The advent of the First World War saw many new innovations, the most profound being the advance of the aeroplane, from something of a music hall joke to a serious fighting machine.

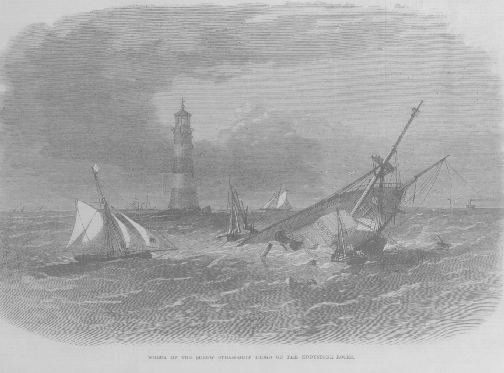

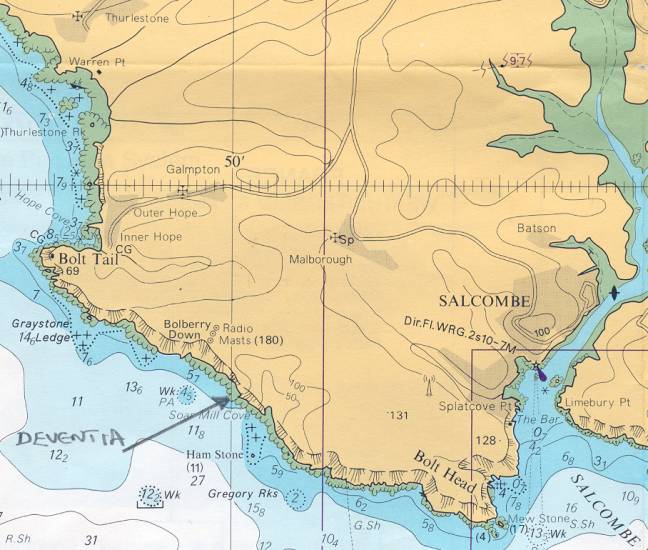

The military were not slow to see its advantages and for a time its development overshadowed other even more warlike machines. One such was the evolution of the submarine. The British, with characteristic stupidity, had condemned underwater warfare as tantamount to cold-blooded murder, and definitely not sporting. The Germans however knew a winner when they saw it, and churned out hundreds of the deadly craft and soon were gaily sinking thousands of tons of British shipping while the Navy, who had never had any qualms about undersea warfare, murder or not, pointed the finger at the politicians. In the meantime the U-boats had it all their own way, and in an age before the wolf packs had been invented they sectioned off their killing grounds into huge boxes so that each submarine had a set target area. One of the best was the box that encompassed both the Eddystone and Start Point. Nearly every ship that passed up the Channel had to come through this box, and on the night of December 18 1917 the armed British merchant steamer Riversdale was to be no exception.

