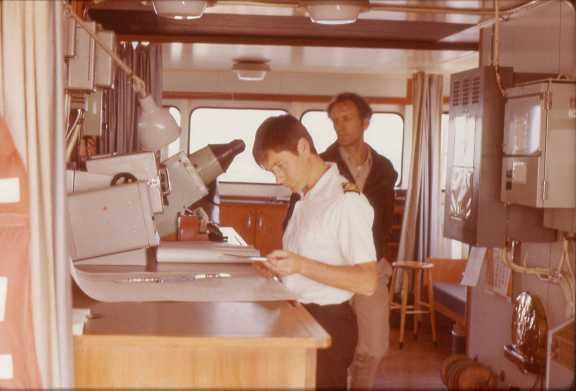

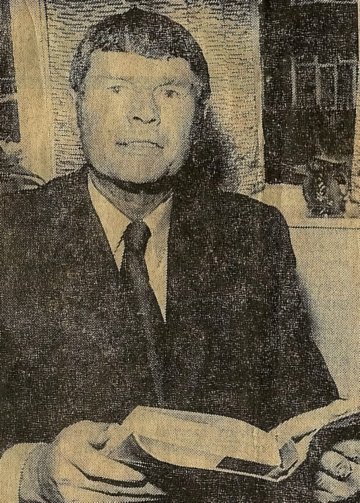

Squadron Leader Flight Sergeant Gordon Craig

I am very grateful to Helen Craig for the following photos of her father Squadron Leader Flight Sergeant Gordon Craig. He flew with 10 Squadron on the Sunderland flying boats out of Plymouth, hunting for submarines.

He told her many stories of landing in the cold waters of Plymouth Sound, limping into port with all the crew up on one of the wings to keep the plane upright and floating until it reached its slip. Sadly he passed away in 2006 aged 83.

My father was killed in WW2. He was a Flight Engineer (aka ‘cannon fodder’ – a rear gunner) in the 10th.

Three weeks after I was born, in February 1942, he was sent to join his squadron in Mount Batten. His plane was shot down over the Bay of Biscay in September of the following year and he never had leave back to Australia. He was 23 years old and my mother was a widow at 20. I know that Sunderlands, because they could fly low, below the radar, frequently were able to pick up survivors from other planes and his plane had been mentioned in dispatches only the previous week for doing this. Unusually, no survivors or even any wreckage of DV969, were ever found. I have been to the War Memorial in Canberra and read in the log book the handwritten exchange between my father’s plane, at that time flying over the Bay of Biscay, and the base, where the pilot reports a number of Junker 88s coming towards them. There was no further entry.

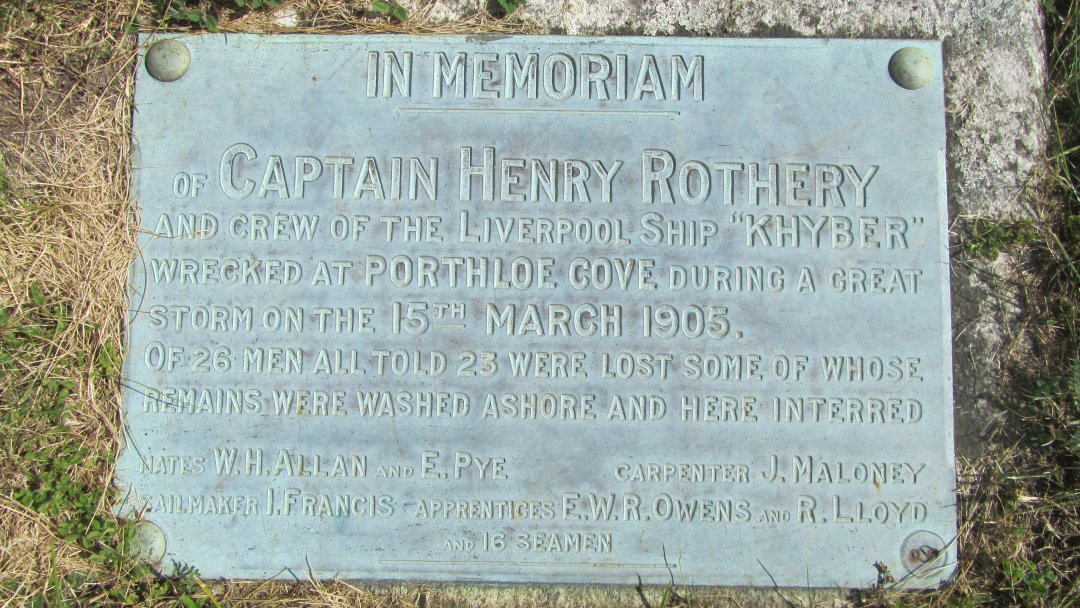

The Wreck of the Kyber

The Kyber was an iron windjammer of 1967 tons, launched on Merseyside in 1880 for the Indian trade of the Brocklebank Shipping Line. In 1899 she was sold to the Calgate Shipping Company of liverpool and it was under this management that she embarked on what was to be her last voyage.On September 16th 1904 the Kyber was at the mouth of the Yarra River, Melbourne Australia, with orders to sail for Queenstown in Ireland with a cargo of 3000 tons of Victorian wheat. The voyage went well and on March 1905 she was 138 days out from Melbourne approaching the Cornish coast, when she was spotted by the lighthouse keepers on the Wolf Rock running before a freshening south westerly wind on course for the Lizard. However, as the day wore on the weather worsened with the wind rising to a near gale forcing the Kyber inexorably into Mounts Bay, which is between Lands End and the Lizard.

The men at the Coast Guard station were joined by the Cox’n of the Porthleven lifeboat who had seen the Kyber wallowing in heavy seas too far to leeward to get around the Lizard. He sent also sent a telegram to Falmouth for tugs to attend the vessel. As night fell the situation on the Kyber was getting desperate. All the sails were blown away making the ship impossible to manage in the heavy seas. Captain Henry Rothery let off distress signals and fired rockets when he was able to make out the outline of the Lizard light through the driving rain but it was all to no avail, around eleven o’clock that night, as the ship was pushed closer to the shore the captain let go two bow anchors to halt the drift of the Kyber, which was now, only 400 yards from the rocky cliffs of Portloe. The wind was whipping the sea’s to a frenzy with huge waves driving straight over the ship as she sank into the deep troughs, becoming submerged from stem to stern. Although the anchor ropes were bar taught they still held firm. On land the drama was hidden by the driving rain and pitch black sky, so it was not until dawn the following morning that the rocket crew from Sennen were alerted. The lifeboat could not be launched as the storm had flung great rocks all over the slipway so the rocket crew made its way up the hill towards Portloe.

