I first saw the Cutty Sark in 1980. It was in the same dry dock as it is now, but Greenwich then was a very different place to what it is now. Then it was very rundown, but now with the coming of the O2 and lots of regeneration money the place has been transformed. Now, ‘Maritime Greenwich’ is a World Heritage site where you can see all manner of things including the Royal Observatory.

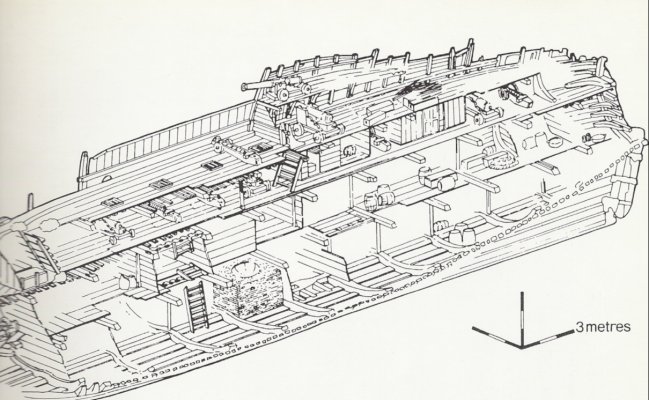

The Cutty Sark had been open as a tourist attraction by the Queen in 1957 and until the fire that nearly destroyed her in 2007 more than 13 million visitors had walked her decks and peered into her vast holds. A year before the fire started, the Cutty Sark had been closed to the public for much needed repairs and conservation work. One of the biggest challenges faced by the conservers was the need to introduce a new support system for the ships’ hull. When the Cutty Sark had been dry docked all those years ago, she was done in the conventional manner, with her keel resting on blocks at the bottom of the dock with large baulks of timber props holding her upright. Over the years this put an immense strain on her hull and was starting to distort it quite badly. The other big problem besides the constant leaks in the deck, was the preservation of the vessels composite construction. The Cutty Sark is not a wooden vessel but a ship made up of many thin wrought iron frames on to which are bolted wooden planks. This had the advantage of making an extremely strong hull with much more room in the holds because it did not need the massive beams a wooden hull needed.

