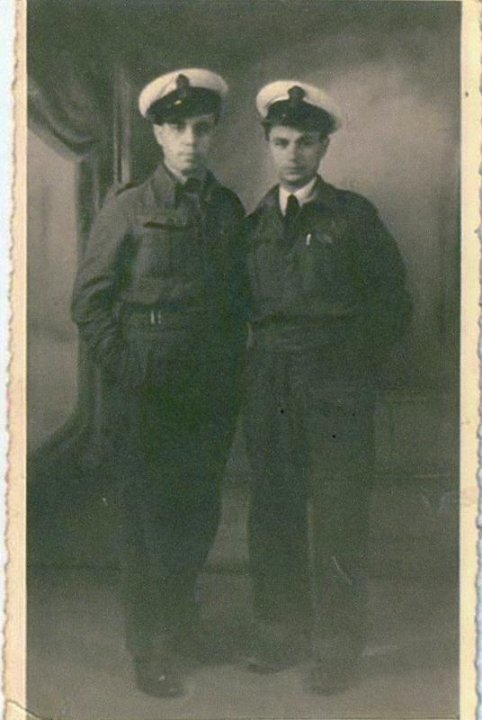

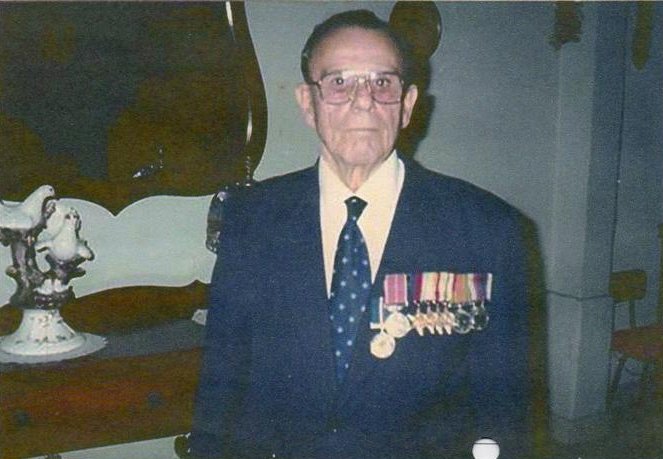

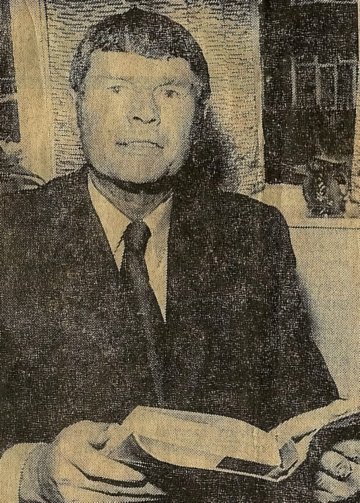

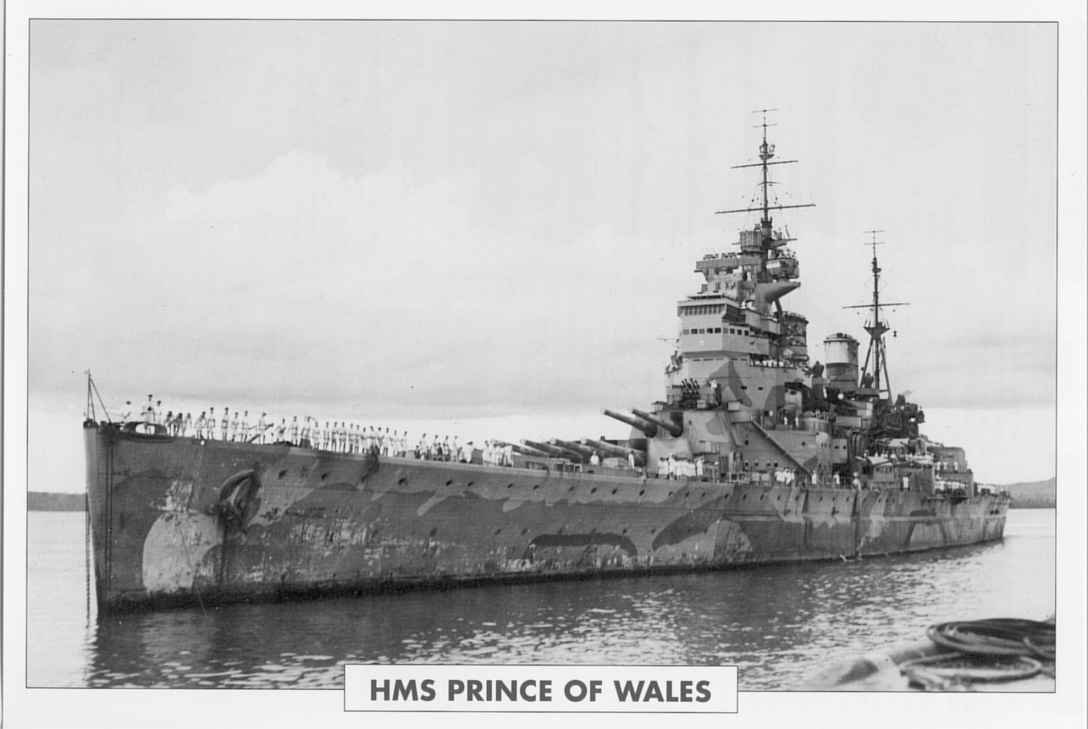

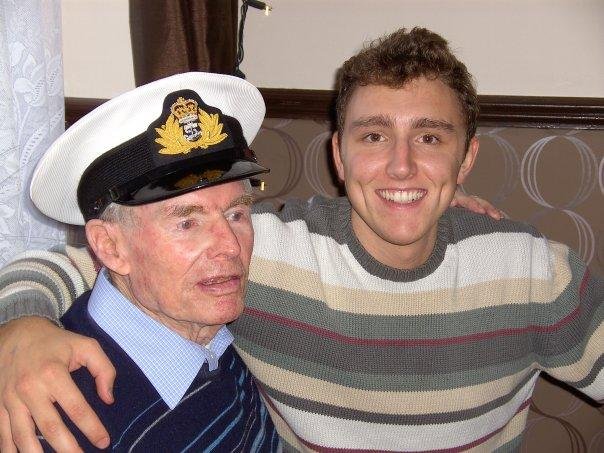

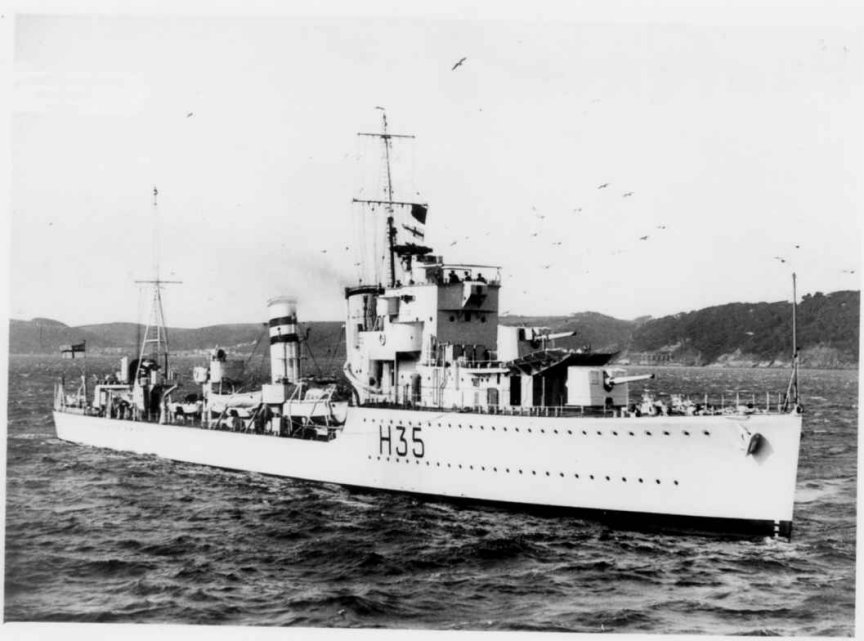

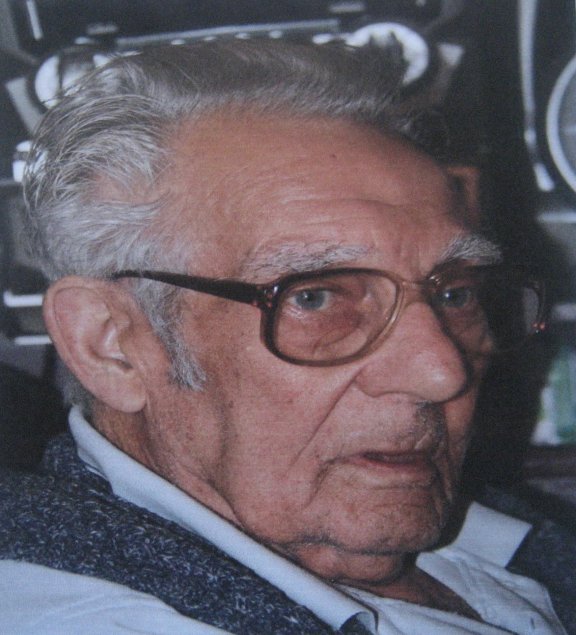

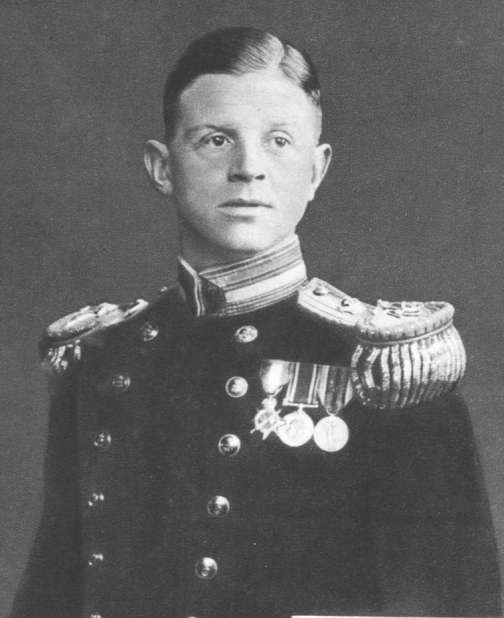

I am extremely gratefull to Ralph Brigginshaw for his ‘memories’ and all his wonderfull photo’s, and to Ron Cope for his hard work in tracking him down. Ralph was born in the village of Chiseldon near Swindon in 1920. He left school at14 which was not unusual in those days. He joined the Navy in July 1935 as a ‘Boy Sailor’ at H.M.S. St.Vincent. He had two brothers who also served in the Navy during the war. On completing his basic training and ‘Signalmans’ course he initially served time on the battleships ‘Rodney’ and ‘Warwick “ a ‘V’ and ‘W’ destroyer during the 1938 crisis.

.

