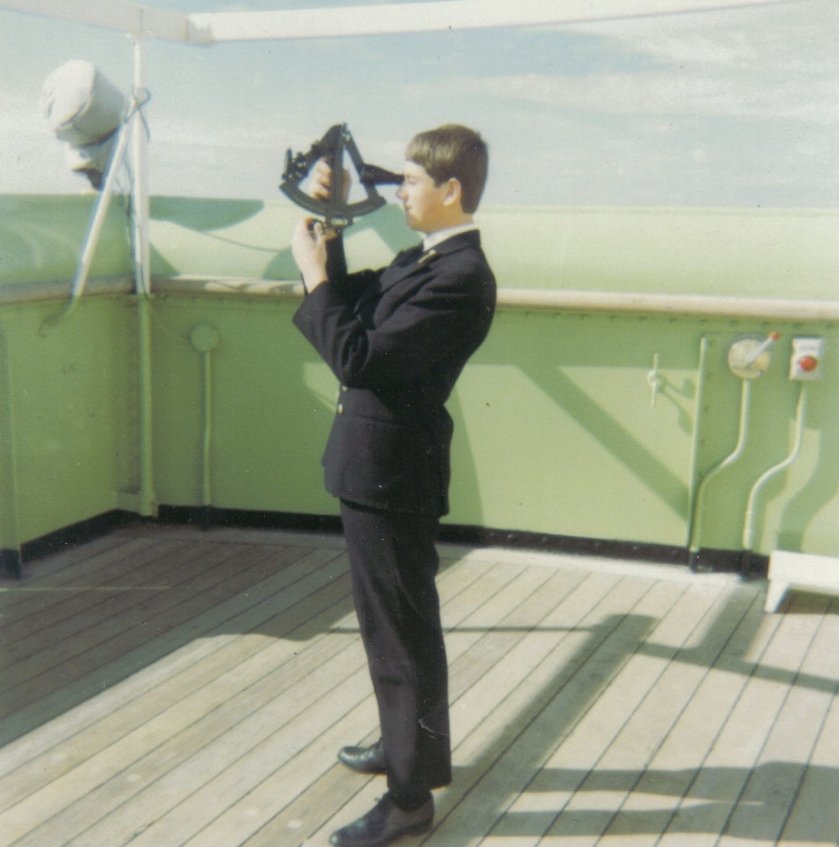

Well over fifty years ago I learned how to dive. It was the time that Hans Hass was making his inspirational TV films, closely followed by Cousteau who truly showed everybody the wonders of the undersea world. Cousteau became for a while obsessed with living underwater, convinced that ‘Inner Space’ was the way forward for mankind. His underwater houses, Conshelf 1 and Conshelf 2 inspired projects all over the world with probably the largest, Sealab being American. Britain was not left out and made its own modest contribution with Project Glaucus, an entirely amateur effort (in the best sense of the word).