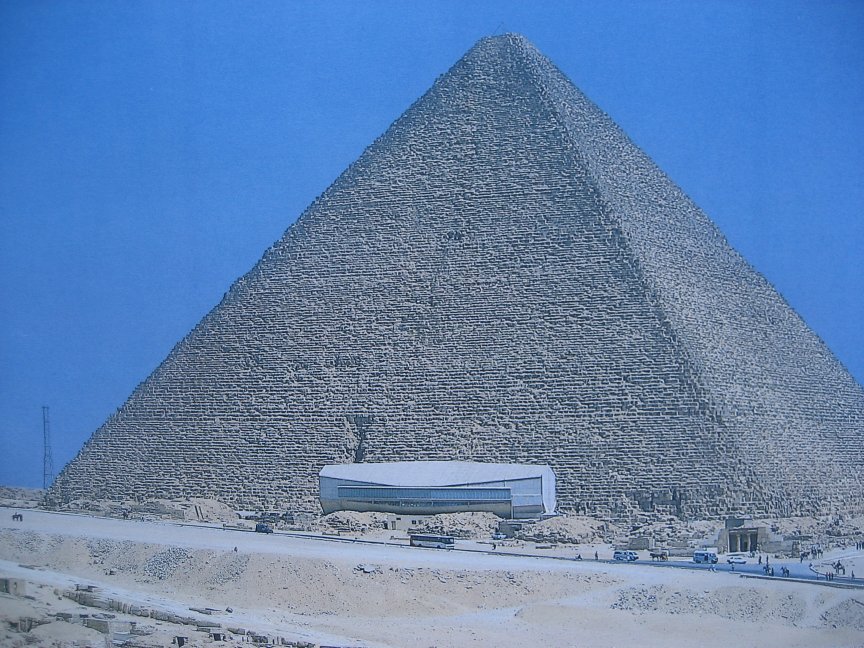

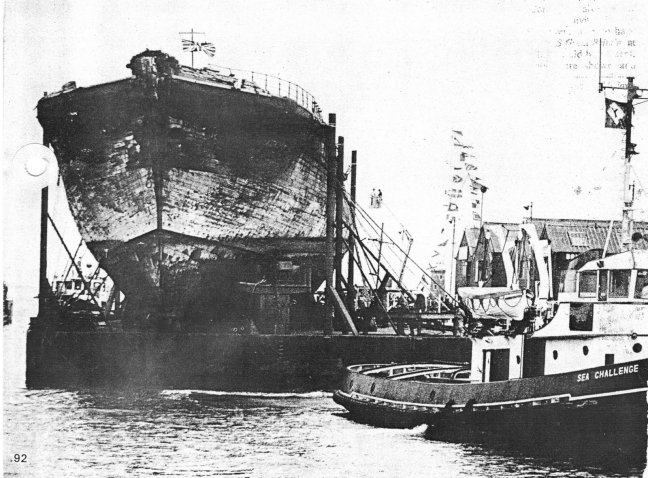

To get around the distortion of the hull, the conservers came up with the elegant idea of raising the hull three metres in the air and supporting it with steel props. It is a fascinating piece of engineering which allows the visitor to walk right under the hull. At just above dock level the gaps have been glassed in, so that the ship looks as if it is floating. It is a very clever and practical idea.

Nowadays we have all heard of the ‘War on Drugs’ but in the 18th Century England was engaged in the Opium trade in a very big way and the British Government, through the East India Company, trafficked huge amounts of opium into China. The Chinese had banned opium in 1799 but like today they found that it was impossible to halt the illegal trade so they seized and destroyed shipments in Canton. The British were outraged, seeing the Chinese actions as a restriction on free trade and declared war in 1839. The Chinese were no match for the Royal Navy and in the end were forced to cede Britain a number of ports including Hong Kong. So what was all this about? Well tea, the humble cuppa. Tea was fashionable, expensive and produced exclusively in China until the mid 19th century. Tea had been introduced into England by the wife of Charles 11, Catherine of Braganzer and

despite being heavily taxed was enjoyed by all social classes, mainly due to the fact that it was smuggled in vast quantities into Britain, so much so that at one time, more illegal tea was smuggled into the country through the Netherlands than through the legal importers of the East India Company. The reason for the opium trafficking was the fact that the East India Company had to pay for the tea in silver, as the West had little in the way of trade goods that China wanted. To redress this so called trade imbalance, the East India Company grew opium in India and sold it to smugglers to run into China. The smugglers naturally had to pay for the opium in silver.

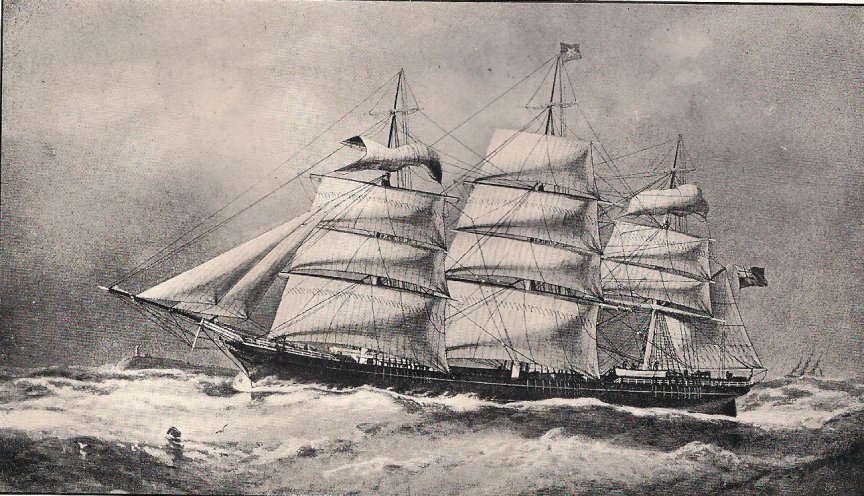

Determined to support the Company the British Government slashed the tax on tea from one hundred and twelve percent to twelve and a half percent. As tea became cheaper sales boomed and were further increased by the Temperance Movement, who in the 1840’s, promoted tea as an alternative to alcohol. A second Opium War broke out between 1856 and 1860 which resulted in more ports being opened up to Europeans including the important tea port of Hankow which was hundreds of miles up the Yangtze River. All this did not profit the East India Company much as the British Government was later forced by the Free Trade Movement to end the Company’s monopoly with China. This left the tea trade wide open and with demand for tea sky rocketing ever upwards there were fortunes to be made. Clipper ships like the Cutty Sark were built with the express purpose of shipping tea from China to London in the fastest possible time. Speed was vital and as the first home got the highest prices the ships became increasingly competitive and so the great tea races began. To give you an idea of how competitive these skippers were, there was a race in 1866 where five ships starting within hours of each other sailed 15000 miles from China to England over a period of ninety nine days, and when the first ship, called Ariel, arrived off the Kent coast,, she was only ten minutes ahead of her rival the Taeping.

