High above the stormy sea on Marwick Head, five miles east of Dounby in Orkney, stands a lonely crenallated tower built by public subscription to honour the memory of Lord Kitchener who was lost in June 1916, when the cruiser H.M.S. Hampshire sank nearby. Off the 667 officers and men on board, only 12 survived.

The official version of events stated that the Hampshire was taking Lord Kitchener to Russia to persuade the Tzar to keep his country in the war, when it struck a mine laid by the German submarine U75. Because Kitchener’s body was never found, rumours about his death and his mission to Russia abounded, reaching the same fever pitch as the ‘Who shot J.F.K.’ conspiracy. For instance, why were troops sent to stop locals rescuing the few survivors that were washed up on the shore? Had Kitchener been on board at all? And where was the gold bullion, supposedly being taken to Russia to bribe the Tzar if all else failed? Had the I.R.A. assassinated him? Kitchener had incurred their wrath by giving his approval to the bloody suppression of the Easter uprising of 1916, and the protracted series of executions that lasted through out May of that year.

However the most persistent rumour was that a Fritz Joubert Duquesne, a Boer who hated the English for they had done to his Country, had disguised himself as the Russian Duke Boris Zakrevsky, and joined Kitchener in Scotland. He was suppossed to have signalled the German submarine, and got off H.M.S. Hampshire by using a life raft before it sank. He was apparently awarded the Iron Cross for his efforts. Interestingly the same Dunquesne ran a huge spy ring in the United States of America in the Second World War until he was caught by the F.B.I. in what became the biggest round up of spies in U.S. history. What is fact and what is fiction I will leave you to decide, and point you to this great site www.hmshampshire.co.uk that has lots more info and photos.

So who was Lord Kitchener, and why all the fuss? It is difficult to point to anyone in public life today and say that they are a National Hero, but that’s exactly what Kitchener was. Born in 1850 in Ireland, he came to prominence as an Aide de Camp in the failed mission to rescue General Gordon in the Sudan. He then achieved national recognition in his second tour in the Sudan (1886-1899) by defeating the army’s of Abdullah al-Taashi, the successor to the Mahdi, at the battle of Omdurman. The Mahdi had defeated and killed General Gordon, one of the great heroic figures of Victorian England, so after the battle, to avenge Gordon, Kitchener had the Mahdi’s remains exhumed, burned, and scattered in the river. For his efforts Queen Victoria appointed him Knight Commander of the Bath and made him Baron Kitchener of Khartoum.

In December of 1899 Kitchener, now a Major General, was in South Africa for the start of the Second Boer War. In a brutal and savage conflict, Kitchener humbled the Boers by laying waste to their farms and driving their women and children into specific areas where they could be controlled. These areas became known as Concentration Camps. Conditions were dreadful, and in the end twenty six thousand women and children died of starvation. Kitchener had won, and they made him up to a full General, but his legacy of Concentration Camps, would later come back and haunt the world.

At the outbreak of the First World War, it was Field Marshall Lord Kitcheners face, on probably the most iconic poster in the world, saying Your Country Needs You, that incited thousands of eager young men to join up and fight the Germans. By now Kitchener was Secretary of State for War. Only with him at the helm, so the Country thought, could the Great War be won. So what about H.M.S.Hampshire and the secret mission to Russia?

