The Conqueror is the ship that started it all for me. I had always been interested in shipwrecks, and had already dived on many. But until the Conqueror, I had not really thought about documenting them. In the 70’s and 80’s, Devon and Cornwall seemed to attract an abnormal amount of shipwrecks, and I spent many happy hours climbing precariously down cliffs and scrambling over rocks to examine them.

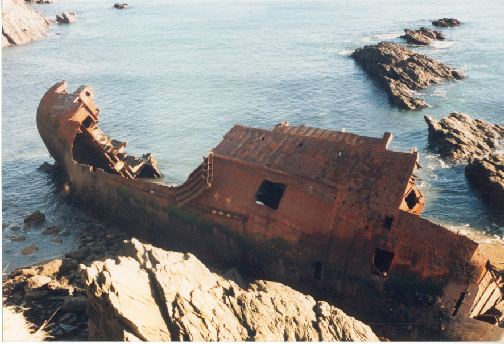

The Conqueror was the first of these wrecks, stranded on the rocks off Penzer Point near Mousehole.

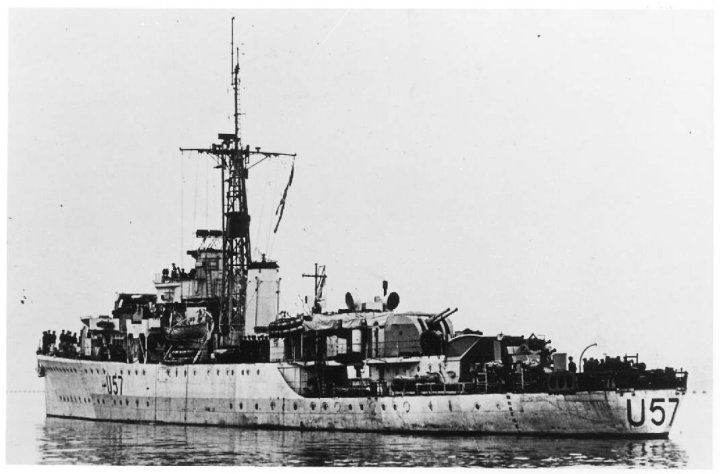

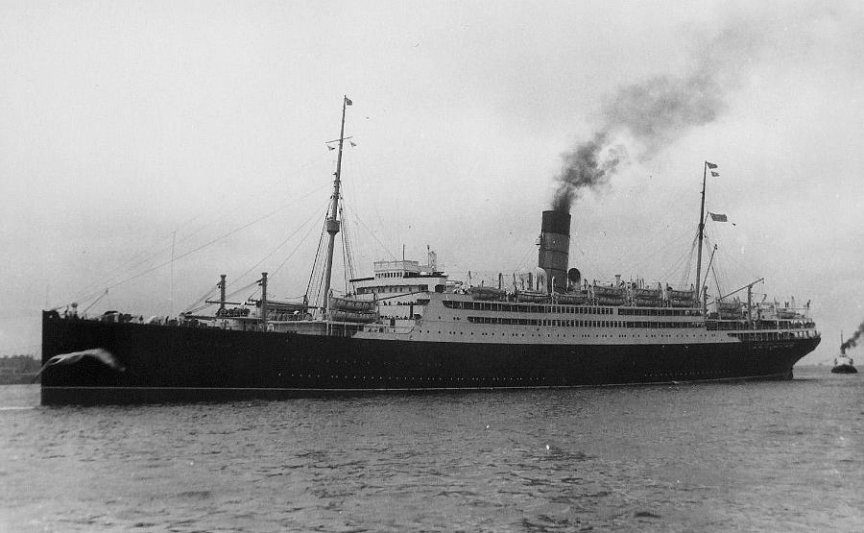

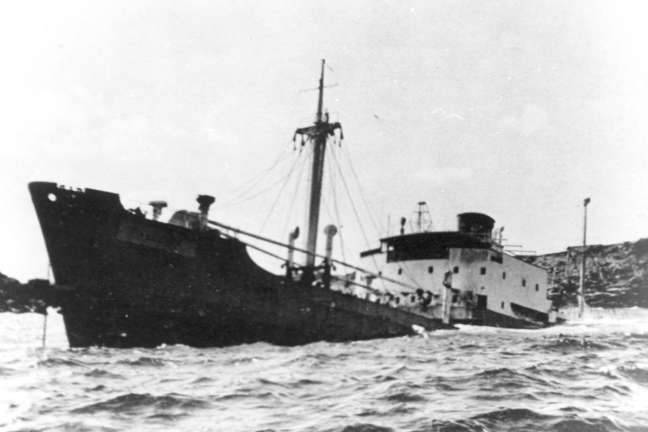

The Conqueror was a modern freezer trawler built by Hall, Russel & Co Ltd in Aberdeen1965, for the Northern Trawlers Company. By 1977 she had undergone a major refit to extend her freezer capacity, and left her home port of Hull to go mackerel fishing in Cornwall. On the 26 December 1977 she was off Penzer Point with 250 tons of mackerel on board when she ran into bad weather, and ran aground on the rocks nearby, in the darkness of the early morning. None of her 27 crew were hurt or injured and it was something of a mystery why the wrecking took place, as although the winds were blowing force eight, the sea was relatively calm. In any event the Penlee lifeboat was called and swiftly took of most of the crew to nearby Newlyn, leaving the skipper, Charles Thresh, and three others on board to see if they could help refloat her. By now the engineering steering flat and the tunnel to the engine room was full of water, with the stern firmly aground on the rocks.