At the same time as dawn broke the crew on the Kyber, who had been clinging to the rigging for over seven hours were in desperate straits half drowned and almost frozen to death. The ship was by now just a collection of bits of wood still held together by hope, but still she inched closer towards the cliffs as her anchors started to drag. As the Rocket crew ran as fast as they could towards the stricken ship, disaster finally struck. The anchor ropes were as stiff as iron bars under the immense strain and when a huge wave tore over the ship, it pounded onto her port side, turning the Kyber to leeward. The mizzen mast collapsed, then the fore and main mast, flinging the crew into the water. The stern smashed down onto the rocks breaking the vessel amidships. Within a few minutes the Kyber was a mass of debris scattered all over the beach surrounded by a sea full of floating wheat.

Only three of the crew escaped. John Harries an apprentice managed to jump overboard just before she struck, Gustavus Johannson and Leonard Willis dropped from the stern onto a patch of rocks and were rescued by fishermen and coastguards who had rushed to the scene with the Rocket brigade, who arrived to find that their job was done. The bodies of Captain Henry Rothery and 22 of the crew were later recovered and buried by the side of the tower at St. Levan church.

St. Levan Church is set in a pretty secluded valley some distance from the village of St. Levan. The church proper goes back to the 15th century but some parts are Norman. The Kybers’ grave is right by the tower, and near a great cleft stone known as the St. Levan Stone. It dates back to pre Christian times and has an interesting prophecy made by the Saint which says, that when a packhorse with panniers astride can walk through the crack, then the world is done. You can see more on this interesting Church at their website.

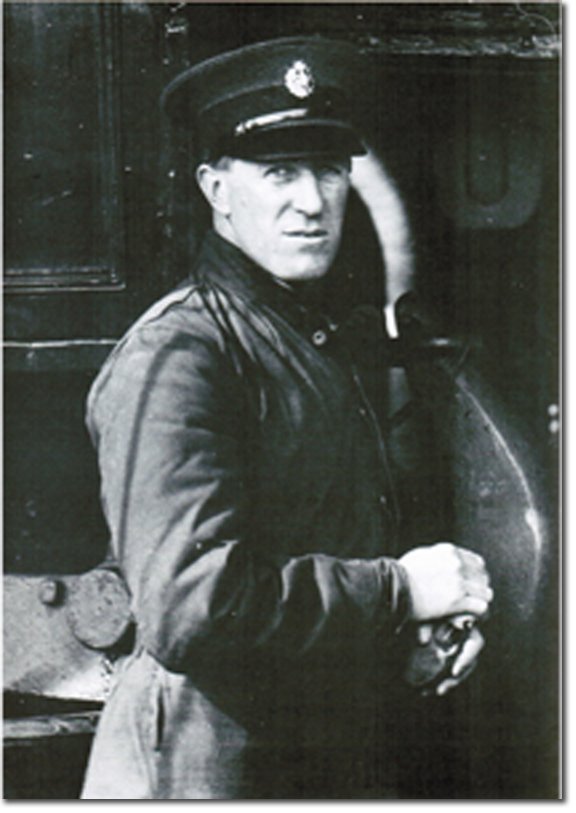

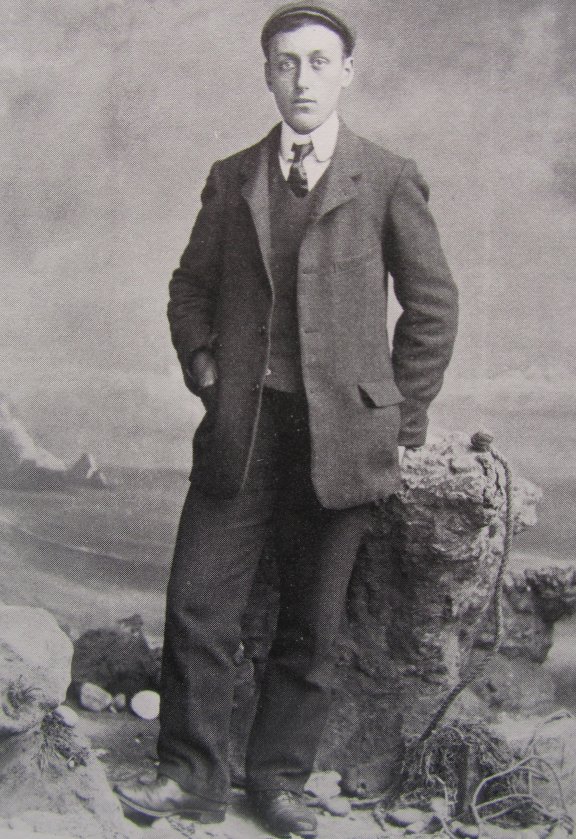

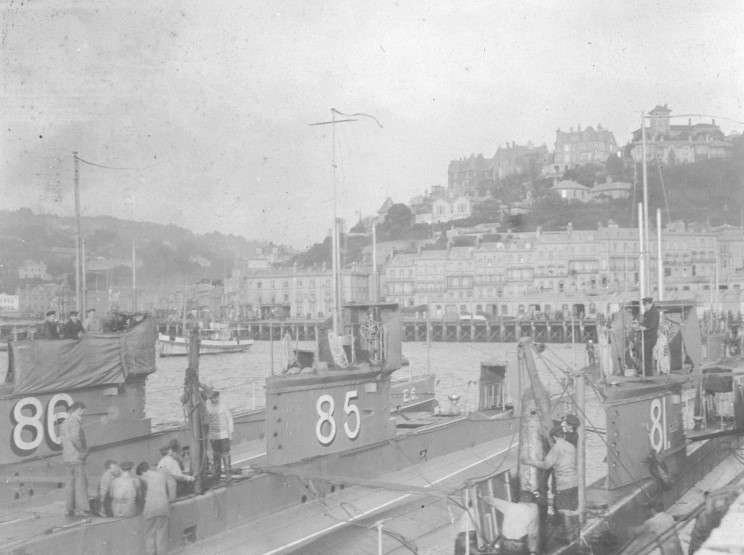

Nearby to the tower is the grave of Vice Admiral Cecil Ponsonby Talbot KBC,KBE,DSO. 1884-1970. The career of this man is incredible. It reads like a ‘Boys Own’ comic. He was in the Boxer Rebellion in China and served at Jutland. Furthermore he became one of the first submarine commanders of the Geat War, and also joined the Naval Air service in airships and blimps. Serving with distinction in the Second War he became the youngest Admiral since Nelson. The list goes on and on. I have copied a few photos from his Sons’ excellent website just to give you a flavour of those bygone days. I urge you to visit the two sites below, to learn more about this truly remarkable man