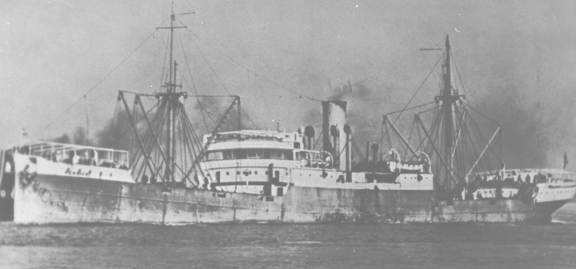

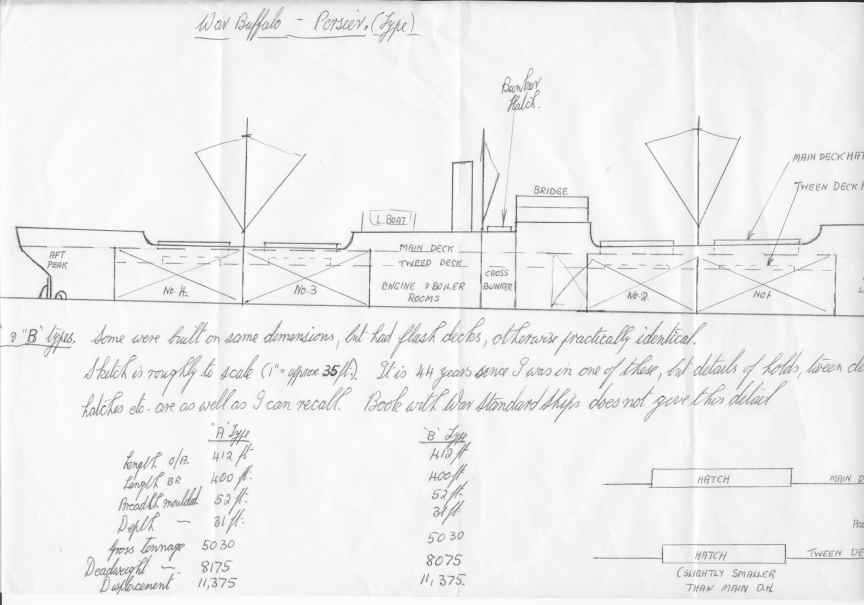

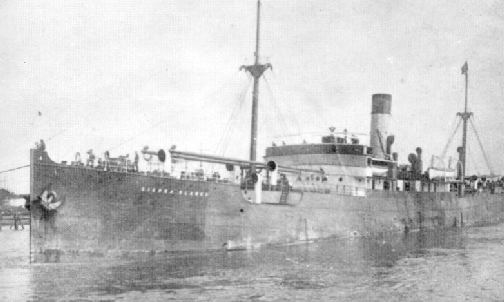

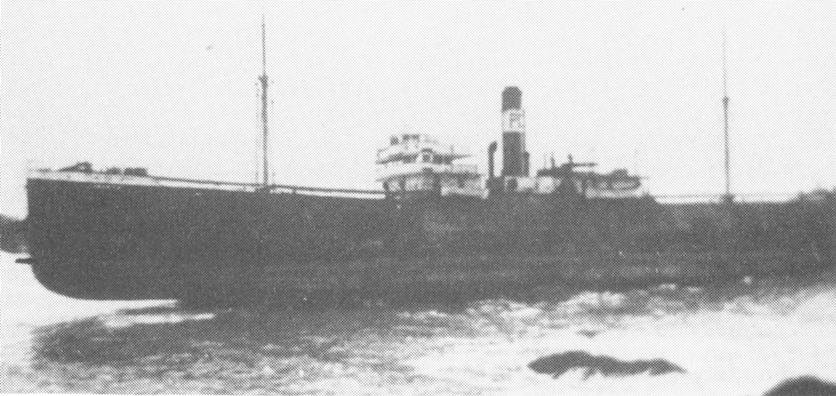

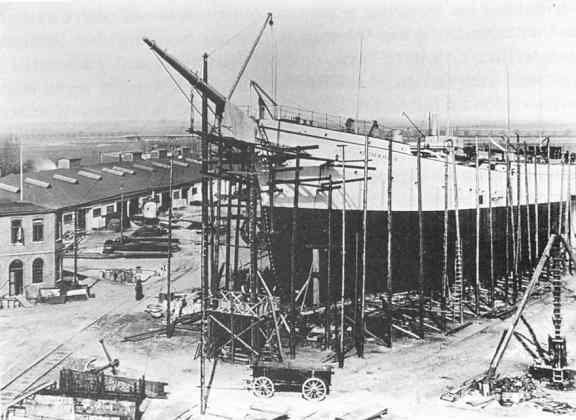

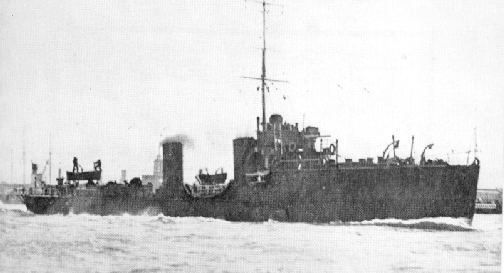

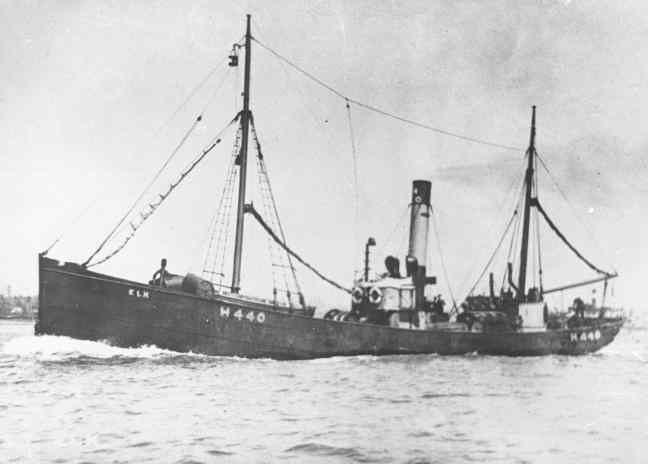

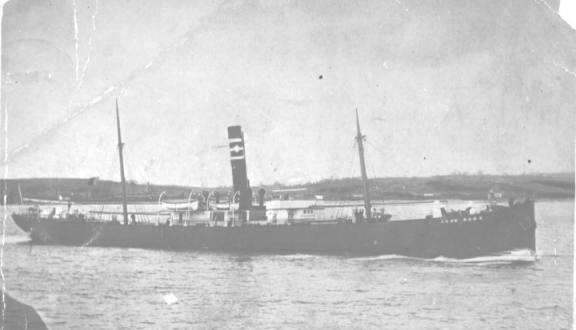

Built in 1906 by J Blumer & Co of Sutherland, the Riversdale was 317 feet long with a gross tonnage of some 2805 tons, and was en-route from the Tyne to Savona in Italy loaded with a cargo of coal. Lurking in her path was the German submarine U.B. 31 commanded by Oberleutnant Bieber. As the Riversdale came abeam of the Start Light, Bieber picked up the noise of her single crew and rose to periscope depth to have a look. There in the pale moonlight he could see the cargo vessel plainly silhouetted, steaming slowly towards him. As the Riversdale came within range, Bieber loosed a torpedo which struck the vessel, causing such an explosion that Bieber, confident the Riversdale would sink called off the attack and hightailed it north east towards Dartmouth, where he caught up with another collier, the Alice Marine, and sent her to the bottom.