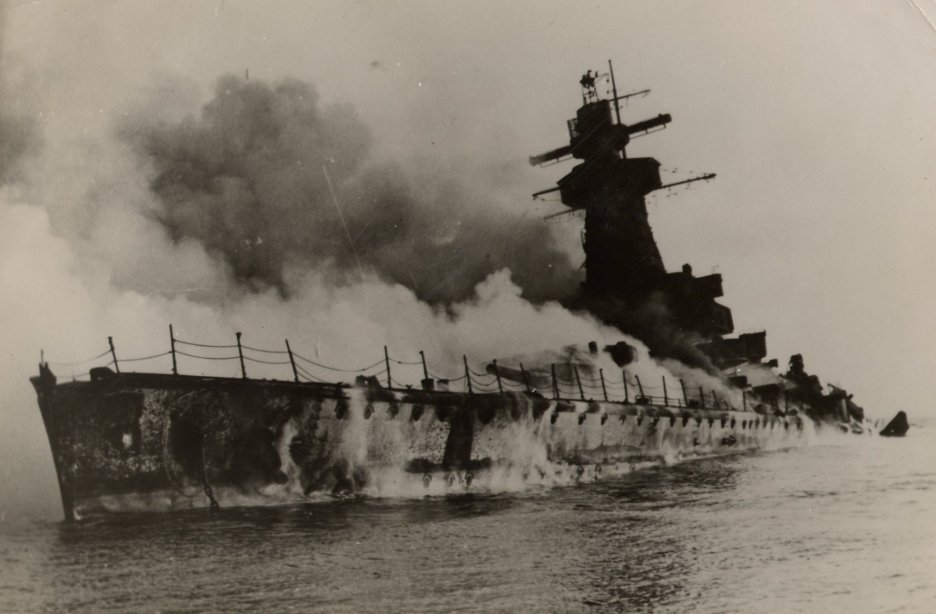

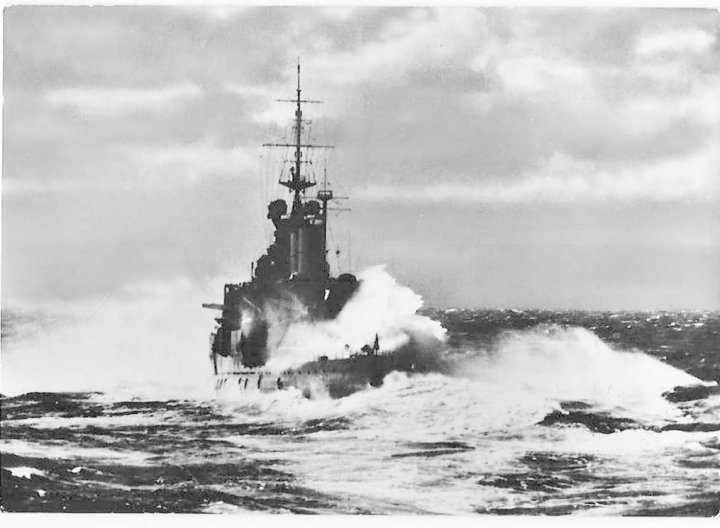

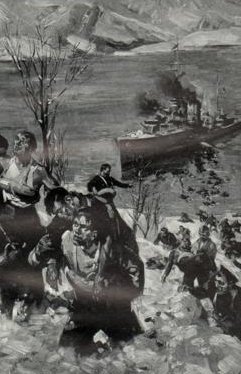

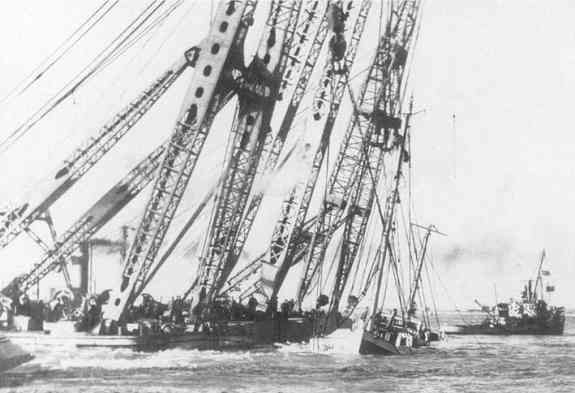

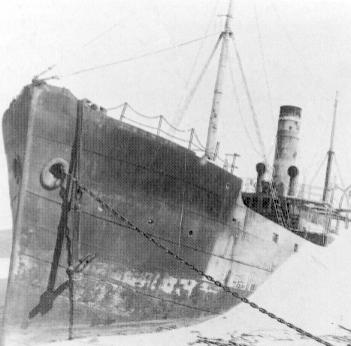

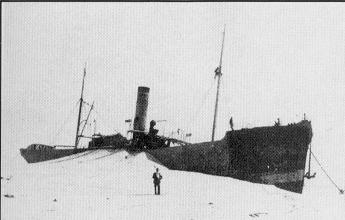

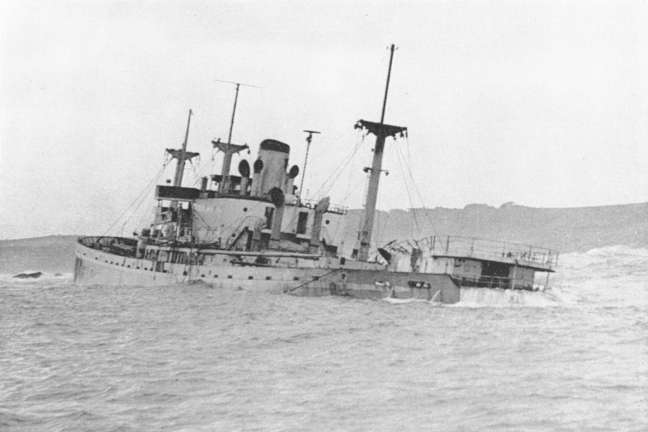

The Trinity House vessel Stella, and the trawlers Farnella and Junella stood by the stricken vessel until the salvage tug Biscay Sky turned up with some huge water pumps. Meanwhile the skipper and his mates had tried to patch some of the worst holes and got the pumps working. The salvage team continued the hard work, and were within a couple of days of being ready to pull her off, when the weather turned nasty again. A sudden gale blew up, and left the Conqueror with a 45 degree list, and submerged from the stern to midships. On the 21 January 1978 the salvage divers reported that she was now too badly holed to get off, so they packed up their gear and the Conqueror was abandoned to the sea.

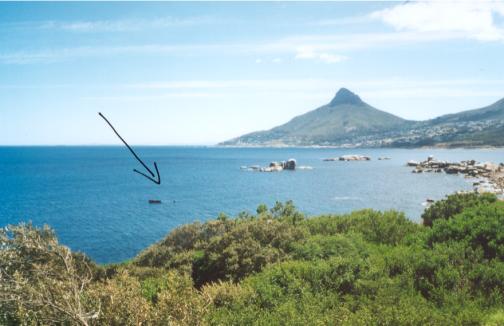

It was a few days after she had been abandoned that I went to see her for myself. If you look closely at the photos, you will see a rope ladder hanging from the bow. I scrambled up that with my mate, and together we made our way towards part of the engine room. Although the stern was firmly grounded it was still twisting