Vice Admiral Sir Cecil Ponsonby Talbot

Vice Admiral Ponsonby Talbot, photo collection

Barty Coe – The Skippers Story

I was skipper of the Asdale the night she ran ashore. I would just like give a first hand account of what took place on that fateful night. After landing our catch of mackerel to the Russian klondyker Antarctica, we found that our steering would not work and requested to the skipper that we stay tied up to his vessel till we sorted the problem, and would it be possible, because of the deteriorating weather conditions to put more ropes onto him. Due to language difficulties this did not happen but they send two of their men, one an electrician, the other a engineer aboard to assist the repair. In the meantime the trawler Boston Blenheim came out of Falmouth to try and tow us into the harbor. The wind by now had reached about force 8. After three attempts a line was passed across and our warp end was hove across to the Blenheim, but before a tow could be secured the Blenheim fell across Antarctica’s bow and sustained damage to her starboard quarter and further attempts were abandoned. By now the weather had worsened, winds reaching force 10 from the east, causing the Antarctica’s anchor to drag and both boats were being driven toward the shore,and our forward ropes parted, causing us to swing under her stern. To avoid damage the remaining mooring ropes were let go and we dropped our anchor but this did not hold. By this time we were only about quarter of a mile from shore and a mayday was sent out. It was only a matter of minutes before we were driven onto the rocks. We remained in touch with the coastguard who informed us that help was on the way from the shore. Attempts were made to launch the life rafts on the starboard side, but after getting three men into them they both broke adrift, we found out later that two men made it to the shore and the other had been thrown out of the raft. The shore rescue arrived and a breaches buoy was rigged between the cliff and the ships mast on the wheelhouse top. Just as we were about to have the first crewmember enter the buoy the ship turned over onto its port side taking with it all the rescue equipment. Out of the four of us on the wheelhouse, myself and two others managed to scramble over the side of the wheelhouse into the well of the starboard veranda. The mate had tried to come down a ladder at the back of the wheelhouse and had slipped, but was holding on. I tried to grab him by the hand but he slipped from my grasp and vanished into the sea. The two Russians who had came onboard made signs that they were going to try and swim ashore and could not be persuaded not to. They climbed over the ship and made their way to the anchor well. We found out later that one had attempted to swim ashore and had perished. The remaining crew were eventually taken off by helicopter and I was last to leave the vessel. We were taken to Culdrose naval base and because of the snow that had fallen, were unable to leave for 3 days. Sometime later the boat was checked over by the then DTI who found that the steering had been jammed by a nut that had come loose inside one of the hydraulic steering rams and there was no way it could have been detected at sea. We later heard that three men and their father, the Billcliffe’s, had attempted to help us. One can only give you all praise as well as all others that helped on the night, the helicopter crew who, because of the ferociousness of the weather were told they did not have to fly, thank God they did, Lifeboat and coastguards crews. On a final note I visited the wreck site in 2003 with the intention of looking up the Billciffe family but found that a new holiday complex had been built at Maenporth were their hotel had once been. One thing that did upset me while I was making enquiries as to what happened to the family, were the comments from the desk clerk at the new hotel. I had not told him who I was but told him I had been along looking at the remains of the wreck, to which he told me the Scottish crew had all been full of drink it being New Year. Well you can imagine how I felt, I told him who I was, and for a start we were all crew from North Shields, not Scottish, and we did not carry drink on the boat. I’m afraid I can’t tell you what I ended up calling this fellow.

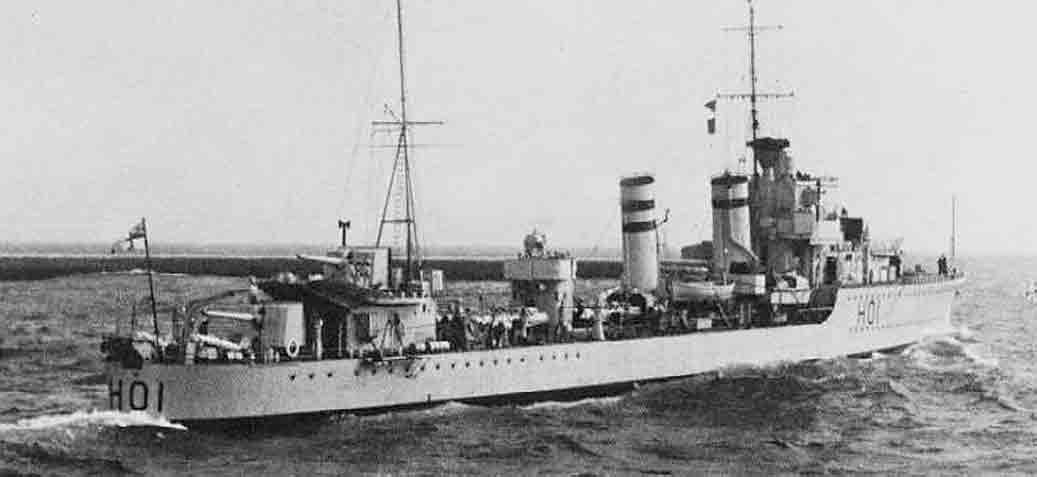

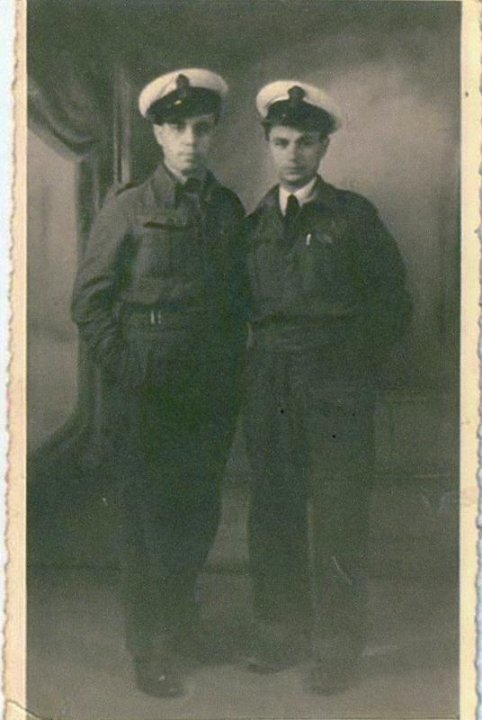

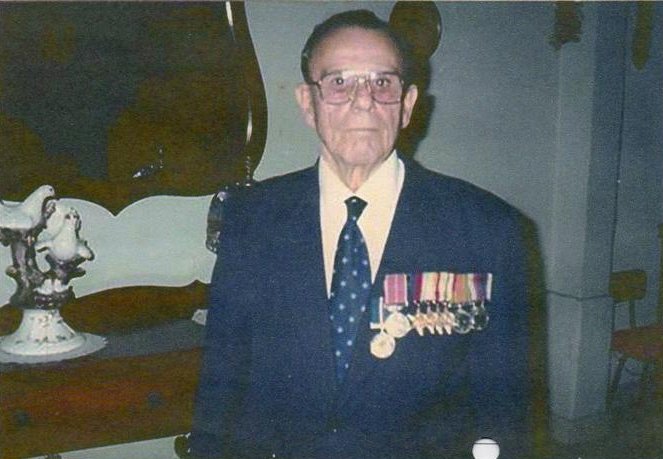

Anthony Ronayne B.E.M. survivor from H.M.S. Hardy

I joined the Royal Navy on 16th September 1939 as a Steward. My Naval number is E/LX23255 H.M.S. St. Angelo. My first ship was H.M.S. Hardy and although my main job was that of a Steward, my action station was as an ammunition supplier to one of the five 4.7 inch guns. On 30th September 1939 we sailed for Gibraltar. After a few days there, we went to the Canary Islands, then, we went to Sierra Leone, Freetown West Africa, to join Force K consisting of the Ark Royal, Renown, Neptune and six destroyers. We started patrol from Freetown straight down to South America and back for a whole month in search of the Battle Cruiser Graf Spee.

