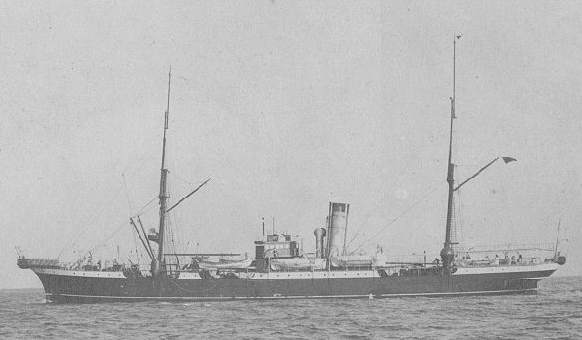

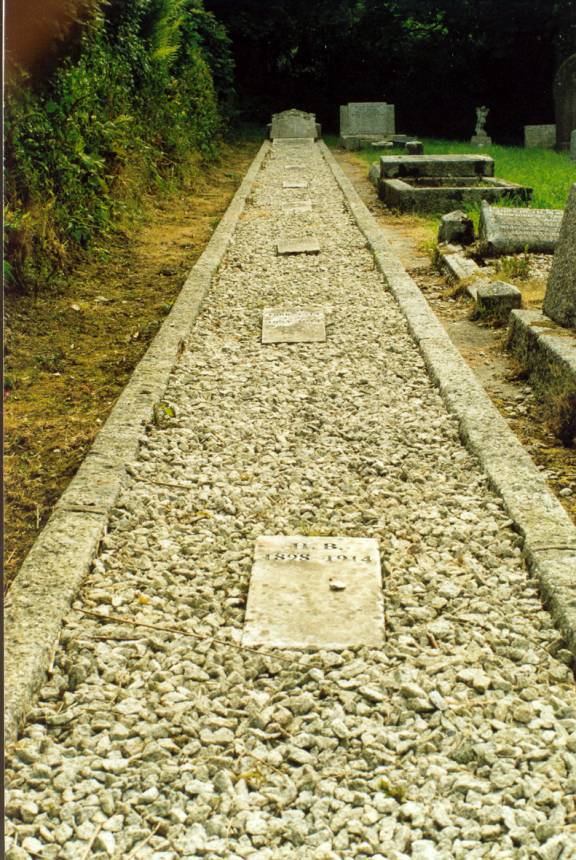

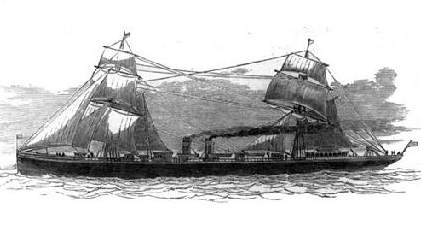

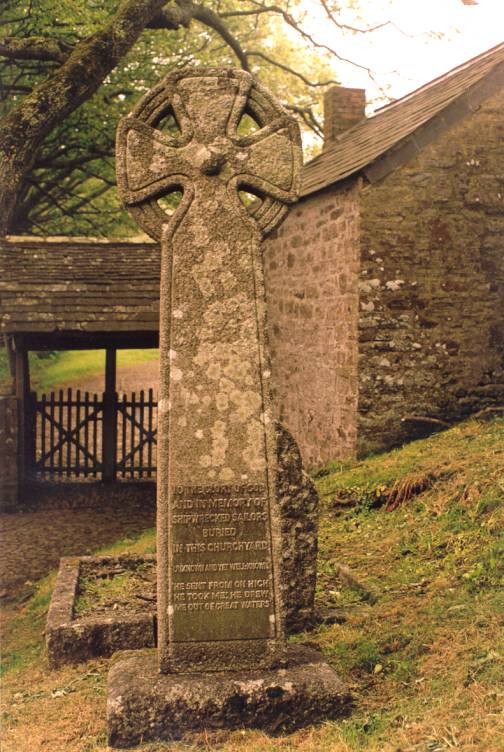

Set into the wall of the jetty at Margate is a marble tombstone to nine Margate men who lost their lives on the Lugger ‘Victory’ on January 5th 1857. The ‘Victory had been to the aid of the crew of the American sailing ship Northern Belle. The disaster prompted a silver medal to be struck and given to those involved in the rescue, by Franklin Pierce, the President of the United States of America.