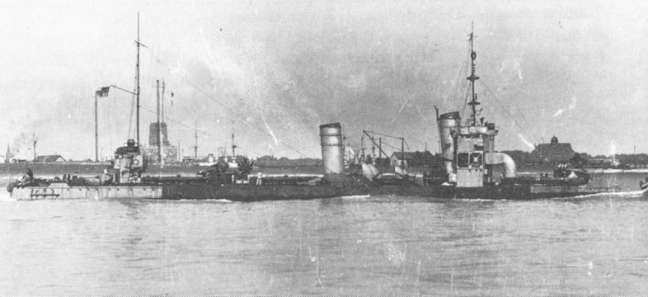

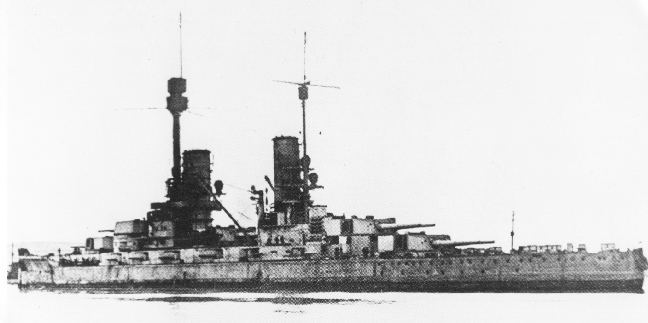

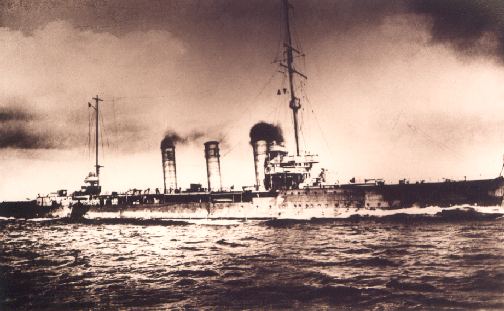

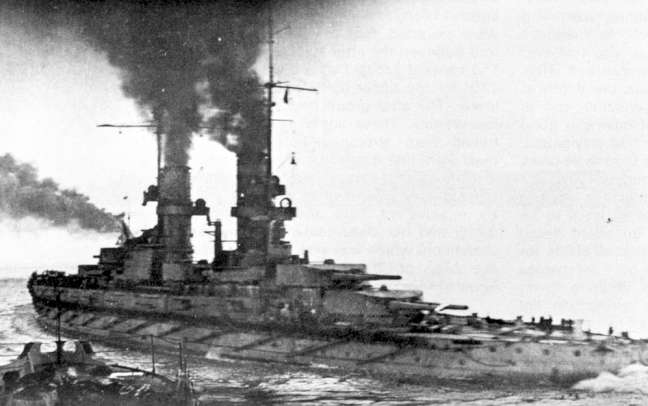

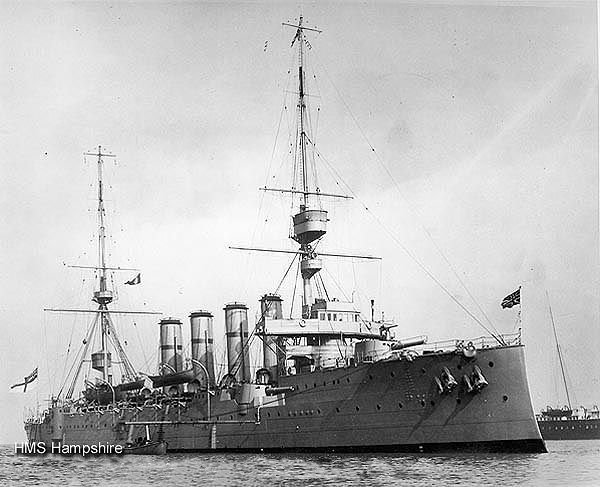

The armoured cruiser H.M.S.Hampshire was launched on the 24 September 1903 and was built by the firm of Armstrongs at Elswick. When she was completed in 1905 she joined the Channel Fleet and served in the Mediterranean and the China Station, returning to Scapa Flow, where on the 30 may 1916 she sailed as part of the Grand Fleet to fight at the Battle of Jutland. She returned safely on the 3 June to Scapa Flow, but was immediately ordered to embark Lord Kitchener and his staff, and proceed with all haste to the port of Archangel in North Russia. Here Lord Kitchener was to have urgent talks with the Tzar.

The weather was appalling with gale force winds and mountainous seas, but the mission was deemed so important to Britain’s war effort that the Hamshire, under the command of Captain Savill, had to sail immediately. It was a bad decision and the ship did not get far. An hour after setting sail, Captain Savill decided to call it a day and return to the safety of Scapa Flow. However at twenty to eight in the evening, the Hampshire was racked by a huge explosion that ripped out the middle of the ship. She was about one and a half miles from the shore between the Brough of Birsay and Marwick Head, when she rolled over and quickly sank, taking most of her crew of 667 to the bottom.

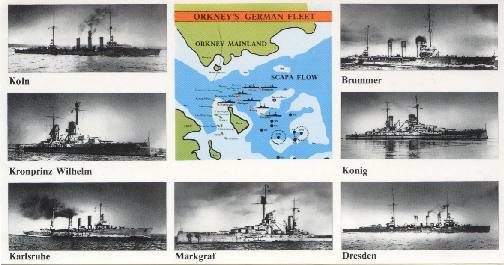

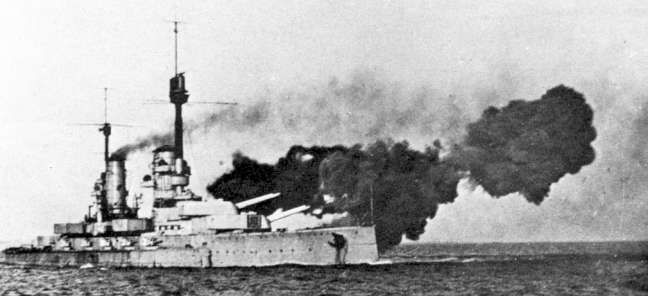

At the time it was thought that she had run into a string of twenty two mines laid by the German submarine U 75 commanded by Kapitanleutnant Curt Beitzen, who had been dispatched to watch the Grand Fleet as they left Scapa for the Battle of Jutland.

As the news reached Scapa Flow rescue ships were dispatched, but by the time they reached the area the Hampshire was gone, and only fourteen men in a Carly float reached the shore, two of them dying before they could be rescued. Over six hundred men were loss that terrible day. Many more would have been saved, but the life boats were smashed to pieces by the horrendous waves as they were lowered into the sea.

So what of Kitchener? Well many of the men who survived stated that Lord Kitchener was not killed by the explosion and must have made it to the upper deck, as they told to ‘make way for Lord Kitchener’. None of them saw him after that, and his body was never recovered.

The money for the Kitchener Memorial was raised by the people of Orkney, and was dedicated in 1926. The inscription on the plaque says it all. This tower was raised by the people of Orkney in memory of Field Marshall Earl Kitchener of Khartoum on that corner of his country which he had served so faithfully nearest to the place where he died on duty. He and his staff perished along with the officers and nearly all the men of HMS Hampshire on 5th June, 1916. I am grateful to Brian Sandom for the following information and photos.

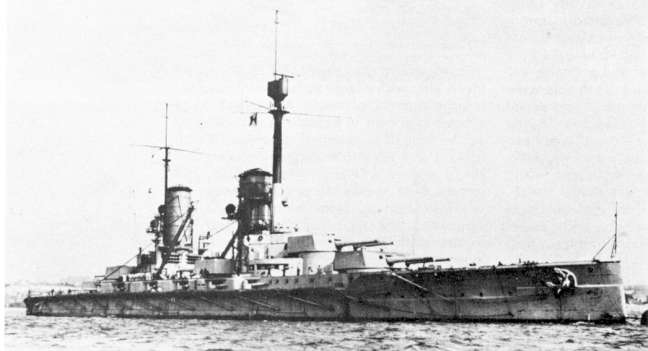

Some crew of the Hampshire, Gibert James Sandom is the very tall man in white wearing a Royal Marines hat.