We entered Montevideo harbour for oil not very far from Rio de Janeiro. Afterwards we had a signal at 5am from H.M.S. Exeter, Ajax, Achilles (as Force K). We tried to catch up with them by doing full speed to the River Plate. We arrived too late, the German battle cruiser was already in harbour and the Exeter was so badly damaged that she had to go back to Britain. The Graff Spee was damaged too and had many killed and wounded on board. She went into the harbour with the excuse that she must bury her dead.

We waited outside the harbour for her to come out. After a few days of waiting we saw her steaming out of the Harbour, so we were all ready for her. Her Captain knew what was waiting for him outside the harbour but he had already prepared what he was about to do. He landed all the ship’s company and settled the cruiser with very big explosives explosives and lots of black smoke came up high. The Captain stayed on the ship and died there.

We then sailed for Britain and arrived in Devonport for a refit in January 1940. In February we had anti magnetic detonator systems fitted for protection against magnetic mines. We sailed from there to Scapa Flow, in Orkney where we joined forces with Force K again and started patrols. We sunk a submarine with depth charges at about twenty miles off Greenock, Scotland. We came on patrol in the Atlantic for two months and on April 9th 1940 we had an SOS from H.M.S. Gloworm. It was 11am, very heavy seas with the waves sixty feet high and it was snowing. We could only make seven knots due to the rough sea. At 2-30 pm we arrived on the spot where Gloworm was but we only found patches of oil. H.M.S. Gloworm was sunk. We tried hard to make contact with our force K as we were going to get engaged with the same two German cruisers, Gneisenau and Scharnhorst who had sunk the Gloworm.

We were only two destroyers, hardy and Havoc. At 5pm we made contact with K force, Renown and eight other destroyers. We then started a search for the German cruisers. At 3am on 10th April 1940 we found and engaged the two Cruisers. As hardy and Havoc took action we missed with two salvoes whilst the Germans tried hard to hit us. Havoc then hit the Scharnhorst aft and Renown was hit but no real damage was done. We lost them in the snow, it was too bad visibility. At 11pm we, Hardy, Hunter,Havoc ,Hostile and Hotspur entered Narvik Fjord, Norway.

We started action at 11-30pm. We sunk fourteen ships, two submarines, one destroyer and blew up a shore battery. We lost two destroyers, Hardy and Hunter. Our Captain, Warburton Lee was the first one in the war to receive the Victoria Cross. He died after leaving the ship badly wounded in his face. At Narvik Fjord we had to swim ashore. The sea was frozen with snow, the temperature was 38 degrees Fahrenheit below zero. I had shrapnel in my right leg and had to jump from the ship and swim ashore. We swam, and a good job that the place we landed had no soldiers around as their shore battery had been blow to nothing. We then had to walk to a place called Ballengen, fifteen kilometres from Narvik. We started to walk at 8-30am on 11th April 1940 and we arrived at 11-30pm the same day.

(In an interview given to a local paper ‘It-Torca published on 16 September 2001 Anthony gives more details how he managed to get safely to the shore. Before jumping into the sea he took off all his clothes except for his underwear. He then put on a life raft and jumped into the freezing water. In the meantime the Germans were firing from the shore on all those in the sea. Whilst swimming he heard an officer shouting for everyone to swim ashore, but a few seconds later this same officer vanished as he was hit in the head and drowned. As Anthony was nearing the shore he met Lt. Fawell who was almost exhausted and helped him to get on shore. Once on the shore they noticed that there was a row of barbed wire. They climbed over it and whilst walking they saw a small fisherman’s hut and went inside. There was nothing there except for a piece of curtain and Anthony wrapped it around him as he was freezing with cold. In the same hut there was a young sailor about sixteen years old who was holding one hand with the other which was ripped off his body, trying to put it back in place. On Hardy there were five Maltese crew members. Anthony together with Guzeppi Micallef and Tony Biffa walked to safety. At one stage Guzeppi Micallef could not walk further and fainted. Along came some Norwegians and put some ice in his mouth to revive him.)

Everybody was in agony with frostbite, as very few of us had shoes on. We had many wounded. The Norwegians were good to us, they put us in a school and we all lay on the wooden floor. The women came and brought hot water and bandages and they took good care of us. I was lucky as the women who bandaged my leg the next day, took me to her house and I stayed there until the Second Battle took place. She also tried to hide me so that I stayed there for good, but the officer knew I was staying in the house. The family I was with were very nice people. At midnight the officer and four sailors came for me to take me on board Ivanhoe.

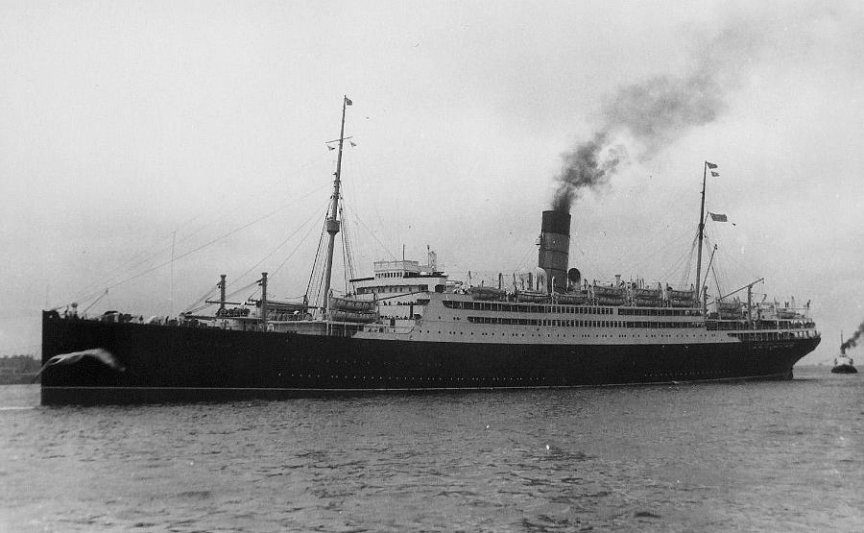

(In the same interview mentioned earlier on, Anthony stated that when he boarded the Ivanhoe he met the other Maltese and they were delighted to see one another once again, and all of them expressed their joy at being so lucky to still be alive. On Ivanhoe it was decided that there was insufficient room for all the survivors so some including Anthony were taken on board H.M.S. Kimberly. Unfortunately she was then ordered back to Narvik to pick up other servicemen and then all of them were transferred to the troop ship Franconia which got back nearly two weeks afterwards . Meanwhile the Ivanhoe had sailed straight back to Scotland and so Anthony learned via the BBC World Service, all about the homecoming of their shipmates and the way they were feted and welcomed back by Winston Churchill)

On the way back in the troop ship Frankonia we had many air attacks until we came back to Greenock in Scotland. We arrived at 7am. As soon as we landed we were taken to the Guildhall for dinner. Admiral Andy gave us a speech, how nice it was to be back in the UK. The first chance I had, I ran to the telegraph office and send a telegram home ‘Tony is safe. I had no money for it but everyone in the office wanted to pay. I was dressed in rags and they thought that I was a student, as on that day the students made a Carnival Day. (In the interview to the local newspaper, Anthony reveals that before this telegram was delivered, his family and friends paid for Masses and special prayers to be said in repose of his soul, as was the normal custom in the Roman Catholic Church here in Malta, because all of them were certain that Anthony was dead) We left Greenock next day for Plymouth. We arrived at Drakes barracks, Devonport at 2-30pm. We had been medically tested and given new uniforms and a complete kit. We stayed in the barracks for a few weeks.