It was into this fiercely competitive trade that the Cutty Sark was launched in November 1846.She was owned by John Willis, who at nineteen, had brought home his first tea cargo and now owned a fleet of clipper ships. The Cutty Sark was 64.74 metres in length with a beam of 10.97 metres and a displacement of 2100 tons. She was able to carry 1700 tons of cargo and her 32000 square feet of canvas was tended by a crew of between 28 and 35. At the time that Willis placed the order for the ship, American clippers were the fastest ships and although the British ships were some of the finest in the world they had yet to win a single tea race. In 1868 the Aberdeen clipper Thermopylae had set a new record of 61 days for a voyage between London and Melbourne in Australia, and Willis was determined that his new ship would do better. Not only was there a great deal of money to be made by having the fastest ship, there was also a huge prestige for the owner. The Tea Races were reported in the National Press and huge amounts of money were wagered with the event being treated like a National sporting event, much like the Grand National today.

The firm of Scott and Linton were contracted to design and build the boat within six months with strict penalties applied for non compliance. The design was a judicious mix of some of the most successful clipper designs and a light composite hull. This was all quite experimental for its time, and as it was being built to Lloyyds A1 Standard ,problems soon arose with Lloyyds wanting the hull to be strengthened. Half way through the build Scott and Linton ran out of money and the job was completed by William Denny and Brothers. When finished, the Cutty Sark maximum logged speed was seventeen and a half knots, so she was not faster that the Thermopylae on paper , but in heavy weather with strong winds she had the edge. So John Willis had been successful in making one of the fastest clipper ships in the world. However his dream of winning the tea race was not to be.

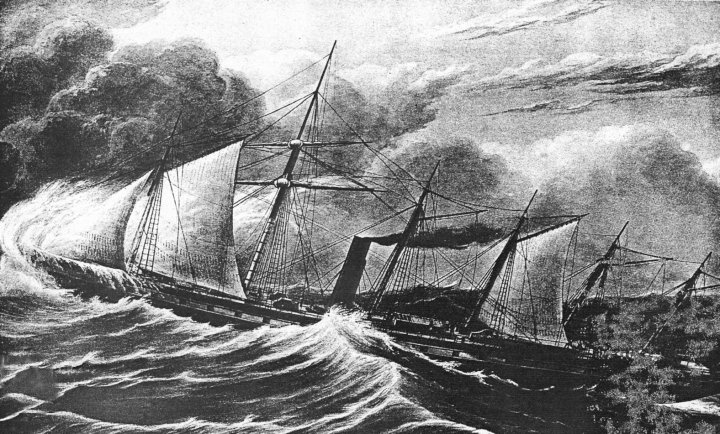

The most famous race against Thermopylae occurred in 1872, the two ships leaving Shanghai together on 18 June. Two weeks later Cutty Sark had built up a lead of some 400 miles, but then lost her rudder in a heavy gale after passing through the Sunda Strait. John Willis’ brother was on board the ship and ordered Moodie to put in to Cape Town for repairs. Moodie refused, and instead the ship’s carpenter Henry Henderson constructed a new rudder from spare timbers and iron. This took six days, working in gales and heavy seas which meant the men were tossed about as they worked and the brazier used to heat the metal for working was spilled out, burning the captain’s son. The ship finally arrived in London on 18 October a week after Thermopylae, a total passage of 122 days. The captain and crew were commended for their performance and Henderson received a £50 bonus for his work. This was the closest Cutty Sark ever came to being first ship home. She was not to make many more Tea races, because by now the Suez Canal had been open for a few years and gradually steamships were taking over the trade and prices were dropping. However there was another cargo that clipper ships could still carry competitively and that was wool from Australia.

It was on this route that the Cutty Sark showed what a wonderful ship she was. On one return trip from Britain to Australia she took 77 days, but on the return only 73 days. No ship was faster, not even her old rival Thermopylae, and for ten years the Cutty Sark was the fasted ship on the Wool trade. In one famous incident in 1889 that caught the publics’ imagination, the passenger steam ship R.M.S. Britannia recorded in her log that when she was steaming at 15 to 16 knots she was overtaken by a sailing ship. That ship was the Cutty Sark.