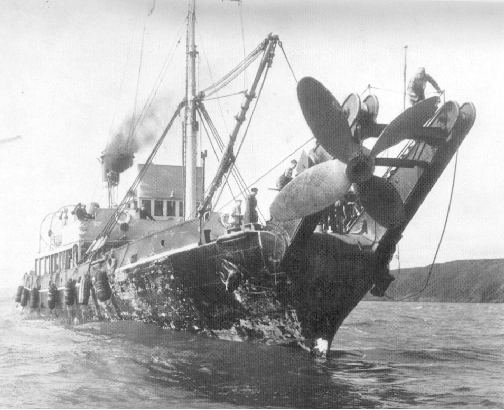

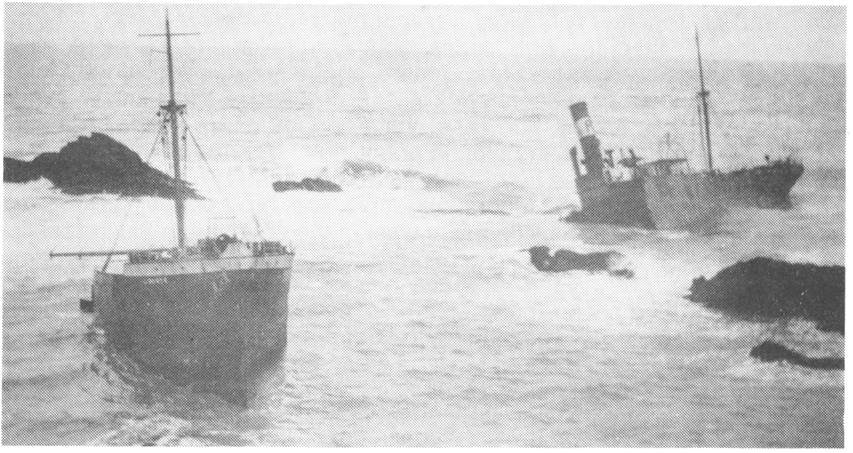

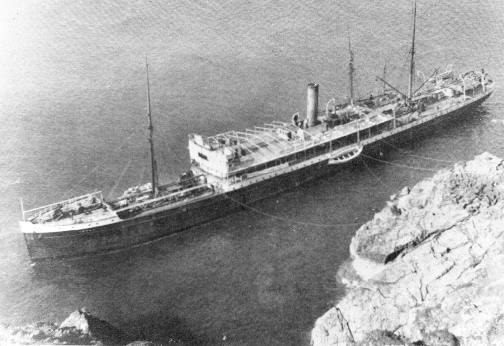

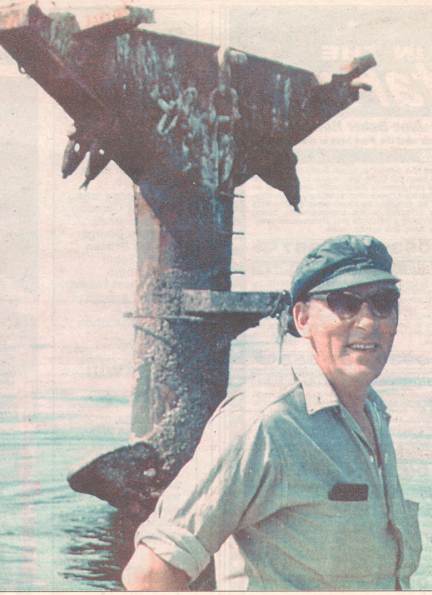

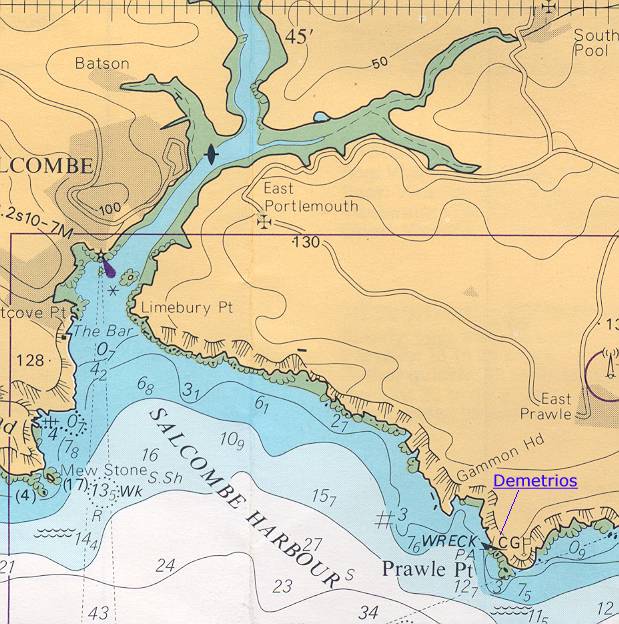

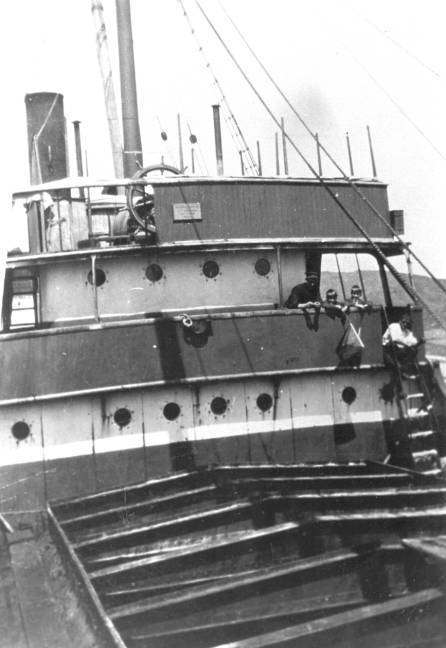

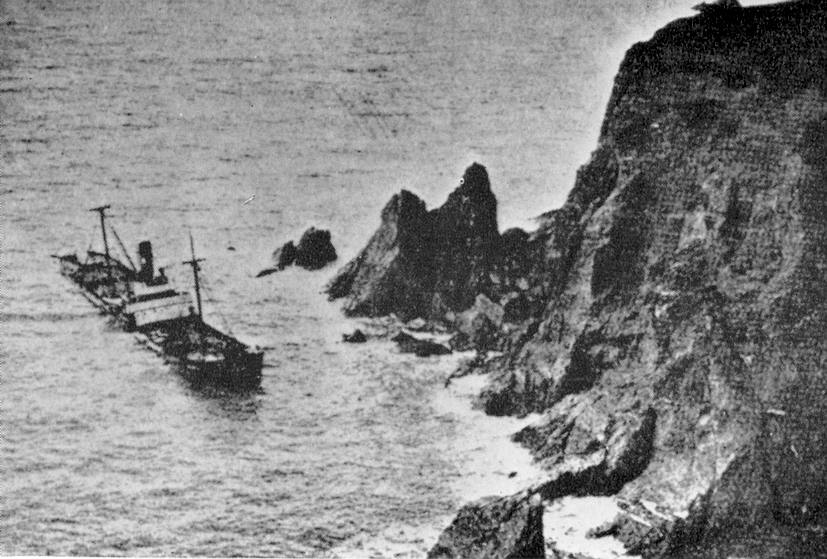

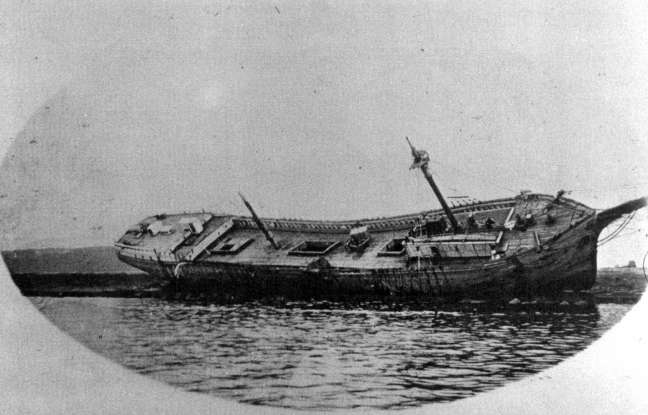

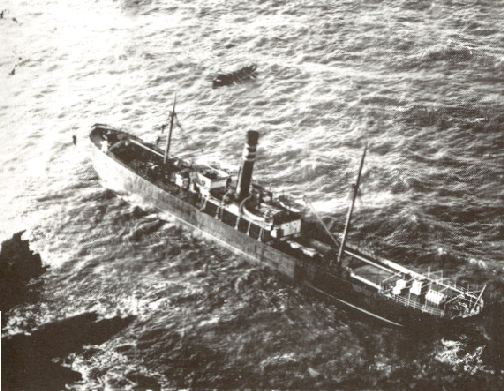

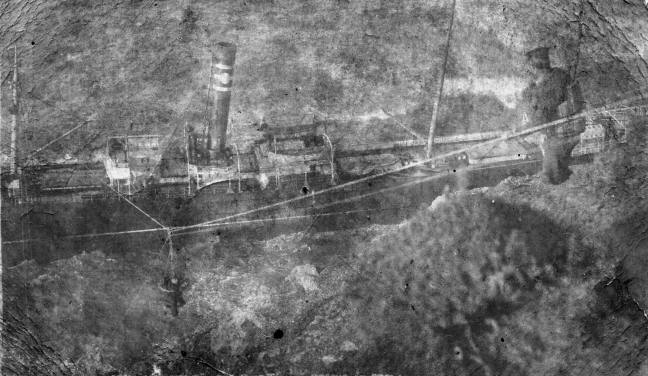

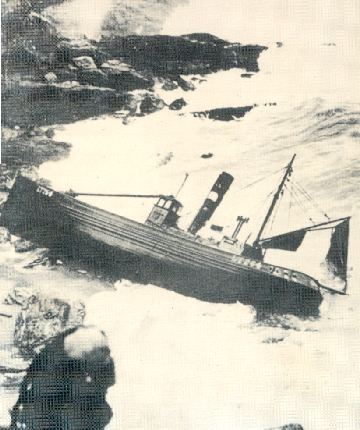

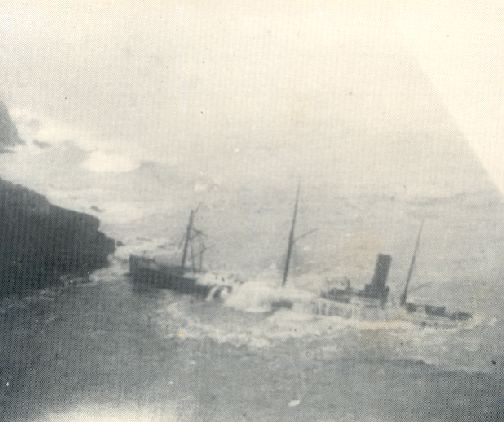

Meanwhile the Riversdale had surprised herself and her crew by staying afloat and her skipper, Capt. Simpson, was now battling to get her safely to the shore. In this he succeeded, finally running her aground near Prawle Point. Luckily the weather was in his favour, and apart from one crewman lost in the initial explosion, all the rest of the crew were saved. Salvage experts quickly arrived on the scene and soon decided that with a bit of effort the Riversdale could be saved. To this end bulkheads were shored up and compressors were installed to get rid of the water and keep a check on leaks from the patch that had been hastily cobbled together around the torpedo hole. Tugs were sent for, towing arrangements made, and with a mounting sense of confidence the Riversdale was pulled off the rocky shore. She came off without too much trouble, but before the vessel had gone more than a thousand yards the patch blew off and the Riversdale gently sank, nice and upright in about 42 meters of water. As she hit the bottom her bow broke away and in later years her superstructure was wire swept and dispersed.