Anthony spent twenty five years in the Royal Navy, joining in 1939 at the outbreak of the war and left in 1967. The latter part of his service was as a training instructor at St.Angelo. He was awarded the British Empire Medal (BEM) for gallantry during the war, when his actions in Bari, Italy, saved lives.

Roy Phillpot’s memories

Here is an account of what it was like to be on board the Glen Strathallan as a cadet, sent in by Roy Phillpot.

I was quite sad to hear the old girl was semi broken up on the bottom, but I suppose it would be a sad affair if she caused a fishing boat to sink – even though they should know where they go with modern nav systems as they are. I am not sure what more I can tell you. You seem to have done your research well, and unfortunately as a poor radio officer student, I did not have much of a camera, and did not risk it on that first trip. The few pictures I did have are gone with the various moves and family upheavals.

I remember the ship sitting at Millwall dock in London, with a black painted hull – the paint being many layers thick, and applied generously over various chipped areas where the rust had been removed. Riveted hull, so that when standing on the dockside at the bow, you could see the lines of rivets curving away towards the stern. A wide well formed hull, obviously designed for strength and good sea handling. The accommodation was white – with some rust streaks, and a big yellow painted funnel – at least that is my memory, with two high I think also black painted masts and the radio antenna between them. The accommodation doors heavy, watertight, and with dark narrow stairs leading up and down into the various accommodation areas. She had been converted for carrying cadets. Our bunk area was in the two fore holds – what used to be fish holds. 2 tier bunks, with the top bunk not far from the deckhead. There was not much headroom up there!

Light was from a few deckhead light fixtures, but I remember the light was dim and yellow – each held a 40 watt bulb, it could not have been more, and was probably less. The single switch was at the entrance to the hold. Our instructor would come and turn it off around 8 or 9pm, just before the engineer turned off the steam driven donkey generator. It then became extremely dark and very silent – apart from the remarks and various pranks from our assembled company! Smoking was forbidden, so anyone wishing a smoke had to go outside. Without a torch, this was an adventure in itself! The main cabin, which was also the chart room, below the bridge, had warm dark panelling, with a number of rather dirty windows, which could be covered with heavy red curtains. These were closed when we did navigation exercises using the Decca navigator.

From the main cabin, a narrow half winding stair led up to the narrow bridge above. Here was the wheel, engine telegraph, radar, and speaking tube to the engine room and chart room below. Maybe there was also a phone to the engine room, but I can no longer remember. I was always fascinated by how well the old speaking tube technology worked. We even had it in more modern ships I sailed in later! Simple and foolproof. We used it on the Glen Strathallan to give navigation commands to the bridge when we were “playing” navigation below.. Blow, listen, and speak. Navigation was done on the chart table at the fore end of the cabin, and at the aft end, was a longer table for school work, with bench seats. The simple old radio equipment was on the Port side bulk head and small table, with a large rotary transformer in a cupboard below. Gleaming copper tubing led up to a ceramic antenna feed through insulator on the Port side bulkhead, going out to the antenna above.

I can remember nothing much more about the accommodation, I believe our instructor had his own small cabin, but I never saw it. The captain , engineer , and bosun obviously had theirs, but again I know nothing about them. The showers and toilets were somewhat primitive dark and small. I am pretty sure the toilets went straight over the side. Pressing the flush mostly brought a rusty trickle, sometimes however a loud burp and a spray of water and air. It was a bit risky using them! The engine room was something I will never forget. It was really a large space for such a small ship. Lit sparsely via the skylights, and a few yellowish glowing bulbs in safety fittings.

The centre piece being the really huge compound triple expansion steam engine. To get into the enginroom, I think from the starboard side, was a steep narrow stairwell, this led to a platform above the steam driven donkey generator on an intermediate platform. Maybe we had a second main generator, but I only remember this one, with a large flywheel covered by a flimsy wire mesh guard, driven by a couple of pistons. The whole thing leaking steam from various joints and valves. It was surprisingly quiet, but then it probably only had a power of a few kilowatts. I remember our power supply was 220v DC. Down some more ladders to the engine room main plates. Foreward to the huge boiler and the engine controls. Various pumps, mostly steam driven, a few electric as humps sticking up from the plates. She had been converted to oil burning, so the oil burners flickered, and when running, the enginroom fans roaring and the thickly insulated steam pipes vibrating, made it seem like something from Dante’s Inferno.

We all had to do some watches down there, but it was not something I enjoyed. Wiping down the main engine in the evenings after we stopped was far better. At least then there was no high pressure steam in the pipes. I was always a bit nervous about that. On deck, we were set to chipping and painting. The paint locker in the forepeak, cramped, dim, and full of tins, tools, and smelling heavily of tar and solvents. we were only allowed in there with the Bosun, who dolled out the things we needed for our allocated jobs. He collected and checked them again when we had finished. We always had to clear up after what we had done, and the deck must be swept or hosed down. Considering her age, the ship was in good condition. The Bosun made sure she was kept that way. The deck I seem to recall was quite cramped too. Not a lot of space, and somewhat rusty. I am only 59, but all this was aroundbut all this was around 40 years ago, and the memory dims with time. I tend to mix the Glenstrathallan up with some of the other earlier ships I was on, so I cannot guarantee that the above impressions are totally accurate.

Harry Rogers, survivor from H.M.S.Hardy

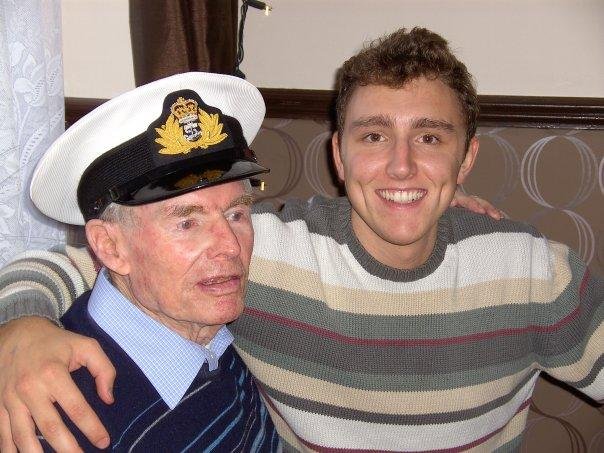

Aged 92, (2010) Harry Rogers is probably the last remaining survivor from the Hardy. I am very gratefull to his son Tony, grandson Alex, and of course Harry himself for sending me the story and photo’s below. HARRY ROGERS Harry was born on 28 November 1917 in Baxter Street, Middlesbrough, an area which you will now know as Middlesbrough Bus Station. As you can imagine times were hard back then and malnourishment was common. Harry, like most men of the day, ended up working at British Steel from the age of 16. He left British Steel to join the Navy in 1936.The harsh, laborious conditions at the time killed most men before their 60th birthday, so my Grandfather professes that joining the Navy saved his life. Harry joined Devonport Barracks in Plymouth for his basic training as a ‘Stoker’ – Engine Room hand, and on completion of training was selected for a destroyer in the 9th Mediterranean Flotilla – HMS Hardy.