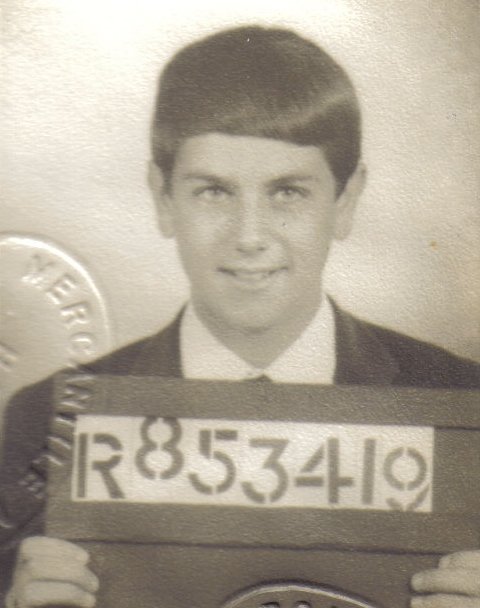

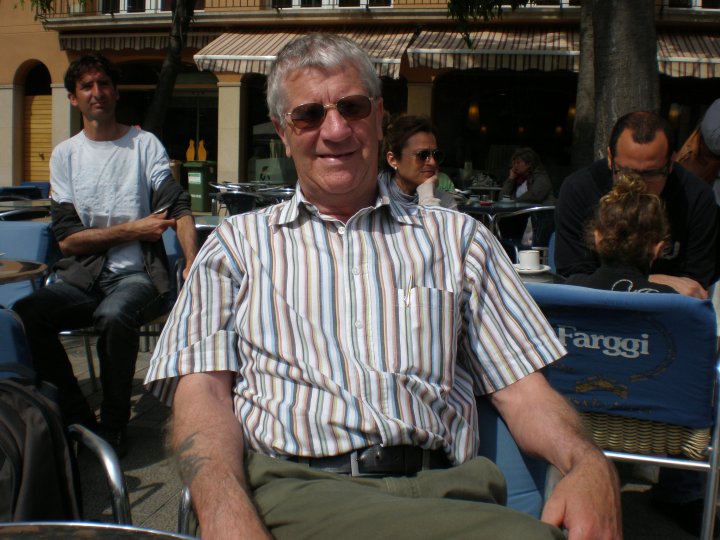

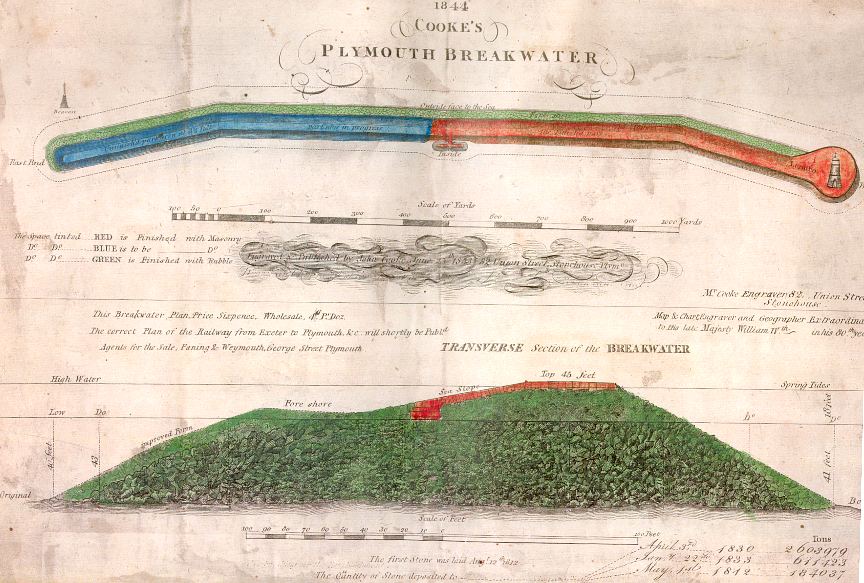

Whilst the Sealab and Conshelf projects had huge budgets, Glaucus cost was around £2000, but what it achieved was truly remarkable. The project was the brainchild of Colin Iwin, who in 1965 was 19 years old and the Science Officer of the Bournemouth and Poole S.A.C. Inspired by Cousteau, he decided to set up a project to put an undersea habitat in place near the Plymouth’s Breakwater Fort and occupy it for a week, along with fellow club member, John Heath, aged 21.