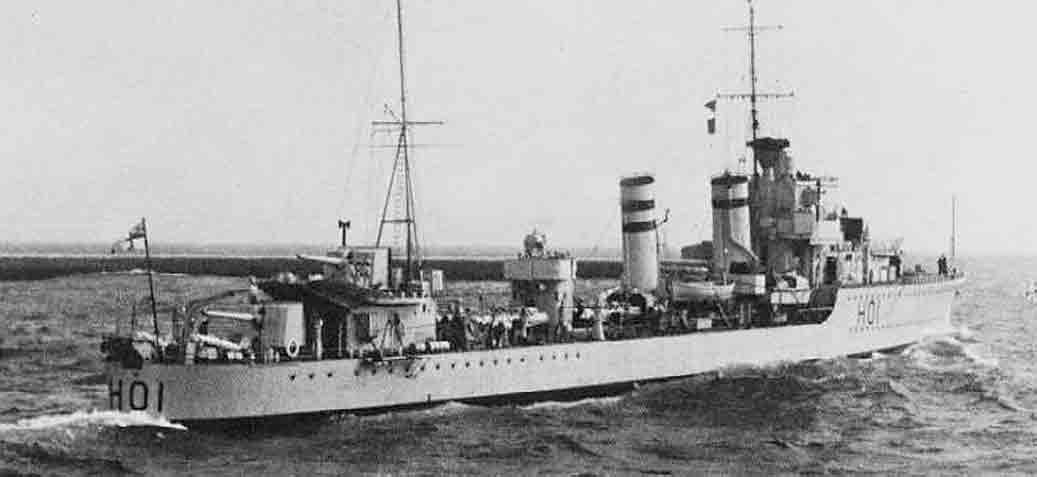

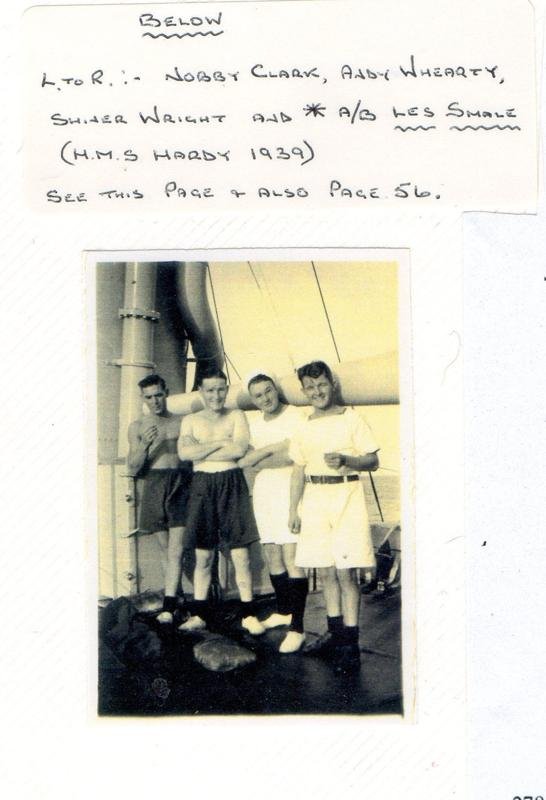

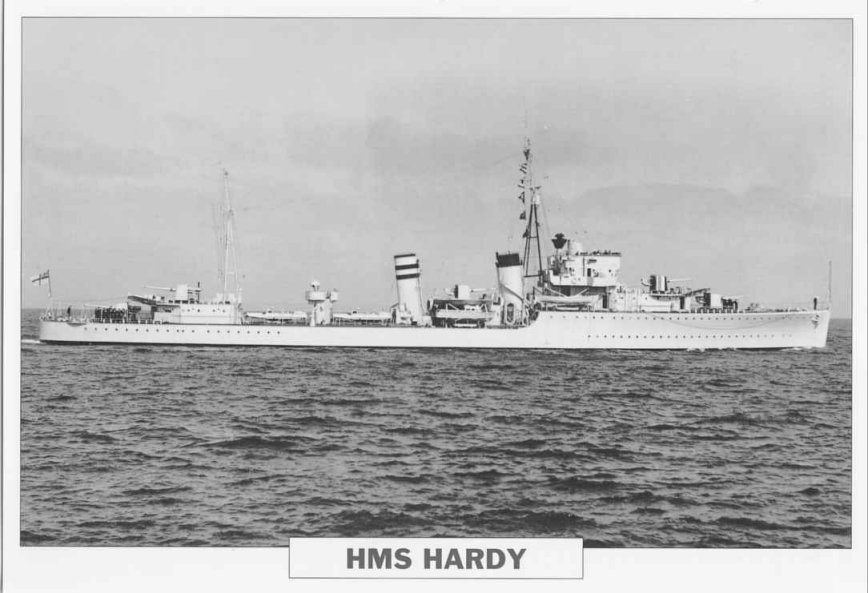

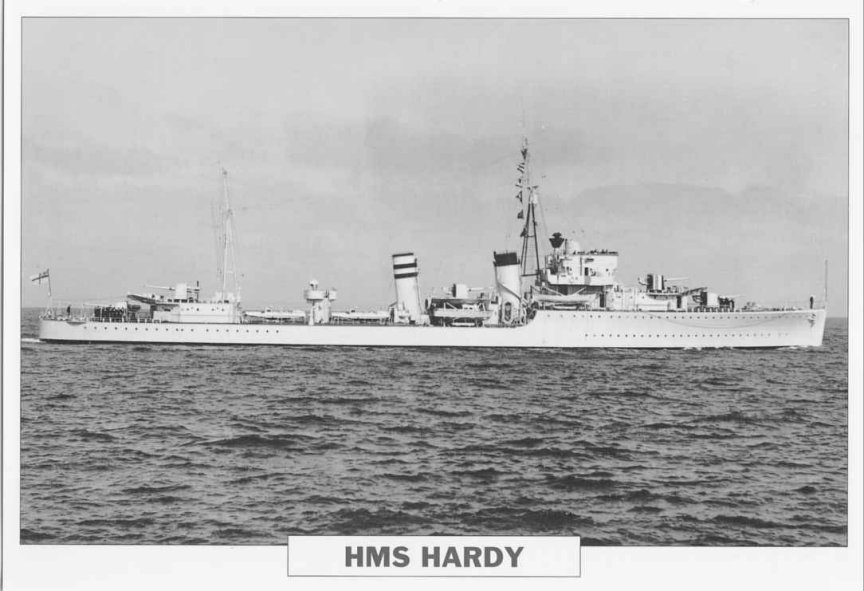

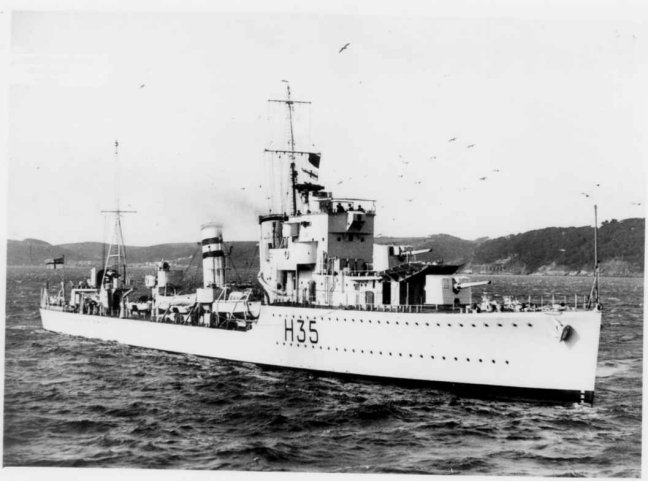

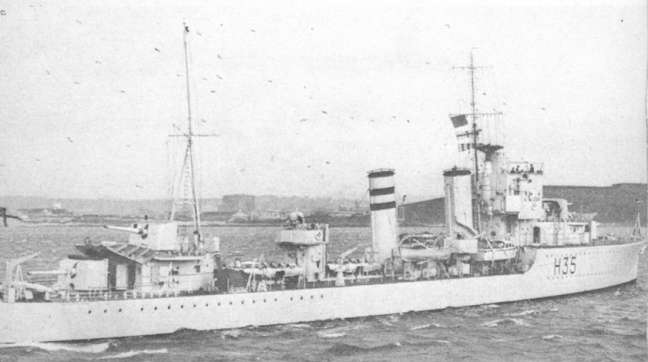

After a spell at Devonport barracks at the age of nineteen he joined ‘Hardy’ and in August 1939 he sailed with the ship to the ‘Med’. The ship’s deployment there just prior to the outbreak of war has previously been described by other crew members.