At ‘Action stations’ everyman on the ship had a job, but not necessarily in their core role. In my Grandfather’s case his job was ‘ammunition supply’ to Number 4 turret at the rear of the ship. When Hardy ran aground it was because she’d received battle damage to her engines and steering positions. The helmsman had been killed, and the weight of his dead body slumped over the wheel was forcing the ship to port (the left). At some stage during the battle, my grandfather found himself on the upper deck of Hardy with two other Stokers who were both Chief Petty officers. The Captain at this point had been mortally wounded and Harry, with some others tried to lower the body down from the bridge on to the next deck using a stretcher. They then proceeded to lower the ‘Captain’s Launch’ a small boat on a winch system. To do this the three stokers stood shoulder to should to grasp the long brass handle and wind the boat down. Whilst they were doing this a shell from a German destroyer hit the ship somewhere close to them. Shrapnel from this shell killed the two Chief Stokers outright, tearing into the gullet of one and severing the arm of another. My grandfather felt something ‘bite’ him but continued to try and get the Captain’s body ashore. Within seconds he was in the icy cold water of the fjord. The Captain’s body was dragged ashore but he was considered dead. It was too cold and dangerous to carry him. They agreed to go back for him.

The shore was not far away and Harry was a strong swimmer. He remembers walking up the beach and noticing blood in the snow. Then he realised that the blood was coming from him. He doesn’t remember much after that. He says that he was picked up by locals, as the next thing he remembers clearly, is waking up in what looked to be a school hall being attended to by a local girl. The only way out of occupied Norway by land, was over the mountains into neutral Sweden, but the locals would not take the wounded as they would never have made it. What they did do was fix them with clothes and feed them with whatever little they had. Three days later the Royal Navy battle cruiser HMS Warspite led nine destroyers up the same fjord and defeated whatever German Naval assets were still in the area. The survivors from the Hardy watched with dismay as the British ships departed, not realising that the men in Norwegian clothing waving at them from the shore, were British sailors. Two of the surviving officers from HMS Hardy used a motor boat from a previously captured British iron ore ship to get a message to one of the departing ships. The admiral dispatched two destroyers to return and collect the survivors. Harry was collected by HMS Ivanhoe on 13th April 1940 and returned safely to England. The survivors were taken to Horse Guards where they met Winston Churchill. Harry never made it as he was still recovering from the ‘bite’.

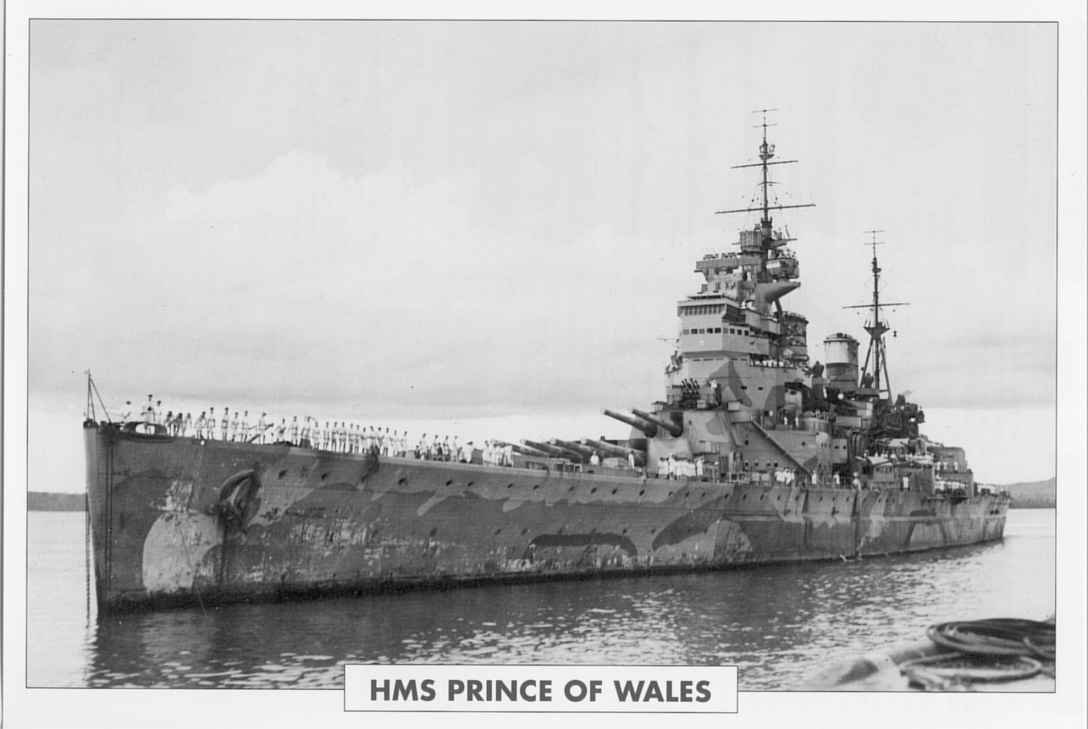

That bite turned out to be a piece of shrapnel about the size of a 50p piece which lodged itself very close to his lungs and heart. The icy water of the Norwegian fjords prevented him from losing too much blood. The shrapnel was too close to his heart to operate the doctors said, yet he made an almost full recovery although he still cannot lift his right arm fully to this day. All this wasn’t enough to stop Harry from leaving the service. On the contrary, Harry’s next ship was the King George the V class Battle Cruiser, H.M.S. Prince of Wales. Harry saw action on this ship against the German pocket battleship Bismark, and was still onboard the Prince of Wales when her sister ship H.M.S. HOOD was sunk by the Bismark with the loss of all but 3 lives – a very famous sinking indeed. In December 1942, in the South China Seas, Harry was still onboard H.M.S. Prince of Wales when it was dispatched as part of force ‘Z’ to the South Pacific. She was sunk by Japanese bombers on 10th December that year. That is another amazing story of survival, in which my favourite quote from my grandfather is that, ‘ he never left the ship – the ship left him’ as he was sat on the keel when it went under.

Escaping the island of Singapore before it’s capture by the Japanese, he found himself employed in a variety of vessels until he was posted to the USA to become part of the 20 strong crew of one of the hundreds of Landing Craft (Infantry) built for the Allied landings in Europe. Harry saw action at Anzio – landing the Black Watch Regiment with the 8th Army in the historic capture of the Italian Peninsula (Seen the film?)