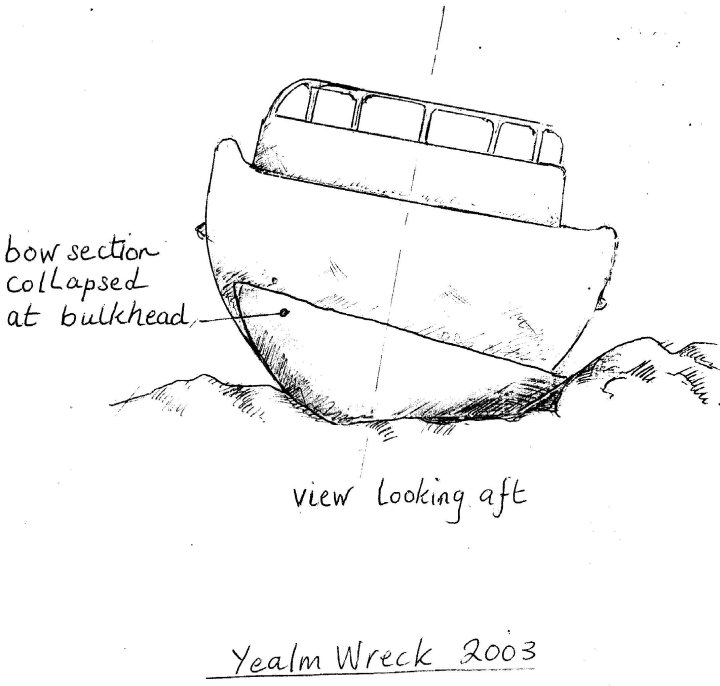

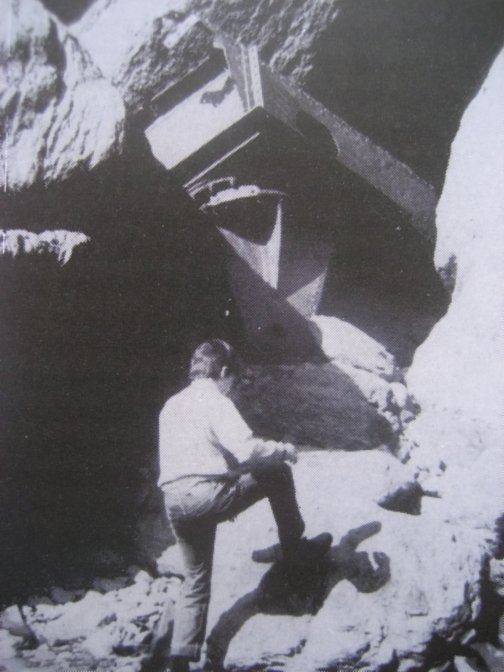

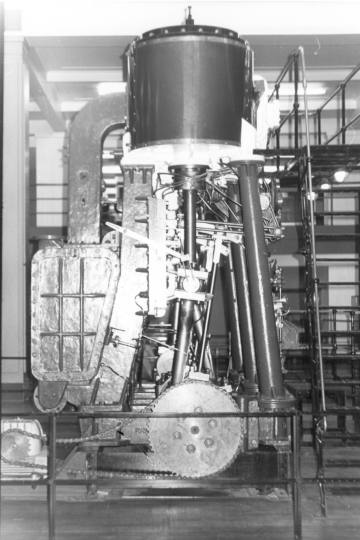

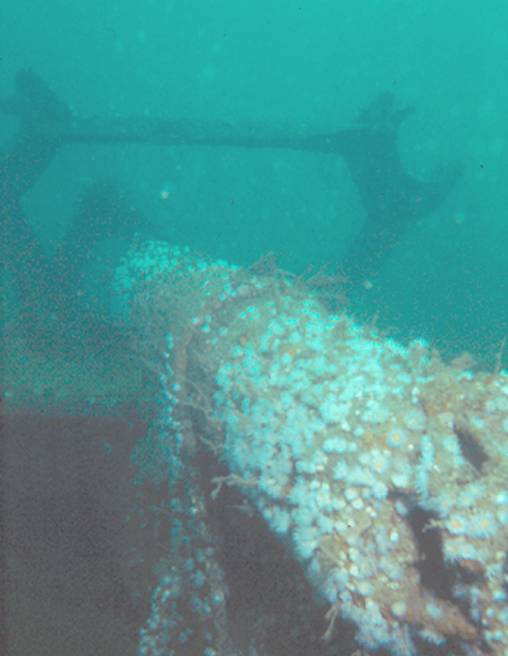

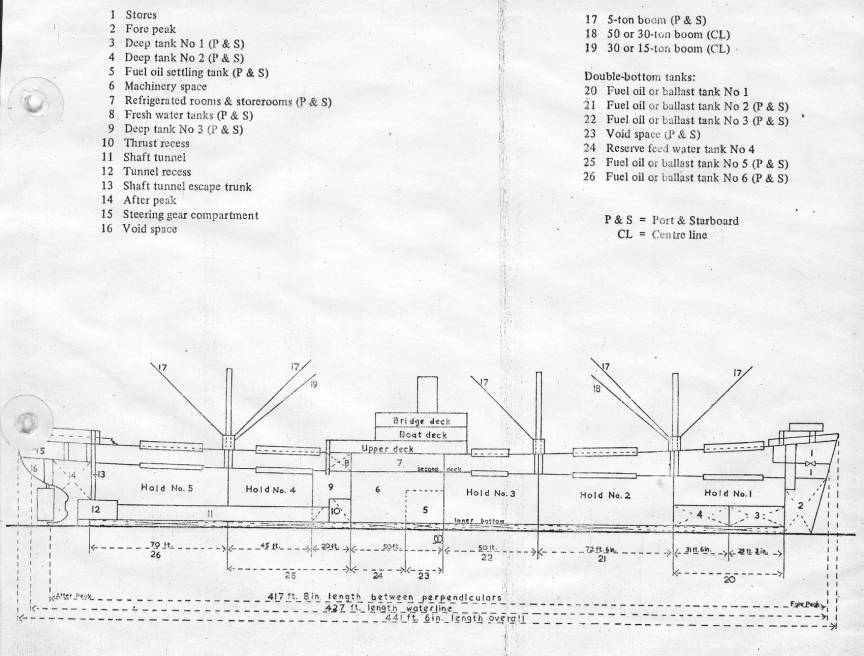

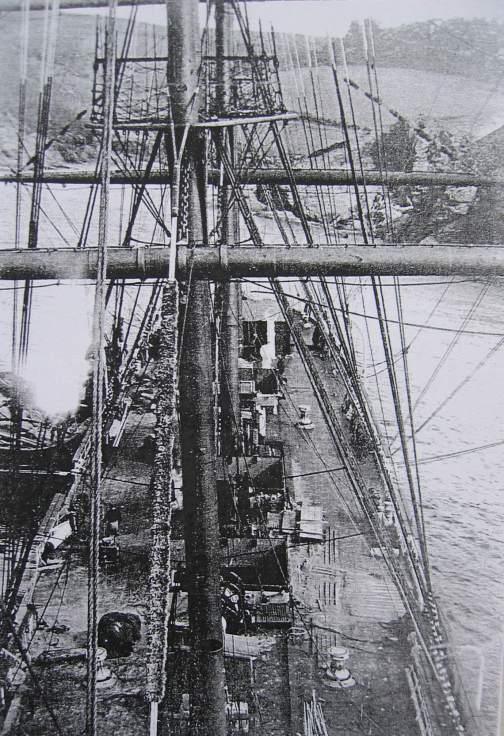

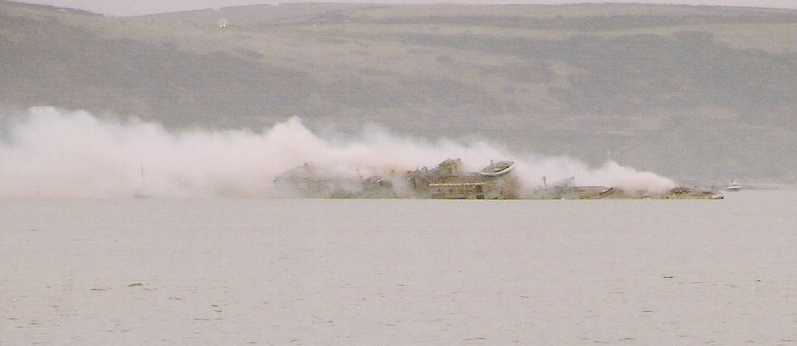

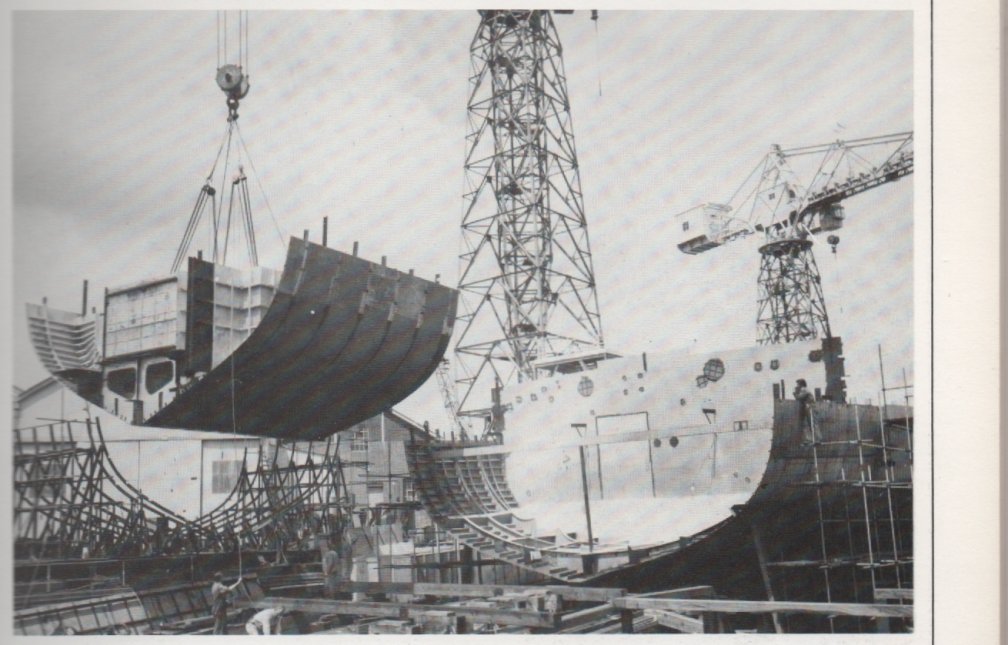

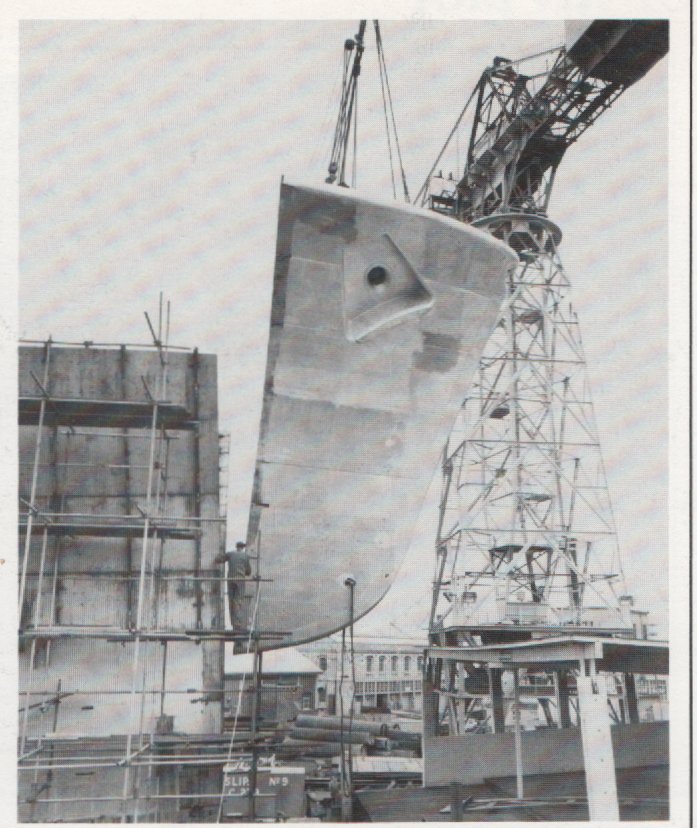

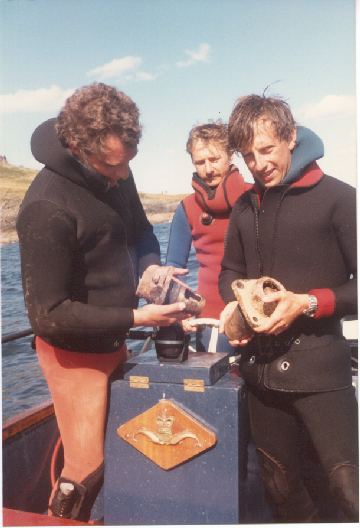

The steel cylinder was built from scratch in a friends boatyard. It weighed two tons, was 3.7 meters long, and 2.1 meters in diameter. The whole structure stood on legs and was ballasted by weight in a tray beneath it. The Cylinder had two compartments, a main living area and separate toilet facilities. Entry was made via a tube fitted to the underneath of the habitat, which was open to the water, thus ensuring that the pressure inside would be the same as the surrounding water resulting in the divers being kept at pressure for the duration of the exercise. Once inside the two men used an old ex army wind up field telephone to keep in touch with their surface team, and there was also an early small CCTV camera to allow the occupants to be constantly monitored.