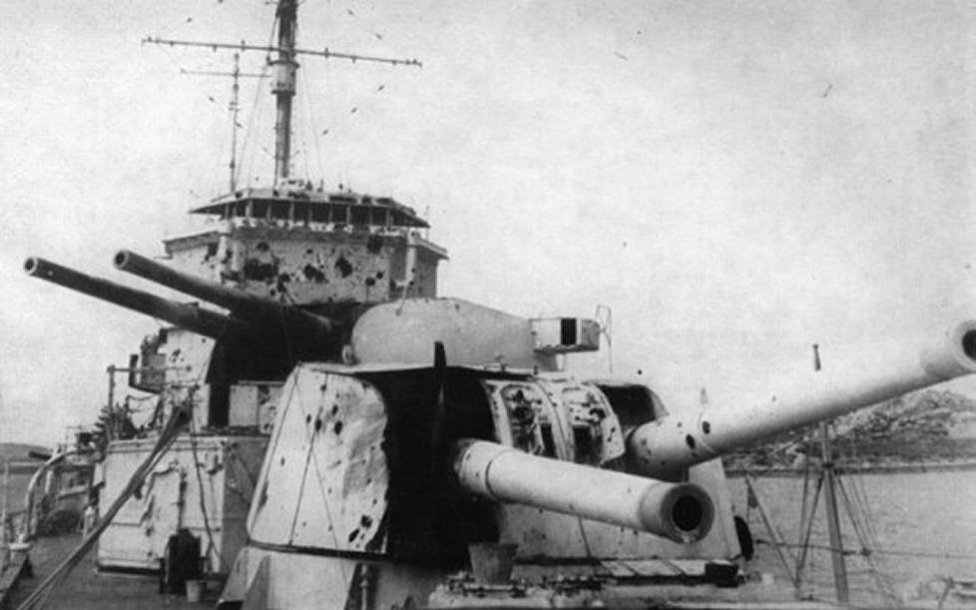

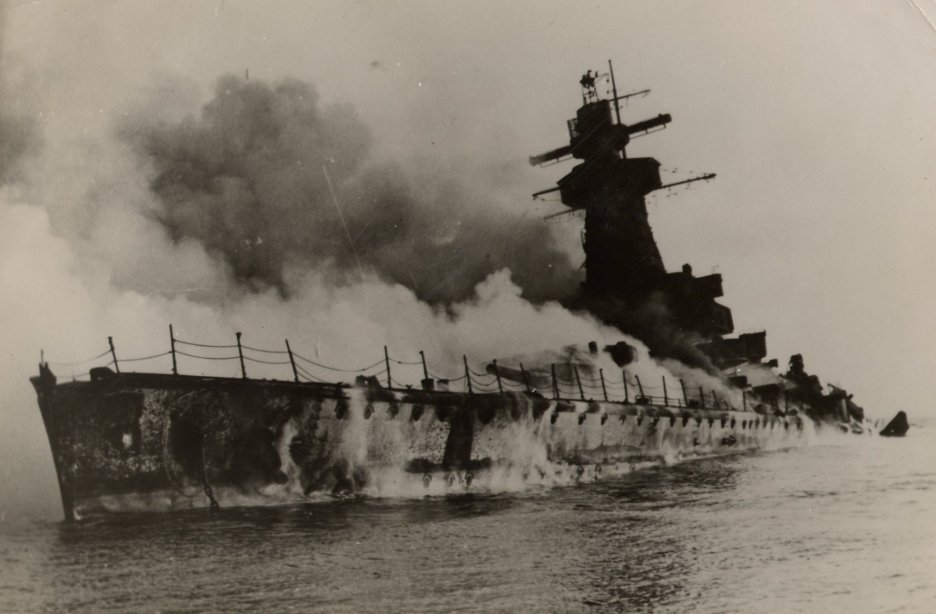

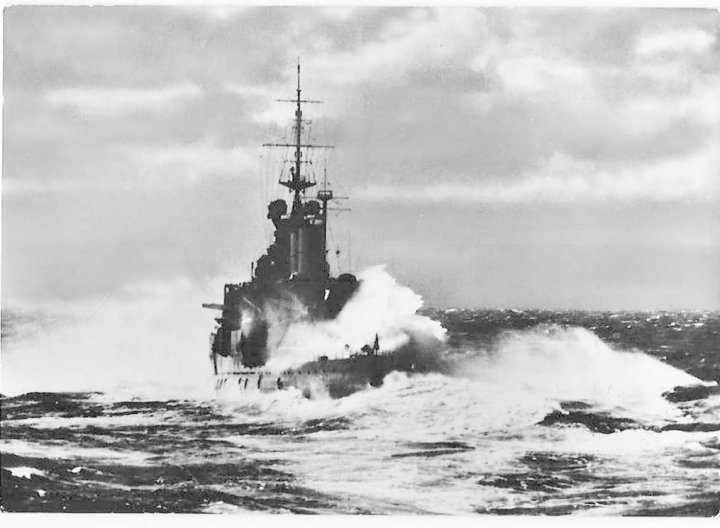

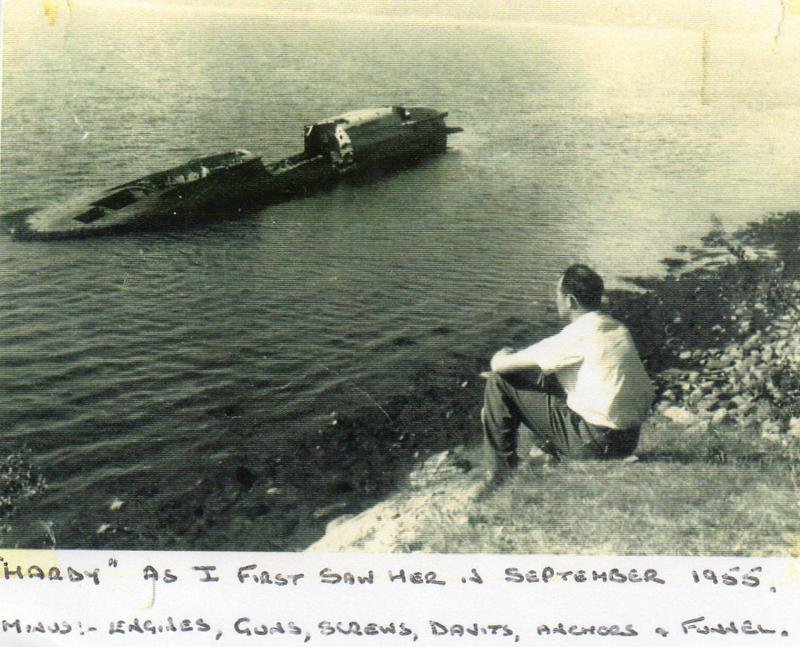

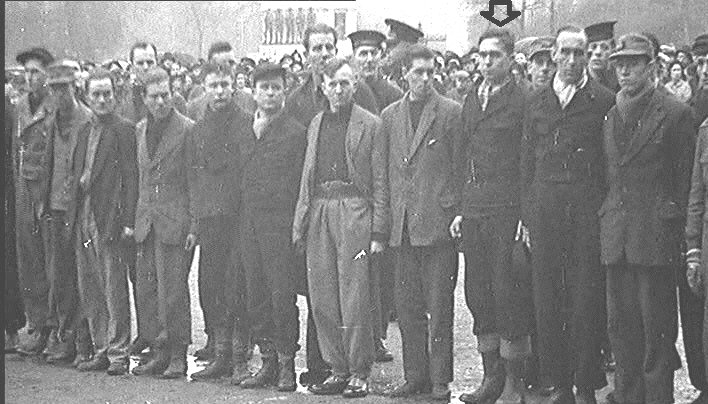

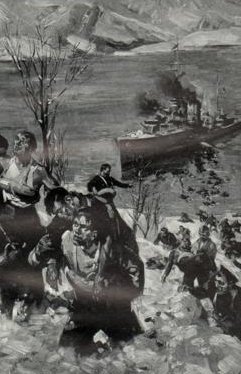

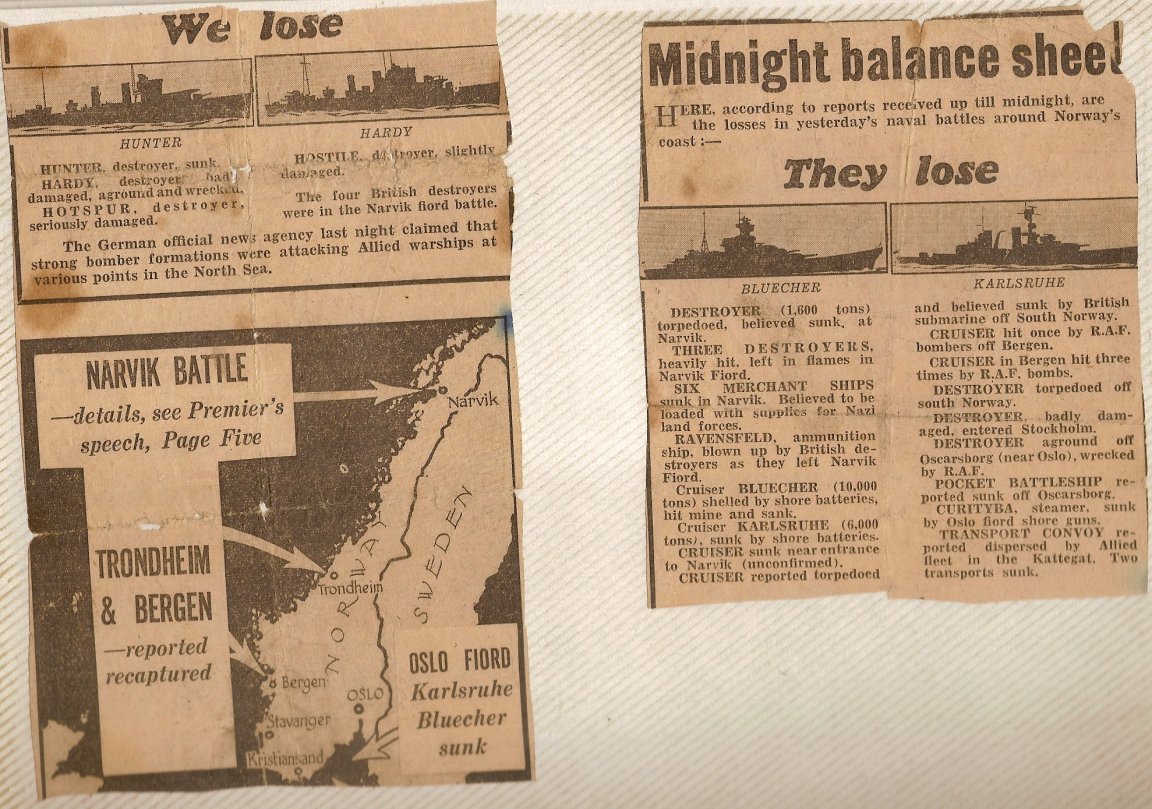

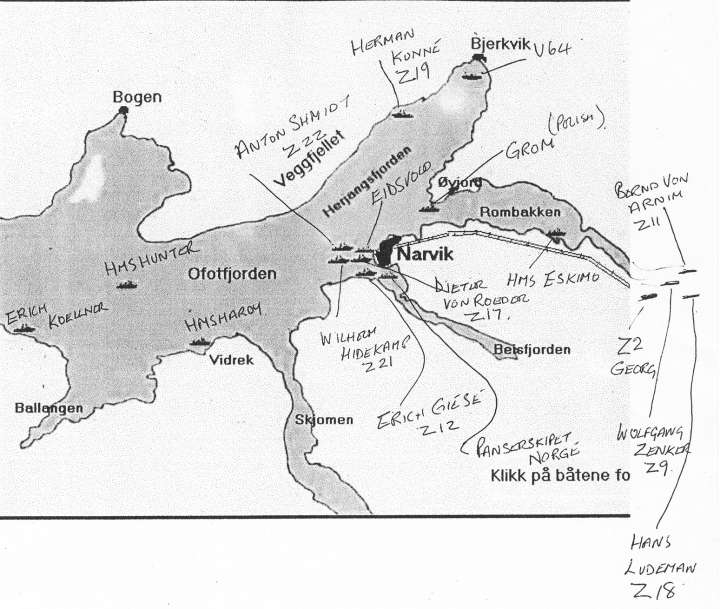

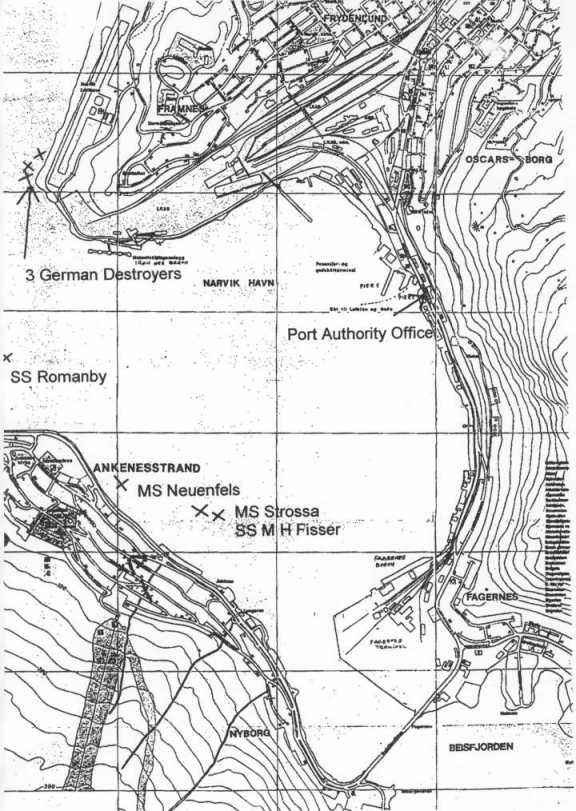

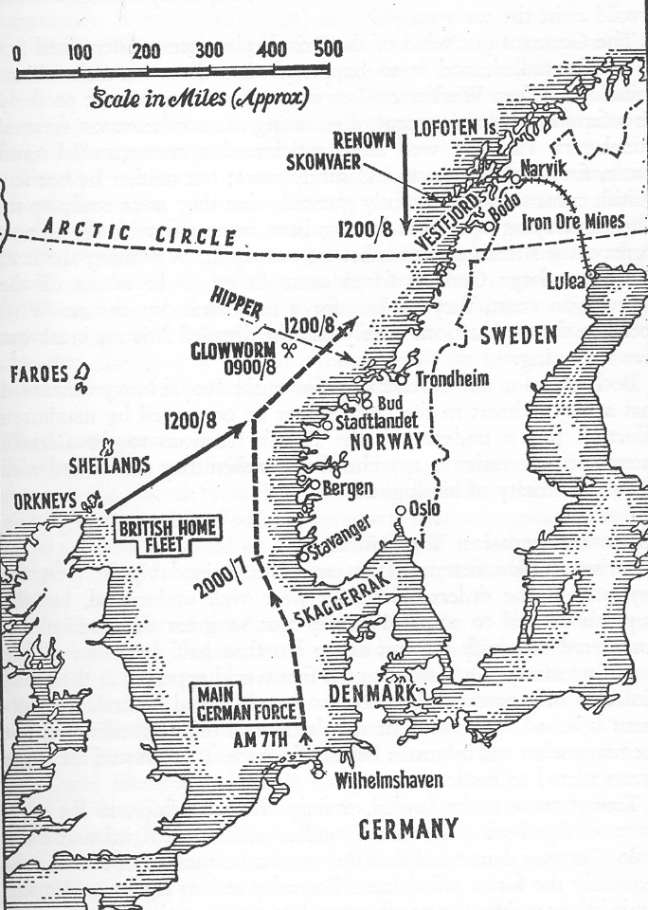

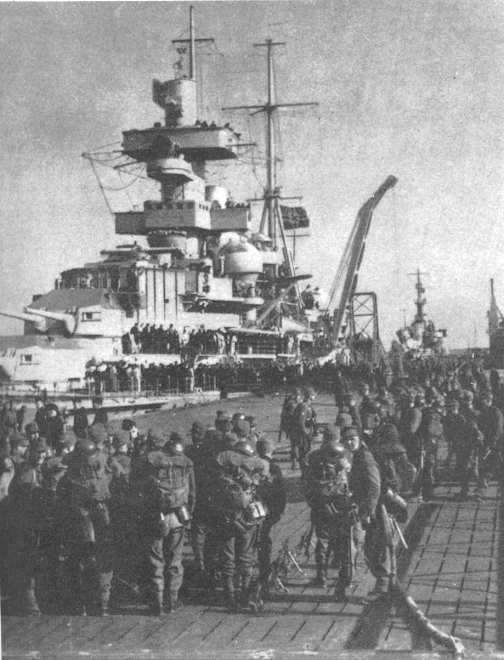

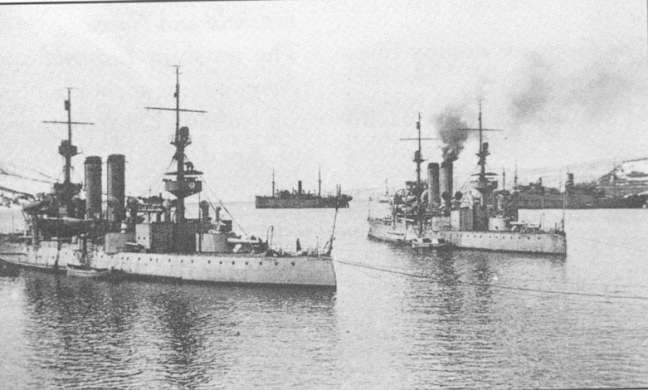

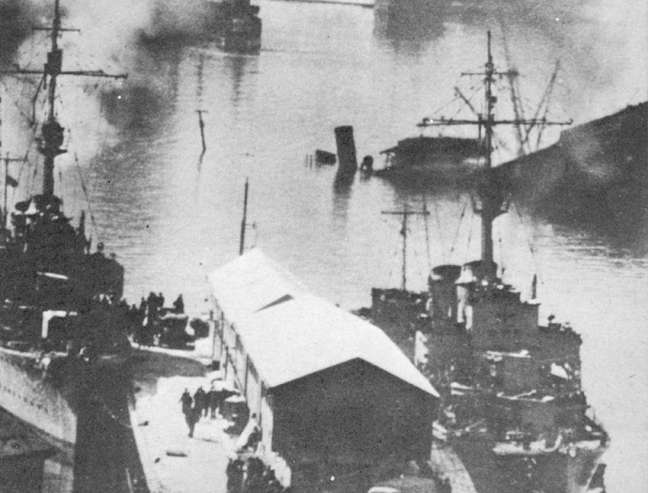

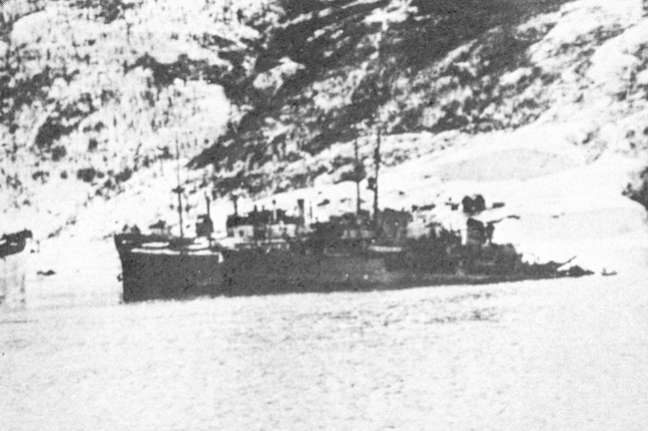