Harry left the Royal Navy as a Chief Petty Officer after 14 years service. Worked as a foreman at ICI until 1979 when he retired from work.

He now lives in Redcar with his wife Eileen, (Who, as many will agree is the reason he’s lived so long). They have 5 children, the second eldest of which also became a Chief Petty Officer in the Navy choosing submarines over surface vessels. Harry’s eldest Grandson, Alex, who studied at St. Mary’s College in Middlesbrough is the 3rd generation to join the Royal Navy only this time as a commissioned Officer. Lieutenant Kopsahilis, joined the Navy 6 years ago afer completing A-levels and is now a fighter controller onboard one of the Royal Navy’s newest warships Her Majesty’s Ship DARING. She’s the first of a brand new class of six anti-air warfare destroyers being built in Scotstoun, Glasgow.

In November 2006 Alex was lucky enough to be drafted to HMS Ocean – A Helicopter Landing Platform travelling to Norway to take part in an annual exercise with Royal and Norwegian marines. Whilst there, he stepped ashore and visited the the Museum at Narvik where he found lots of articles from the ship including a photo of the survivors in which his grandfather was present. He also mentioned the story to the ship’s Chaplain who arranged for a service of Remembrance to be carried out at the cemetery where the sailors of that battle were buried in the nearby village of Ballangen. It was quite moving to be able to lay a wreath on the Grave of his grandfather’s old Captain, Bernard Warburton-Lee with a personal message from Harry.

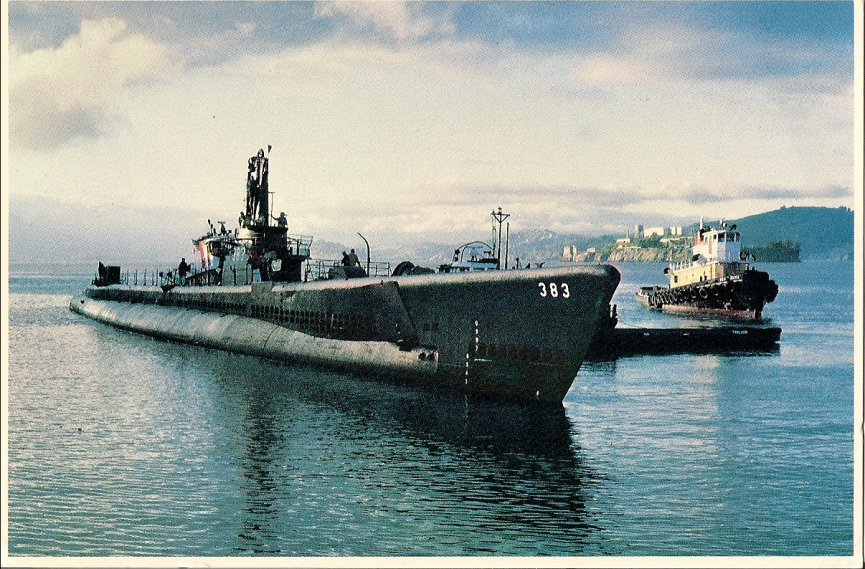

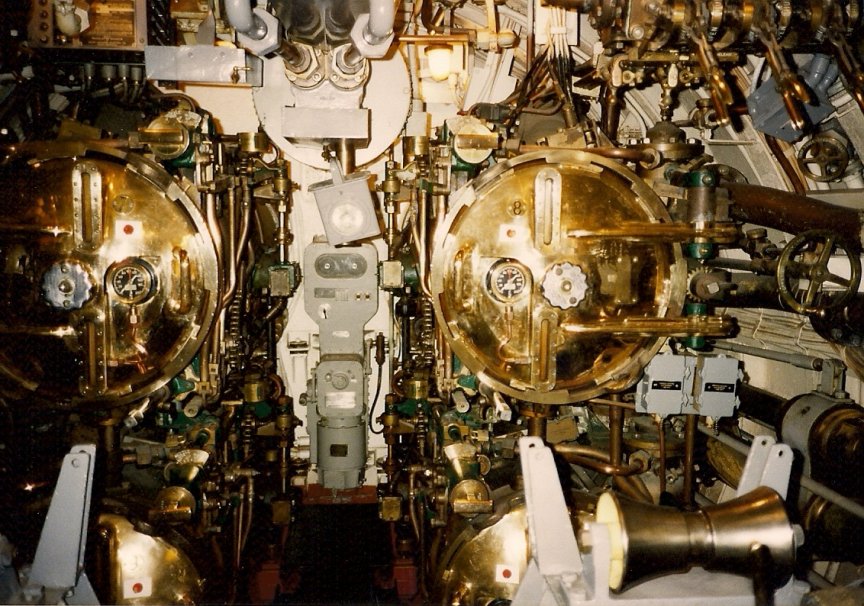

Submarine U.S.S.Pampanito

American World War Two submarines don’t have the same glamour or menace as their more famous U boat counterparts, but none the less they performed sterling service and were responsible for sinking nearly a third of the Japanese Fleet. In the process they suffered a twenty three percent casualty rate, which whilst not anywhere near the U boats eighty percent rate, is still a huge loss and amply demonstrates the Americans bravery and skill. You would think that they would point that out a bit more, but on the Pampanito’s information sheet they seem more interested in telling you about the Disney designed logo, the ice cream machine, and the fact that the boat was used in the film Down Periscope. All very interesting stuff, but it’s not what this submarine is about. It’s a weapon, and judging by its record, a pretty effective one.

The USS Pampanito (SS-383) was built in the Portsmouth Navy Shipyard, New Hampshire, in March 1943 and was commissioned into the fleet in November of the same year. She is a Balao class (some sort of small fish) diesel electric submarine, 311 feet 6 inches long with a beam of 27 feet 3 inches. She was powered by four Fairbanks Morse diesel engines, and four high speed Elliot Electrical motors with reduction gear. On the surface the Pampanito could run at just over twenty knots, and submerged she could manage nearly nine knots. Overall the submarine had a range of eleven thousand miles on the surface and could dive to an operational depth of four hundred feet, although on one occasion she had to dive to over six hundred feet to avoid Japanese depth charges.

For armament the submarine had ten torpedo tubes, six forward and four aft, and carried twenty four torpedoes in all. On deck she carried four machine guns and a four inch deck gun. To operate all this, the Pampanito carried a crew of seventy men and ten officers.

During her combat career the Pampanito sank six enemy ships, damaged four and probably just as importantly saved the lives of 73 British and Australian P.O.W’s who had been left floating in the sea when their ship was torpedoed. You can read all the War Reports including the rescue by following this link.