The big difference between Glaucus and the likes of Conshelf and Sealab, was that the cylinder was completely self sufficient for air. It had no airline but relied on its own artificially maintained environment, with a chemical scrubber to remove the carbon dioxide. It was for this reason that the length of time that the two men spent underwater, still has its place in the Guinness Book of Records.

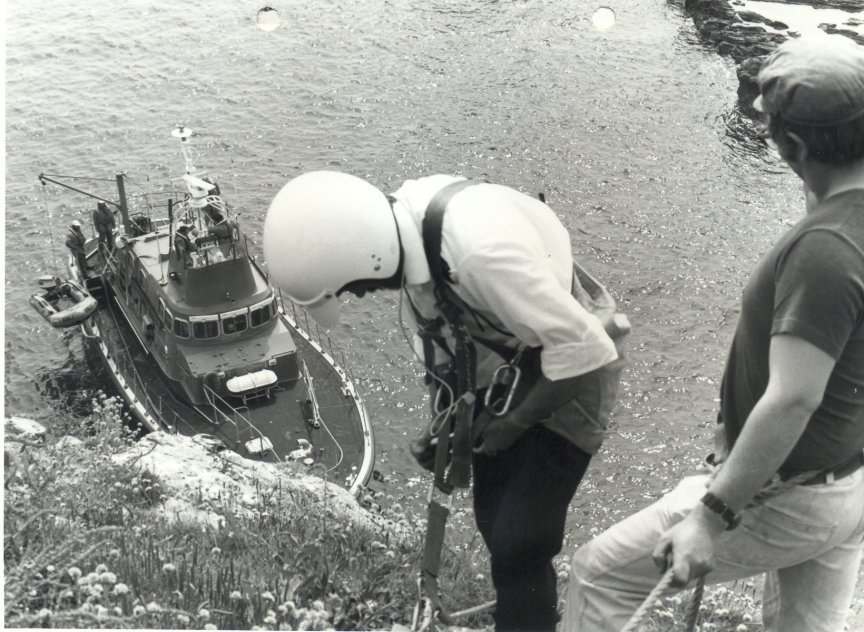

Living conditions in the habitat must have been very rough. The temperature was around 16 degrees with almost 100% humidity. The huge amount of condensation meant that keeping anything dry was nigh on impossible. Food and drink were brought down in army pressure cookers, so even the meals must have been a bit of a disappointment. Even so with all that discomfort, Colin and John determined to continue with the exercise, even venturing outside the cylinder to do a number of surveys to show that divers could not only live at depth, but that they could do some work as well.