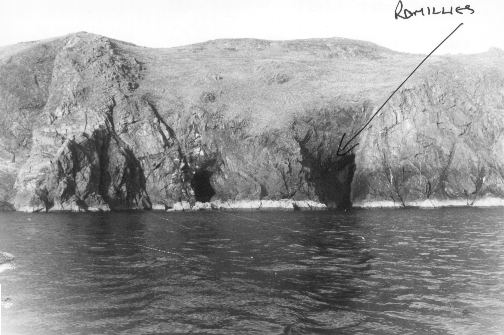

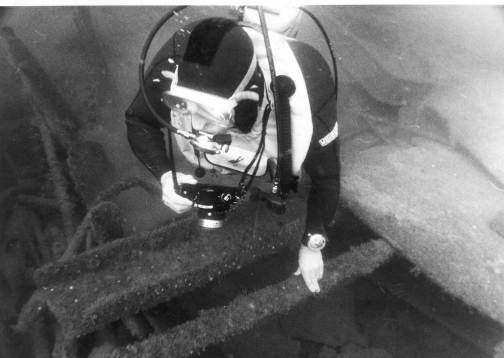

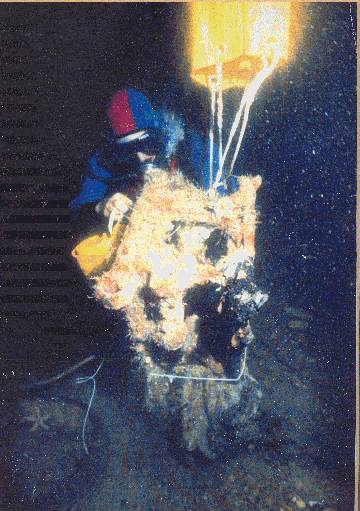

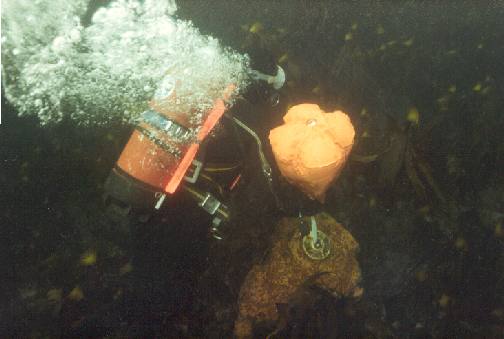

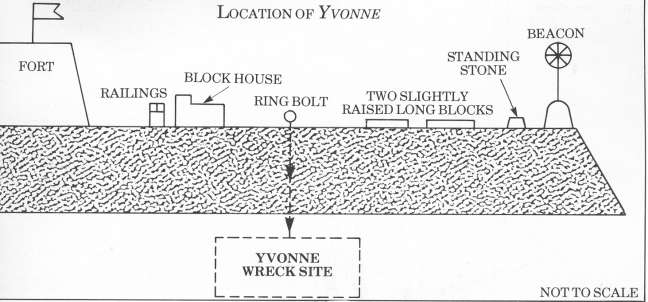

Even with all the wire sweeping, this wreck still sits up 45 feet or so from the seabed and so is quite easy to find once you have sorted out where the marks for the marks are. This bit of coast is rather bland, so study the photos carefully and then confirm with your echo sounder. If you are hooked, then you are on it because there is nothing else in the area and the seabed is just sand. The visibility on the Riversdale is usually very good, 20 to 30 feet being the norm, and because it is in a relatively sheltered area it can be dived on most occasions. However the tidal streams in this area are very strong, so slack water is by far the best time to dive her. Once on the wreck you will find that in someways it is very reminiscent of the James Egan Layne a few years ago. The wreck is virtually still intact and has massive holds that you can swim into just like the Egan Layne. Since it is a good bit deeper however, it is not as light inside the holds and your exit points are limited, so distance reels are very necessary. At the stern the wreck still has its great iron propellor supported by huge brackets, and it is here that you probably get the best indication of her size as you swim from the deck, down over the stern to the prop and the sand below. Scattered around the wreck is part of its cargo of coal, and local divers quite often raise some in sacks for their own use. A nice bonus this, I always think, as this type of coal always seems to burn with a weird green and blue flame. Smashing on a dark, cold night.

The fish life on this wreck is not as prolific as others in the area, maybe because it is heavily fished by anglers. Once again there are a lot of old lines hanging around, so make sure that your knife is sharp. All in all the Riversdale is one of my favourite ‘deep’ wrecks because it is easy to find, nice and intact, and has that feel about it that makes you think you are going to find something really nice. To date no such luck. But one day, who knows?