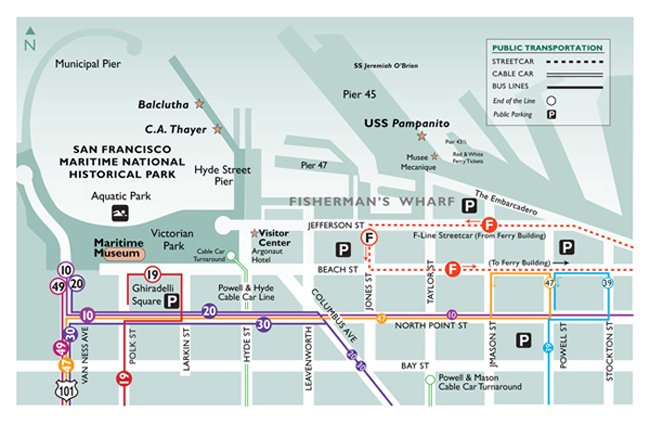

So what of the Pampanito today? Permanently berthed at Pier 45 near Fishermans Wharf in San Francisco the U.S.S. Pampanito has become a very popular museum.

I saw it in the 1990’s, and I have to say it’s a remarkable job of restoration and preservation. The Americans don’t stint on this sort of thing. The boat is regularly maintained and dry docked, and the restorers scour the country for missing bits of equipment and spare parts. Inside everything has been polished and painted to within an inch of its life, and the tour is interspersed with voiced memories of the actual wartime crew. It is all very evocative.

When I saw the boat, the commentary on the audio guide was by the celebrated writer, Edward.L.Beech who wrote a classic submarine book, Run Silent- Run Deep, and his knowledge certainly imparted a sense of what it must have been like to serve in one of these steel tubes, fighting their battles in the half dark of the vast ocean. Whilst not as mesmerising as some of the preserved U boats, the U.S.S.Pampanito is well worth a visit, and its presence serves as a lasting memorial to all those Submariners, who perished in that terrible war.

Emma Christ

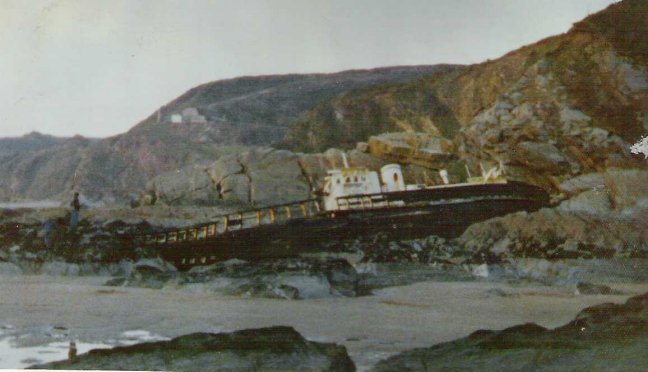

This is one of the first shipwrecks that I saw on the Cornish coast. It is on the beach over towards Polhawn Cove on the Rame Head side of the Bay. There is a convenient car park, and the path down to the beach is easy to find and not too steep. It is a lovely part of the Bay, much loved by families and their children as the sea is usually sheltered by Rame Peninsula and so safe to bathe in. In 1975, Mr. Burland put most of his savings into a boat called the Emma Christ which he bought from the Ministry of Defence. The idea was to convert it into a diving tender. During the rest of the year the work proceeded at a good pace and by November 1976 she was ready to take her Board of Trade Survey, which was held in Dartmouth. N Saturday November 8th the Emma Christ set sail from Plymouth to conduct trials in Whitesand Bay. After an hour or so the engine stopped due to a fuel blockage, and the ship rode at anchor for three hours whilst the crew tried to sort the problem out.>

Suddenly there was a loud bang as the anchor cable parted and the ship started heading for the shore. Although there wasn’t a full blown gale the seas had got up and as the ship neared the rocks the surf became much more severe. The crew couldn’t start the engine, because the air bottles needed to turn it over were empty, and the air compressor seized up after only working for a few minutes.

In desperation two more anchors were thrown over but they didn’t hold and within minutes the Emma Christ was swept onto the rocks. Mr. Burland sent up flares and the Lifeboat and Helicopter were scrambled. When the helicopter arrived the ship had been pushed under the two hundred and fifty foot cliffs, was beam on, and being buffeted quite strongly by the waves. Two crewmen had scrambled off the ship on to the rocks, but the Lifeboat could not approach near enough to rescue the other two crew, so the helicopter, hovering very close to the cliffs winched the other two off the boat to safety.

The next day Mr. Burland stood on the cliffs looking down on his ruined boat. The Emma Christ was already starting to come apart and he new that salvage was not an option. His hopes of running a diving tender were over, and all that was left was the dream.

Now a days there is not a lot left of the Emma Christ except for a rusting boiler half buried in the sand and masses of iron plate sticking up out of the sand. Still the walk is great, even if the climb back up is a it of an effort.

Who We Are

As you’ve probably guessed, Submerged Productions is run for fun rather than profit. Submerged Productions is essentially a cottage industry, run by myself along with a lot of support and encouragement from my wife Joyce and the invaluable help of my dive partners – Sound Diving’s Steve Carpenter, Dave "My Flower" Page, Brasso Brassington, now sadly removed to the wilds of Nottingham, Pete Hearn who also keeps the boat running,and Geof Skinner who keeps the whole show on the road with endless cups of tea and practical help. A later addition was the incomparable Sally Tyler who is a marine biologist and worked for the D.D.R.C. Luckily for her she escaped our clutches and ran off to marry a nice policeman and have a family. The latest person to join the crew is Peter Rowlands, a superb underwater photographer and contributor to many publications.

I also received a wealth of research tips and treasures from Steve Johnson, John Benhenha, Dick Larn, George Sandford and Al Down,and most importantly Gordon Crimp who was invaluable in the early days.

Without the help of Roger Webber I would have never found the A7 in the days before sats or some of the other wrecks in this site. I am also very grateful for other dive skippers like Richard King and Dick Linford who freely share their information on different dive sites.

While I’d naturally be delighted if you bought any of my books and videos, all I really hope is that you enjoy the information on this site and that it contributes in some small way to your enjoyment of diving.

Forthcoming

The Fatal shore

Most of the shipwrecks along the Westcountry coast have come to grief by hitting the shore. Hundreds of ships wrecked, and thousands of poor souls drowned. This video tells their stories, and visits some of the wrecks underwater.

The Eddystone Reef

This is a working title as I am still not sure what to call this film. Its about the Eddystone reef and how it was formed, what lives there, and all the wrecks that have come too grief on its famous rocks. I also want to weave in the story of the Eddystone lighthouses as well, so its a big project.

Scylla

I am in no hurry about this one as I want to see the effects of a bad storm on this wreck. However we have started filming so we can get all the changes, especially as the fish arrive.

I followed this ship around when I was in the ‘Mob’ so I am quite interested in her history. I actually dida couple of diving jobs on her, so its a bit wierd to see her now.

This project is not iminent as I want to see the effects of a bad winter on the wreck. But I followed this ship around when I was in the ‘Mob@

Test3

test3

Test Post

How is the formatting for bold

Is the plain text nice and clean as it should be. What does a link look like

Hello world!

How does the bold text look

and the normal text. How are links