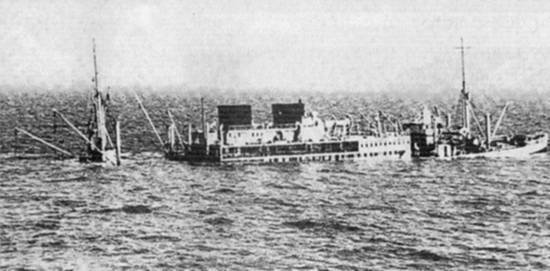

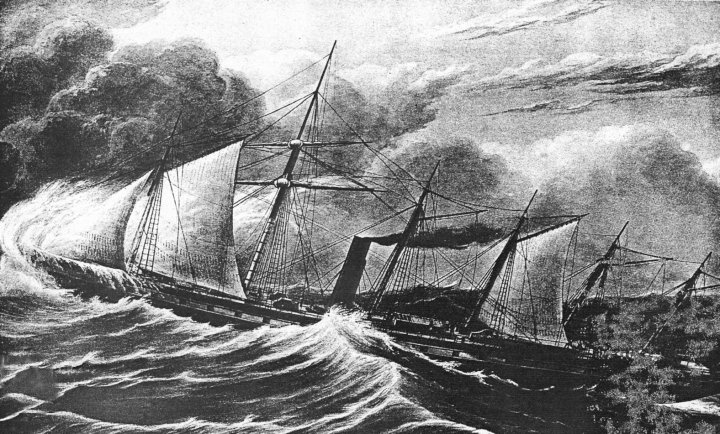

Named after one of the Falkland islands most common penguins, the Gentoo came to the Falklands in 1927 and then spent many years carrying supplies and wool for the farming company Dean Brothers. She later passed into the ownership of Bill Hills until 1981 when she was sold to a new arrival to the islands, who intended to convert her to a houseboat. However when she was put on a new mooring she rested on the bottom and heeled to starboard and the rising tide flooded her.

All I know about the Golden Chance is that she was built in 1900’s and came to the Falkland Islands in the 1940’s for sealing protection.