in the waves, and as the tide set in the waves bounced off the stern plates with a noise like a gong. The water right at the stern was pulsing up towards us with every new wave and the deck was slippery with oil. With the whole ship canted over on her starboard side, it was hard to keep our footing. All thought of getting a souvenir disappeared as the water got closer to us. The stern seemed to be twisting even more, and the banging got louder. We slipped and slid back to the rope ladder and thankfully climbed down to the safety of the rocks.

The Conqueror stayed stuck on the rocks for some years before she finally slipped beneath the waves. She became something of a local tourist attraction, so much so, that in the early days the Police had to re- route traffic around Mousehole as it was getting completely grid locked.

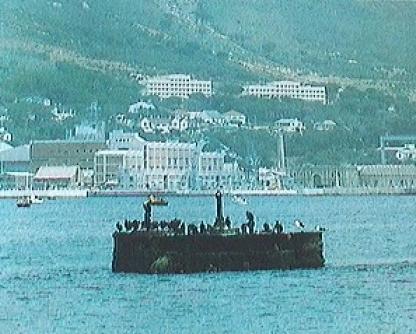

I finally got to dive the wreck in August 1990, so anything I say here will be ancient history. Parts of it must have been quite shallow, as my Logbook states that there was quite a lot of kelp on her, and that she was quite broken up, but in big pieces, and lots of them, with a few nets wrapped around the crane areas. The wreck is lying more or less upright, and the deepest part is in about 20 meters. Vis was about 20 feet, so for the photographer it will be quite interesting.