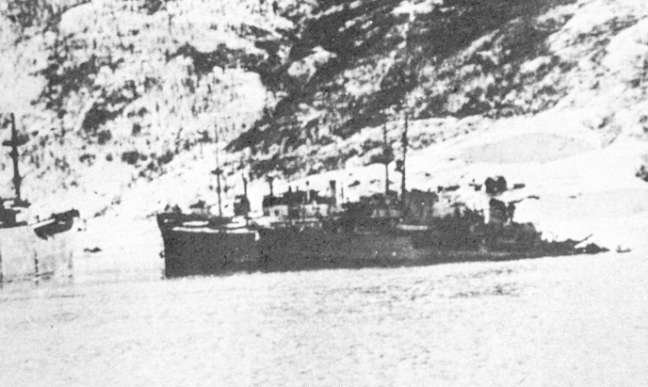

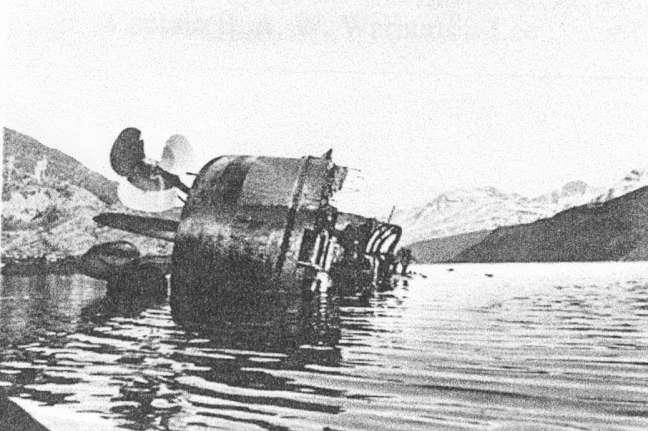

When ‘Hardy’ returned to Devonport after “a mad rush back from Freetown” in West Africa, leave was granted. This was February 1940 and going to be the last he saw of his family for a considerable time. Leave to all watches completed ‘Hardy’ sailed for Scapa Flow. It was here that all the crew were given the opportunity to write their last letters home prior to going on operations in the North Sea and eventually ‘Narvik’. The ‘Hardy’ finally arriving at Narvik, Ralph recalls, “my action station was on the flagdeck and I remember the first run into the harbour. A lot of damage was done but I noticed two torpedoes missed their targets. It was exciting having a good view of the action from the flagdeck”. He goes on to say, that “later on the third run as we turned to starboard I saw three German destroyers approaching also to starboard. It was then a shell came through the flagdeck and the wheelhouse next to us. I remember thinking ‘what a hell of a mess’. I was hit in the centre of my back and arm by shrapnel. I realised I had no use of my arm. My mate Signalman ‘Ginger’ (Cuthbert) Turner had also been wounded.