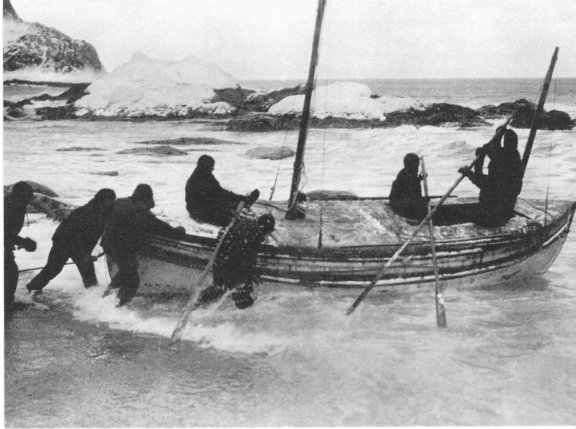

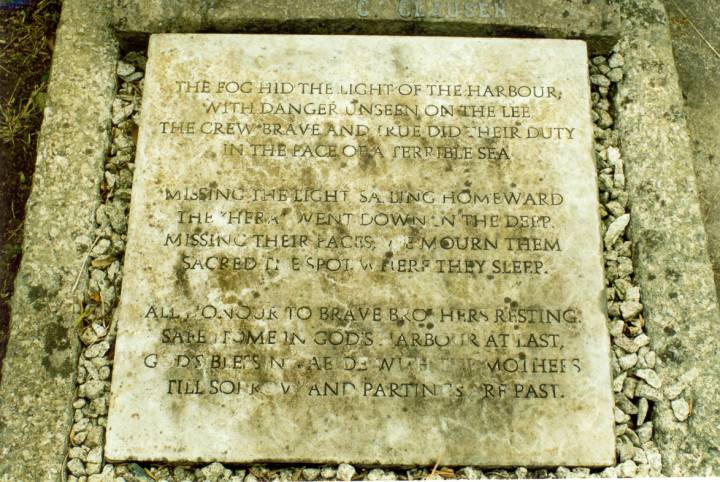

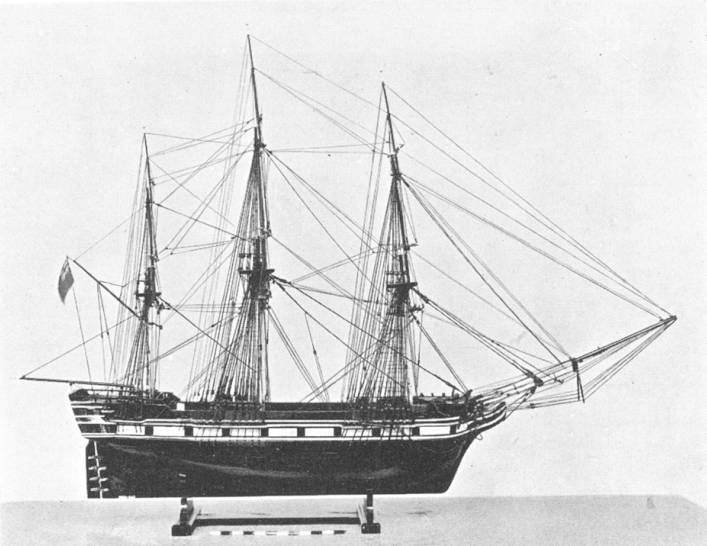

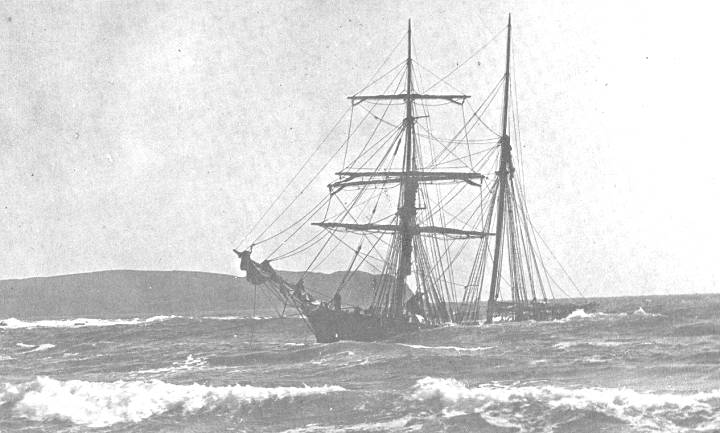

So what happened on that fateful night so many years ago? The northern belle was en-route from New York to London when it encountered a fierce blizzard that drove it partially on to rocks off the coast of Kent. The twenty eight men on board set the anchor to stop the ship from completely foundering, said their prayers, and waited for rescue. In the early hours of the morning three luggers from Margate, Ocean, Eclipse and Victory arrived on site and soon Ocean managed to get five men on board the sailing ship to help with the salvage, and make sure that the ship did not go further up onto the shore. Unfortunately the weather was worsening all the time. The wind was now a screaming gale, mixed with hail sleet and snow. Soon the anchors dragged, and the Northern Belle found herself completely stuck on the rocks with the crew in a very perilous situation.

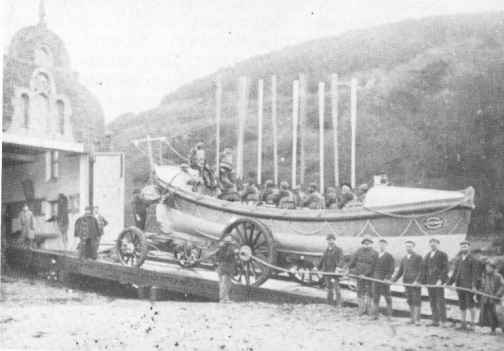

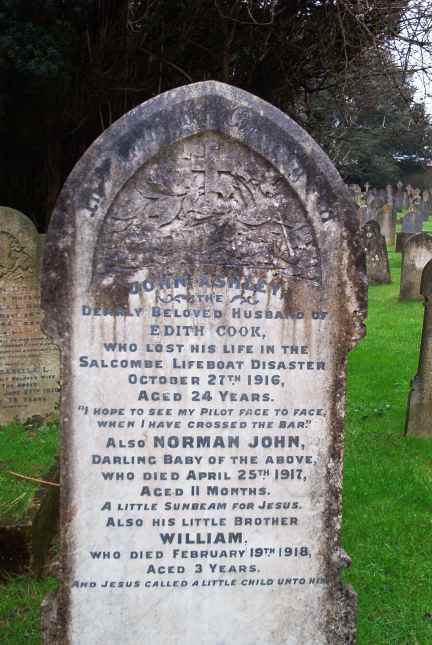

The Ocean closed the wreck and managed to take off five of the crew, but the Victory was completely swamped by the heavy seas and disappeared, drowning all nine of its crew. The Ocean and Eclipse could do no more, so the crew of the Northern Belle had to