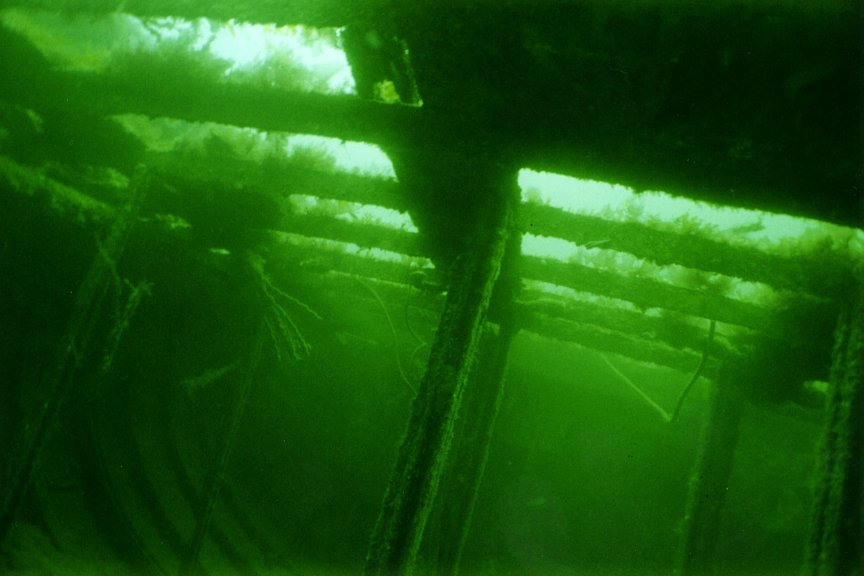

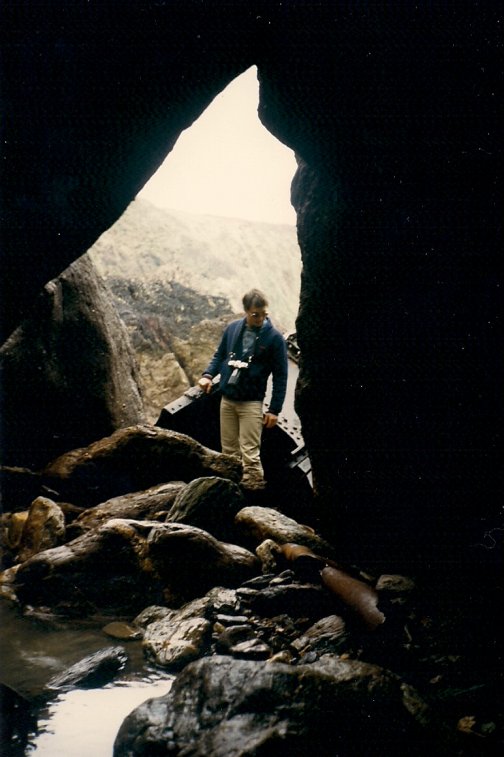

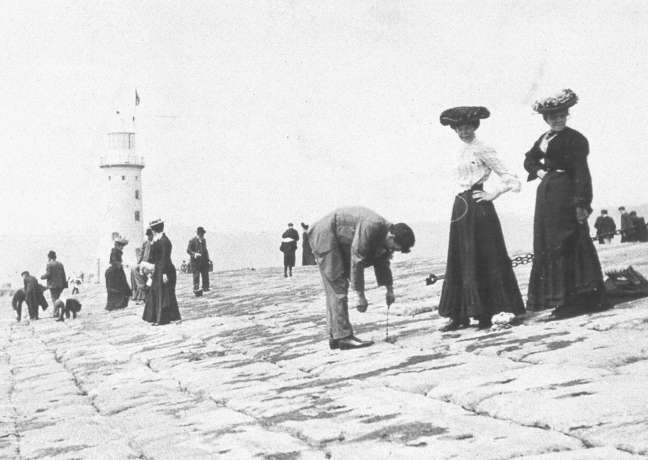

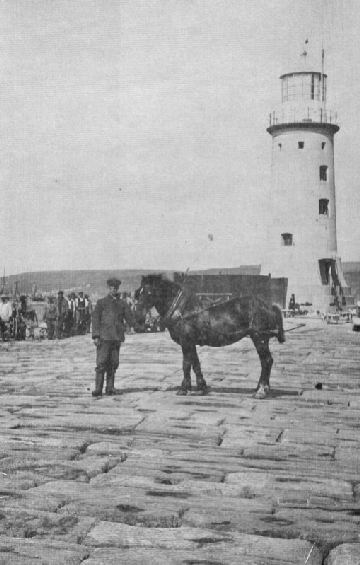

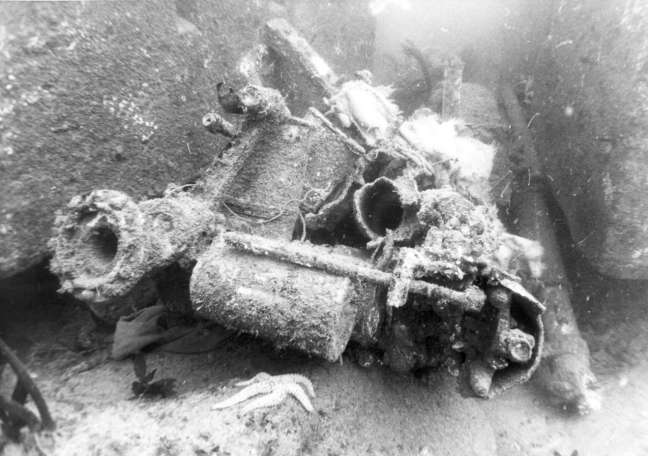

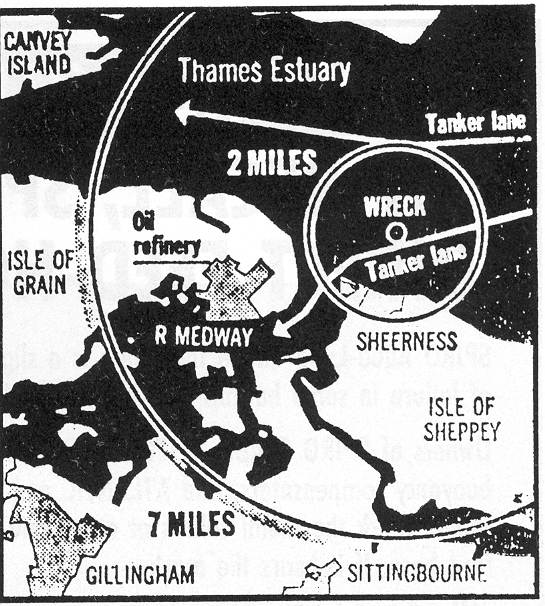

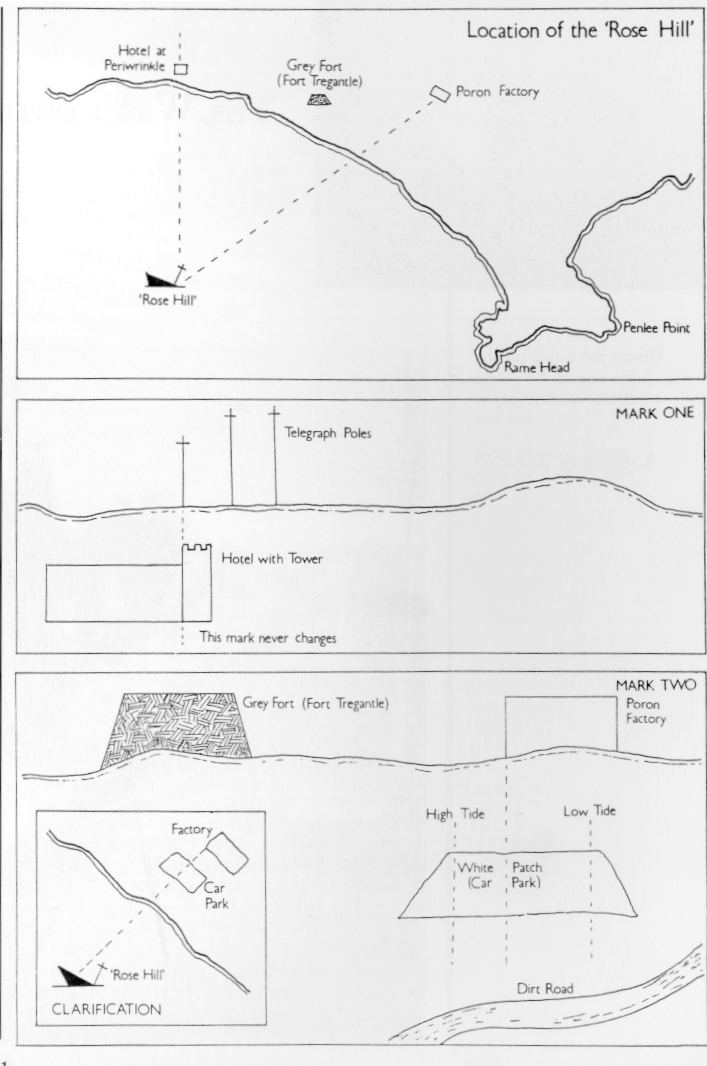

After the seven days were up, efforts to bring the habitat slowly to the surface were abandoned due to buoyancy problems. The two aquanauts made their own way safely to the surface wearing scuba gear. As far as I know nobody else ever did anything comparable, and in a few years everybody abandoned the idea of underwater living as a life changing concept. Today the remains of the Glaucus habitat lie on the seabed close by the Breakwater Fort, not far from where the original experiment was conducted. It is quite easy to find, along with other objects placed on the seabed, to train divers at the now defunct, Fort Bovisand. (see map) because the bottom is silty, the vis is often impaired, but even so it is an interesting dive just to see the Habitat and all the other structures lying around. There is even a cannon to play with. Photographers like the area because it has lots of Jewel Annemones, usually only found much further out.

Years ago I used to do a fair bit of night diving around the Fort (can’t get lost) and found it fascinating with all sorts of small creatures making their homes in the cracks of the huge stone blocks that make up the construction of the Breakwater Fort.

The Glaucus Habitat shows what can be done with a bit of imagination and determination. I am surprised that we all did not make more of it.