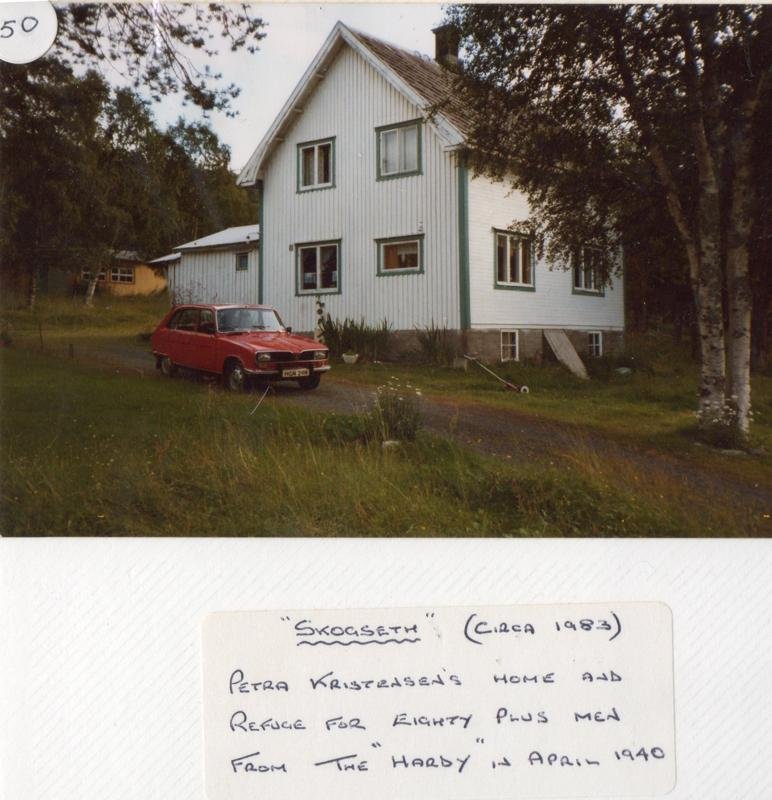

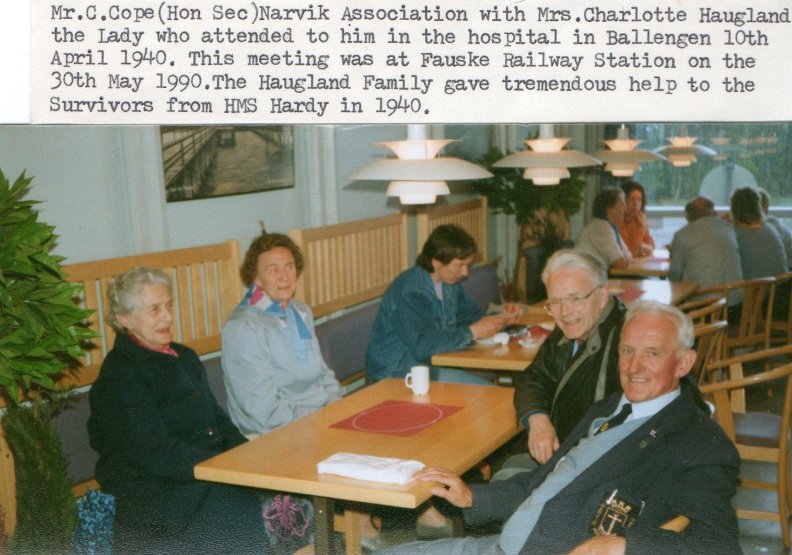

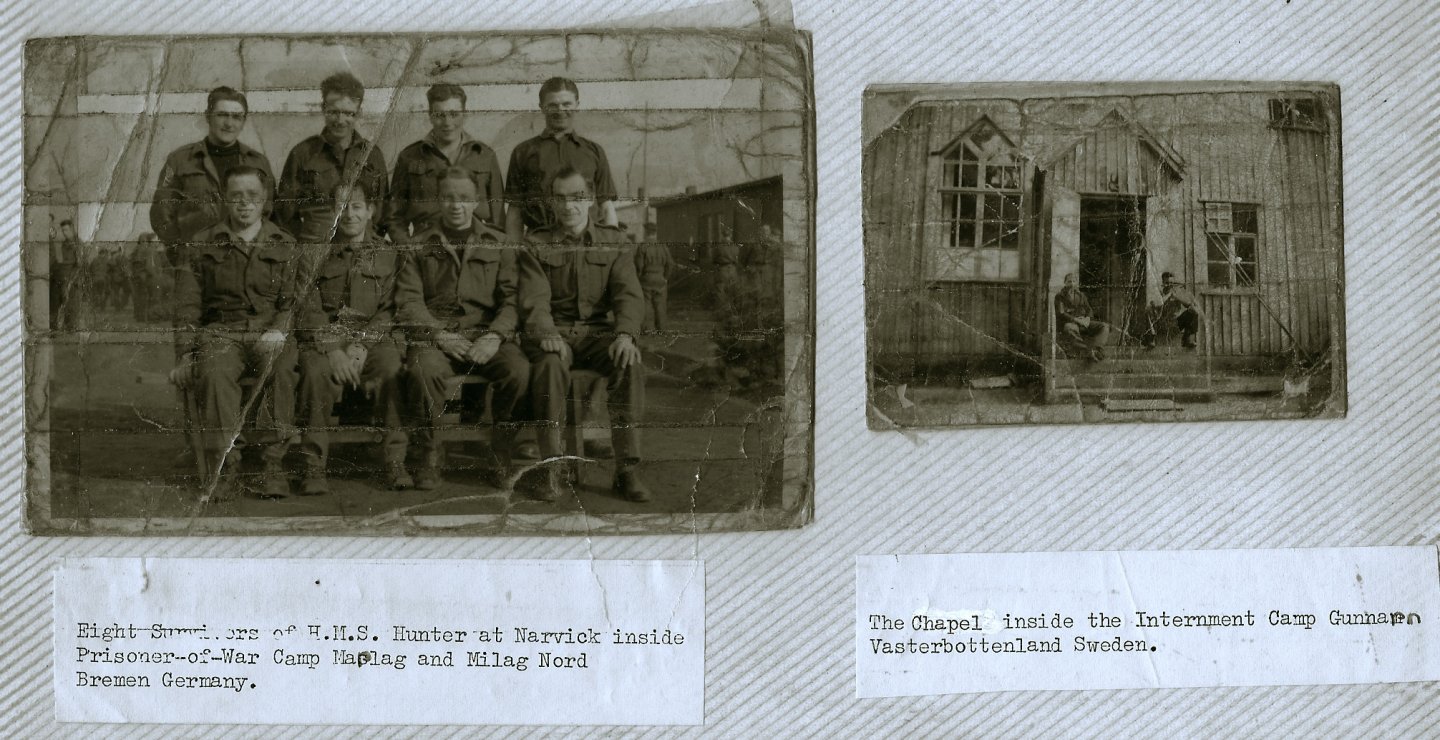

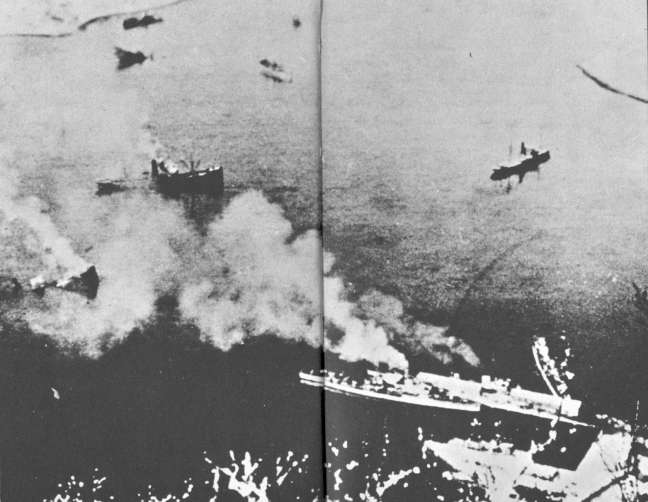

He continues to describe that both of them with other wounded men were eventually put into a ‘whaler’. However, he states, “it was full of holes and sank. I was helped out by Yeoman Thatcher. I said ‘I’ve had enough’ but he replied, ‘don’t be bloody silly’. I was then unconscious for three days. I had been taken to a hospital at Ballangen and was awakened by a loud bang”. (‘Compiler Ron Cope’ – this was probably caused by the sixteen inch shells sent into Narvik harbour by ‘Warspite’ in the 2nd Battle on 13th April). It was planned that the more seriously wounded men, including Ralph, were to be taken to the ‘Lofoton Islands’ to be picked up by HMS Penelope, a cruiser, instead of the destroyers. However, previously the Penelope had hit a rock and was