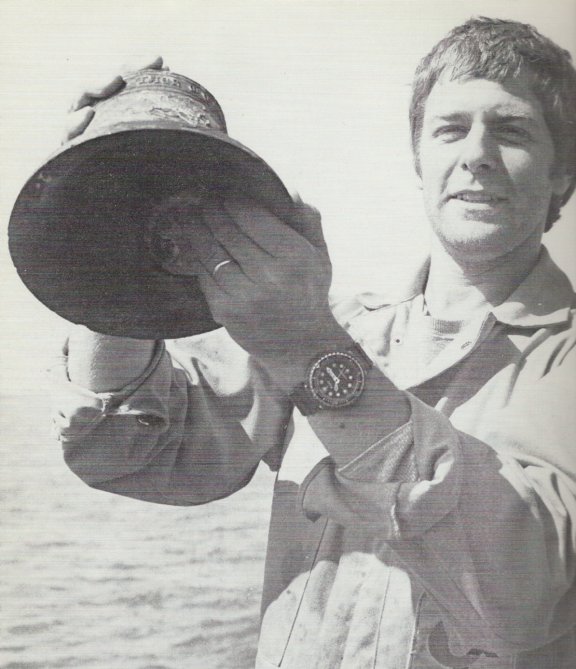

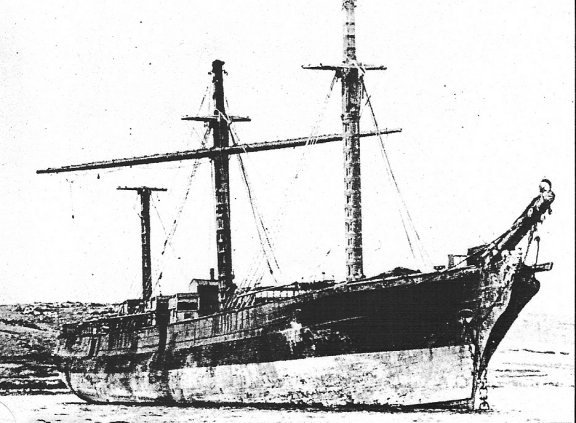

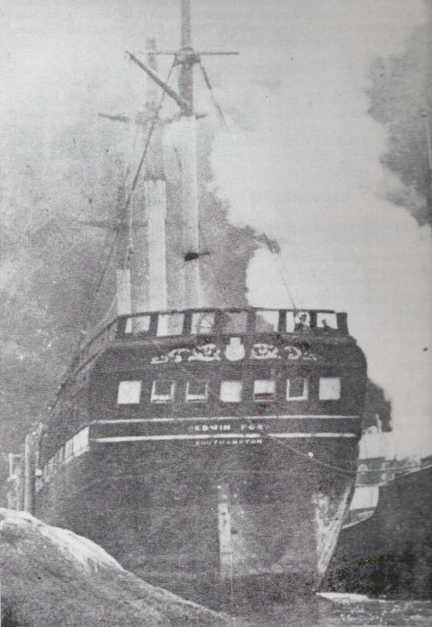

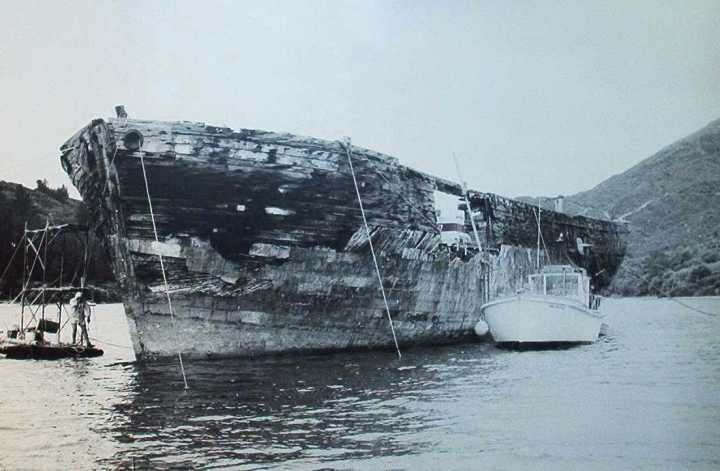

But the era of the clipper ships was coming to an end, and by 1895 only ten remained. The rest had been wrecked, foundered or been condemned. They were to be replaced by huge four masted steel barques with much larger carrying capacities. They would continue in the grain trade well into the 20th century, but for the Clipper ships the bell was tolling. In 1895 the Cutty Sark was sold to a Portugese company and renamed the Ferreira. She carried cargoes all over the world becoming more and more dilapidated as the years passed. In 1922 she put into Falmouth for a short time looking nothing like the famous Cutty Sark. Even so she was recognised by a retired sea captain Wilfrid Dowman, who as a sixteen year old apprentice, had seen her when he was in the sailing ship Hawkdale. Sickened at her sorry state he was determined to save her for the Nation and pursued her back to Portugal where he bought her. Luckily his wife Catherine was a member of the wealthy Courtauld family so there was plenty of money to enable his dream to come true.