stay where they were for the night, lashed to the rigging of the only mast left standing. Because of the wind direction, the lifeboats at Broadstairs a few miles down the coast, could not be launched, so they were hitched up to teams of horses and dragged two miles over the hills to a place where they could be launched in daylight. When dawn broke the lifeboats, ‘Mary White’ and Culmer White managed to make three trips between them, taking off all of the Northern belles crew and the men that Ocean had put aboard. One of the lifeboat men, George Emptage, made three trips to the stricken vessel, in part to persuade the Captain to leave. He was all for going down with his ship, but was eventually talked out of it.

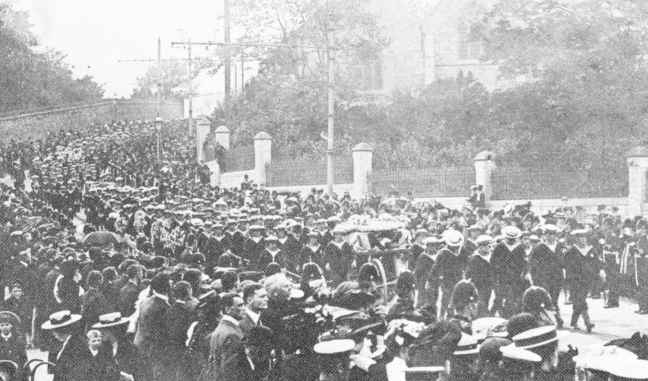

The whole rescue was watched by huge crowds from Margate and Broadstairs who gathered on the beach and cliff tops, some no doubt the relatives of the men lost on the Victory. When everybody was safely ashore, the Second mate was heard to declare that ‘none but Englishmen would have come to our rescue on such a night as this’.

The United States Consul in London launched an appeal to raise funds for the widows and more than 40 children of the nine men who had drowned when the lugger Victory was swamped. Each family received money plus a bible, with the cover embossed with the details of the disaster.