then needed to be towed by ‘Eskimo’. When the two ships arrived, Penelope would not take them on board and after a few discussions it was decided the wounded men should go to a hospital ashore. This was the Gravdal Hospital (Gravdal Skyehus) on the island of Vestvagey in the Lofoton.

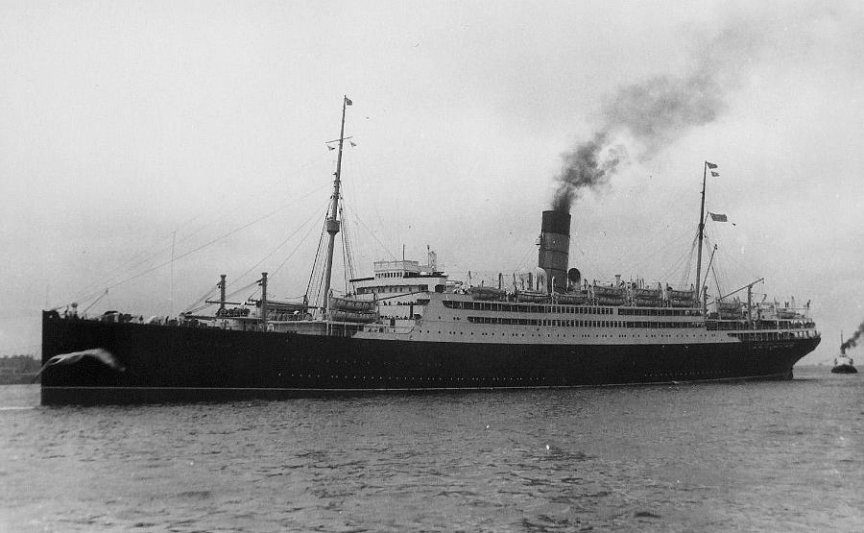

Ralph remained a patient there for six weeks. He recalls, “I was then cared for by a family. Later, some of the lads came along and suddenly told me to get ready for transport in a local fishing boat. I spent my 20th birthday cruising up the fjord”. He then arrived at ‘Tromso’ a few days later, just in time catch the last hospital ship ‘Atlantis’ leaving for Britain. He continues, “I arrived at Liverpool about the 9th June, but because of a relapse, I needed to be stretched ashore”. However, Ralph’s journey was not quite over having then to endure a train journey to a hospital near Glasgow.