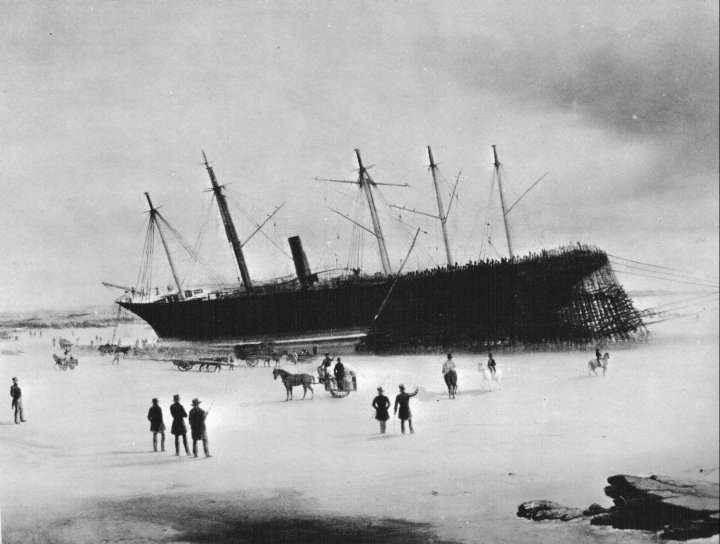

Once back in Cornwall and spruced up, the Cutty Sark became a cadet training ship and during the summer she was also opened up as an attraction, with visitors arriving by rowing boat. Thus she became the first historic ship to open to the public (H.M.S. Victory followed shortly afterwards) since Francis Drakes Golden Hind in Deptford in the 1580’s. When Wilfred Dowman died in 1936 the ship was incorporated into the Thames Nautical College at Greenhithe on the River Thames. However after the Second World War the college obtained a much more modern ship ,H.M.S.=- Exmouth, to carry out her training in, and so the Cutty Sark was seen as outdated and unwanted. The future looked bleak, but at the last minute Frank Carr, the director of the National Maritime Museum, stepped in and persuaded the London County Council, to make a site in bomb damaged Greenwich available for the Cutty Sark. In 1951 the Festival of Britain was in full swing, so the Cutty Sark was given a lick of paint and moored off Deptford to test the public reaction to her full time preservation. People loved her and in two years raised over £250000 towards her conservation. In 1954 the Cutty Sark was floated into her permanent dock at Greenwich and the channel leading to the Thames sealed off. She was safe at last.

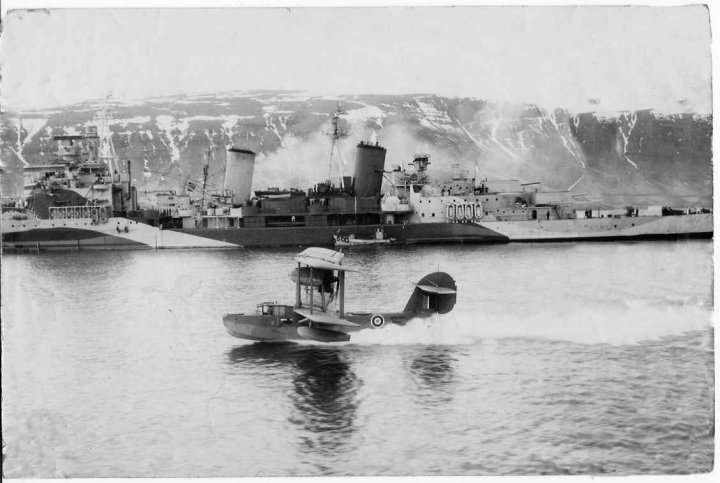

Besides being the last of the Clipper ships her other and some would say more important justification for being preserved was to be a lasting memorial to the Merchant Navy and all those brave men who lost their lives in Two World Wars. By the way I am sure you know this, but the name Cutty Sark comes from the poem Tam O Shanter by Robert Burns and describes a beautiful witch cavorting in a ‘cutty sark’ a sort of short shift. If you drink up the whiskey, it all makes perfect sense.

Opening times, transport links and maps can all be found at the website below.