“Then two and half years of changing from hospital to hospital, including Winwick Hospital, near Warrington in Lancashire. I had another hiccup there. They used a bone from one leg to patch up the arm and when the plaster was taken off, sent me to a hospital near Bristol for recuperation. Unfortunately they left me alone on the station with a full kitbag. As I lifted the bag to put it on the rack in the train, I heard and felt a big crack. On arriving in the hospital they confirmed the arm had been broken again. So within 48 hours I was back at Warrington. They then took a bit of bone from the other leg and patched me up again”.

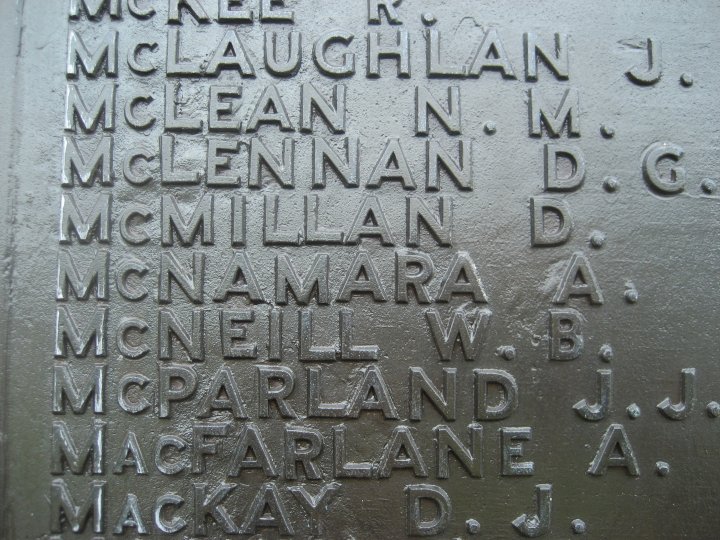

By July 1940, Ralph had lost touch with his shipmate ‘Ginger’ Turner. So he decided to write to him. Sadly, Ralph received a reply from Ginger’s mother to say that a week before his own discharge from hospital he had gone sailing nearby with a nurse. The boat had overturned and he had drowned.

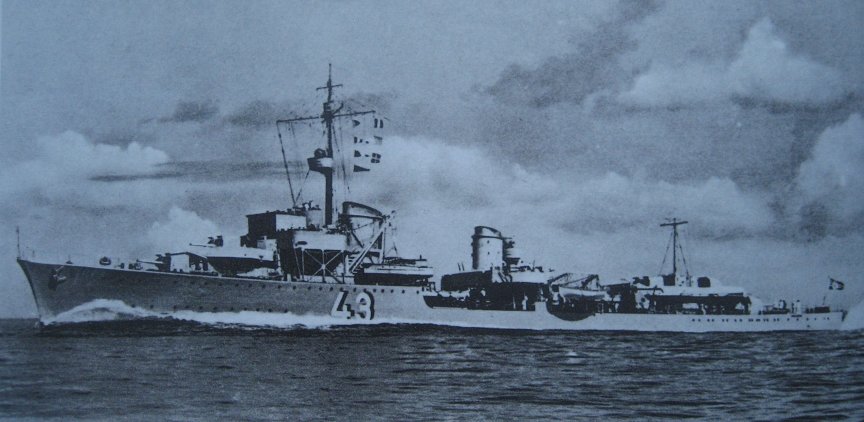

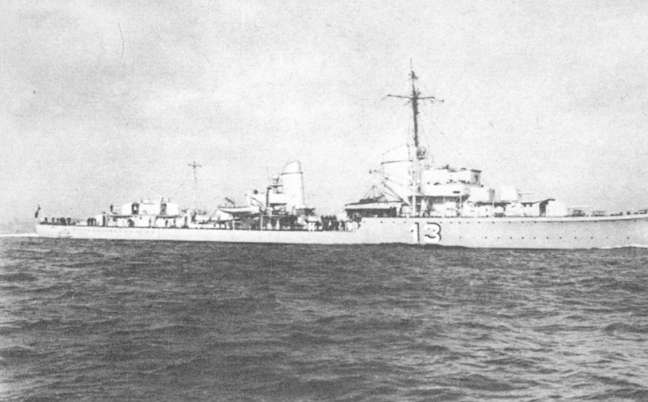

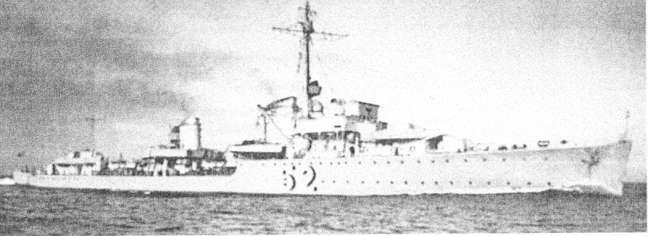

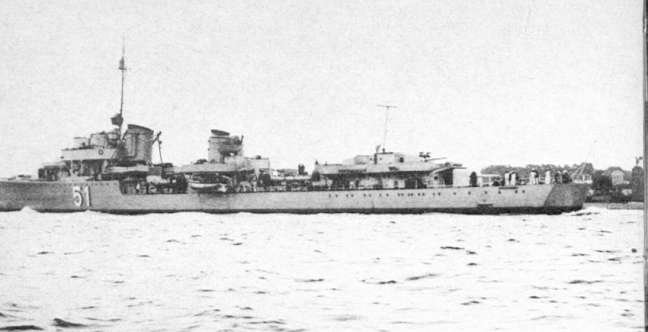

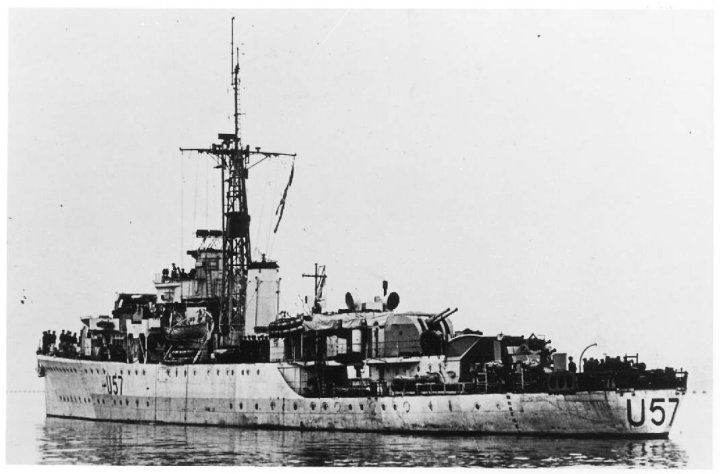

Ralph was finally discharged from hospital in October 1942 and drafted back to Devonport barracks. He was very pleased to be drafted to a ship within a month. “I was sent to a new ‘Sloop’ HMS ‘Cygnet’ who had just been built at Birkenhead. We did our ‘acceptance trials’ in the Clyde and then sailed to Tobermoy for our final sea trials. Unfortunately, she ran aground on entering the harbour. I was then loaned to the ‘Black Swan’ for the North African ‘Landings’. After awhile I returned to ‘Cygnet’ in time for the Sicily ‘Landings’. From then I had a few months in the North Atlantic before going to HMS Mercury for the ‘Yeomans’ course. On completion, whilst waiting for transport to Canada to pick up a new ‘Algerine’ minesweeper I spent a spell on a Polish destroyer at ‘Slapton Sands’ in South Devon . This was in readiness for the ‘D Day’ Landings”.

Ralph remained in the Royal Navy till 1950 leaving as a ‘Yeoman of Signals’. However, he still had problems with his back injury. On his release to ‘Civvy Street’ initially he was manager for a Radio and Electrical Shop in Brighton. He was later transferred by the firm to Crawley. During which time he completed a correspondence course in ‘electronics’. Once attaining qualifications he secured employment at Gatwick Airport as a ‘Radio and Radar Engineer’. In between times he married Betty in 1957.